Shorelines (35 page)

Authors: Chris Marais

Tags: #Shorelines: A Journey along the South African Coast

The metallic titanium (also called ilmenite) in the sand conducts and retains heat and moisture. And if Rio Tinto Zinc’s bid to mine ilmenite here in the early 1990s had been given the go-ahead, this natural turtle incubator would have been destroyed. Eventually, there would be no more summer nocturnal tours to watch these ‘big mamas’ slowly hauling themselves up the beach to lay eggs.

But the potential loss of turtles was not the reason that eventually swayed politicians to reject mining in favour of retaining natural beauty in the mid-1990s. Nor was it St Lucia’s extraordinary ‘sense of place’, invoked by environmentalists who energetically opposed mining because it would destroy a fragile beauty and biodiversity unparalleled in South Africa.

It wasn’t even because legendary conservationist Dr Ian Player threatened to lie down naked in front of the bulldozers.

The real reason was sustainable jobs. Ecotourism promised to employ three times more people directly and thousands more indirectly, compared with dune mining, which offered only 313 lifetime jobs.

Titanium mining is hugely profitable for the mining company concerned. Valued at $1 200 an ounce (in 2006), it’s more precious than platinum – and easy to mine. You just scoop up the dunes, sift them and rebuild them on the other side. That’s the theory, at least. In practice, the ilmenite also lends the dunes structure and strength, which is why they are some of the highest and most ancient beach dunes in the world. Once mined, they often slump. And no one can recreate their generous biodiversity. And then, obviously, the turtles will go elsewhere for an easier lay.

Kian’s second love – loggerheads – are far smaller at about 120 kg. While leatherbacks use a wide variety of nesting sites to lay eggs, loggerheads are a less adventurous lot. They will favour specific sites, adding a few ‘wild-card’ nests just in case of tsunamis, fires, hurricanes and predators.

“They’ve got iron particles in their heads, which become magnetised while developing in the soft warm maternal sands of St Lucia,” says Kian. “So they can accurately locate the birthing area. It’s a type of magnetic memory that apparently kicks in when the females are ready to lay, effectively guiding them back to their original birth ground.”

On our way to the beach, we pick up some foreign tourists. One Aussie guy wants to know: is it true that wild animals roam the streets of St Lucia at night?

“Oh yes,” Kian says, his tone serious. “There are at least three leopards that regularly come into town. Jack Russell terriers don’t live much beyond 18 months around here before they get eaten. That’s why we call them Chinese takeaways.

“And there are hippos that occasionally come to town, especially when it’s dry, like now. They keep the lawns in the public areas down to a decent trim. And when it floods, crocodiles have been found in the swimming pool of a local resort.

“Just over 18 months ago a herd of elephants walked into St Lucia after chasing a stroppy young bull. A helicopter had to be called in to get them back into the park.”

By now, there is silence in the vehicle. The urge to insert a loud feline yowl or elephantine trumpet is almost unbearable – and yet I, in an amazing display of maturity, shut the hell up.

Then we come across (and wake) a pygmy kingfisher on a thin branch, being whipped by the night wind.

“Meet the most photographed pygmy kingfisher in the world,” says Kian. The bird opens one eye, favours each of us with a glare and goes back to sleep.

The drive is full of these encounters and little factoid bytes from Kian. At Cape Vidal we eat a late meal of spare ribs, samoosas and salad. It’s 10.30 pm and we’re only expecting our first turtle well after midnight. Kian drives onto the beach and turns north along the high-water mark, the surf nipping at our wheels. A scant 50 metres on, our guide gasps:

“I can’t believe it.”

He points at fresh loggerhead tracks. This old turtle is heading for a spot just below the normally packed carpark, where the ocean roar is often smothered by loud music. Tonight, there is no sound beyond that of the waves.

Kian keeps us all at bay until the turtle has gone into an ‘egg trance’ and our presence matters no longer.

“I call it a genetic epidural,” says Kian. “Nature just switches off the senses and instinct takes over. Everything slows down. It’s a bit like an old Windows 92 program. Once a certain action (such as digging) ends, there’s a couple of minutes’ break, and then the next one (in this case, egg laying) starts. Always the same – and always very slow and methodical.”

We kneel in reverence behind the loggerhead mother. It is a perfect night, with only a slight sea breeze. Here before us is a seaborne creature the size of a modest coffee table, digging a hole in the earth for her eggs, her flippers flicking sand away in a 200-million-year-old ritual.

Kian whispers his praises for her choice of egg-laying spot.

“This is a very successful place. It’s not too close to the forest, so the hatchlings have a good chance of reaching the sea without being too exhausted. But it’s also far enough up so as not to be disturbed by beach walkers and high-tidal waters that could swamp the nest.”

The eggs begin to pop out in quick succession. The mom is finished. You can see it costs a turtle an enormous amount of energy to crawl out of the buoyant sea, submit to exhausting gravity, and dig a careful hole for her babies.

As we drive away, we see the waiting ghost crabs skittering away in the headlights. In a few months, the tiny turtle babies will have to run the gauntlet of these ravenous creatures, pale death riding on eight hydraulically operated legs.

“Just a warning here,” says Kian. “If you ever come across a nest of hatchlings as they emerge, never pick them up and carry them off to the surf. They need the distance between nest and waves to open their lungs and coordinate their limbs. If you interfere, they’ll just drown.”

The rest of the night drive along the beach reveals wonders such as a long-dead melon-headed whale, a live crocodile that runs off into the surf and rides the breakers, a distant shadow of a hunting leopard and a dehydrated python that allows Kian to lift and display him to his guests. The snake has been destined to be the leopard’s late supper, Kian reckons. To give it a better chance, he ascends the closest dune in darkness to deposit it gently on the dune floor.

“Are you walking across the lake tomorrow?” he asks Jules later, just before dropping us off. She nods.

“Watch out for the Mpate Monster,” says Kian ominously, with laughter somewhere behind those intense eyes.

“What’s that?”

“It’s a 7-metre-long crocodile that lives somewhere in the lake,” he says. I can see that as a young boy he loved putting spiders in girls’ lunch boxes. But then, who didn’t?

“During World War II, the Catalina pilots would strafe the larger crocs as they flew over them. It was good gunnery practice. But they never got the Mpate Monster.”

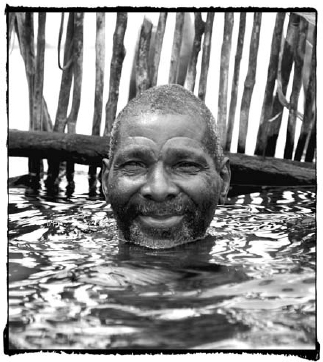

The next day we crossed the utterly dry plains of Lake St Lucia with a group of Bhangazi elders, including Ephraim Mfeka.

“As little boys, we used to wade across the lake from the eastern shores to a trading store on the other side,” he said. “But now, just look at this drought.” We were in an open plain that was once lake, speckled with small, white, crustacean shells. Only little clumps of grass survived here now.

If the Mpate Monster was indeed in the neighbourhood, he was no doubt in lurk mode until the next bout of good rains fell over Lake St Lucia.

Ephraim told us how his clan would shout and sing and beat the water in the crossing to frighten off gathering crocodiles. But they were not always successful.

“My mother was taken by a crocodile,” said Ephraim. “We went out and killed that one.”

This was the first time the elders had crossed the lake in more than 40 years. In the mid-1950s the apartheid government began forcibly removing thousands of people from the eastern shores of Lake St Lucia in order to plant what the bitter Bhangazi community would later refer to as “soldier trees” – a parade ground of pines and gums.

“They removed us in trucks. It was up to the driver where to drop us,” said Ephraim. “If he liked a certain hill or a tree, that’s where he would take us.”

When democracy came and their land claim was deemed successful, the Bhangazi clan opted for a cash payout instead of occupation. They still retained the right to develop a small peninsula for a lodge and heritage centre. After much negotiation the cash payment worked out at R30 000 per household.

“The money,” said Ephraim, “has been a curse. Families were fighting over it. One man bought a car with his money. Then he had an argument with his son, who stole it and later wrecked it. Others died before they could use their share, and their children fought over the spoils.”

“If I had known then what I know now,” said Ephraim. “I would have invested in a tourism thing. Maybe a camp with luxury tents.”

Many of the people dispossessed in the 1960s and 1970s went to live in the Dukuduku Forest outside the town of St Lucia. They dug their heels in here and refused to be budged. Jules and I met four Dukuduku Forest people the next day who had also embraced the Rastafarian faith.

“Just call me Phungula,” said BA (Bhekinkosi) Phungula, the leader of the Manukelana Art and Nursery project. He had dreadlocks and a guileless smile.

Five years before, Phungula and his group decided to start a plant nursery. A local chief gave them land.

“For funding, I suppose we could have asked the municipality for millions,” said Phungula. “But we didn’t. Instead, we asked everybody for their leftover things, whatever they really didn’t need.”

So they ended up with old tyres (plant containers), drums, plastic bags, shade netting, assorted pipes and planks from the sawmill down the road. Phungula showed us an array of seedlings that included Natal gardenias, jacket plums, coastal coral trees and flat tops. We walked past a place called The Alex Frisby Tower.

“Last year, a group of students from England visited us and wanted to know what we needed most,” said Phungula. “Of course, we said we had a water crisis.”

So the group returned and spent two weeks setting up a raised water tank and establishing a vegetable garden for the project. The only one of the English friends who couldn’t make the trip was someone called Alex Frisby. But he ended up being here anyway, if only in name.

“We never thought that people from the other side of the world could mix concrete and push wheelbarrows,” said Phungula. “It gave us so much hope. We knew we were doing something good.”

The water pipeline between Mtubatuba and St Lucia flowed right past them on the other side of the road, but their application to tap into it looked as though it would take another five years to be considered. So now they were drawing from the ever-dropping water table with a foot pump.

What did the project name, Manukelana, refer to?

“It’s the name of one of the old regiments loyal to King Cetswayo,” said Phungula. “It also means ‘sixth sense’ – the one that makes you know by instinct.

“Our lives depend on plants. If a woman is breast-feeding, she might need a certain herb. In our culture, if a woman is anxious, she must go to the marula and chew on the bark. While she has the bark in her mouth, she must speak out about everything that is worrying her. She must tell it to the tree. Then she must spit out the remains of the bark and put it back in the tree. And she must cry until she feels better.”

The project also supplied the local healers with medicinal plants. A famous and powerful healer in the St Lucia area known as Mkhize brought them valuable seeds for planting.

“Especially the pepper bark,” said Phungula. “It is very good for clearing chest infections.”

Phungula and his friends all came from families that had snuck into the Dukuduku Forest in the 1970s and remained.

“Now, if you take us out of the forest, it is like taking a fish out of the water,” he said.

Their forest home had morphed into a settlement called Khula Village and had become a real political hot potato. What constituted destruction? Was it a man making a small garden for sweet potatoes, maize and cassavas? Was it someone who cleared wild land and planted a sugar-cane empire? Much of this province was a vast swathe of waving green.

What used to be simple thatching grass in old New Guinea was eventually found to taste sweet. The sugar-cane craze spread through China, India and the Mediterranean. The Crusaders brought it back to England and then it became the main Caribbean crop. And a modern-day obesity curse, not to mention the major reason my upper right molar now carried a stiff bolt of very expensive titanium that was, thankfully, not ripped out from under a couple of loggerhead eggs …

St Lucia to Kosi Bay

His childhood name was

Skebenga

(mischievous one). If his wife Tracy weren’t around to keep an eagle eye on what he ate, his basic diet would consist of copious cups of sweet milky tea, crisps, bread and apricot jam, with a stiff Jameson’s in a tin mug to end the day.

His ideal mode of dress is a khaki shirt and a sarong worn with rough-tread sandals. Whenever he comes across a piece of water he has a very strong urge simply to fall into it.