Shakespeare's Kitchen (23 page)

Read Shakespeare's Kitchen Online

Authors: Francine Segan

Feasts with fifty or more separate dishes were common for special events, but guests were not expected to try all fifty dishes. The assortment of dishes was presented so that each person could find something he or she liked. In 1617, Frayn Moryson, a travel writer, wrote of this English custom, “The English tables are not furnished with many dishes, all for one mans diet, but severaly for many mens appetite, … that each may take what hee likes.”

Following are highlights of how people entertained in Shakespeare’s day with hints on how to give Shakespeare-themed dinners, buffets, and parties.

CASTING CALL

.....

… FIND THOSE PERSONS OUT

WHOSE NAMES ARE WRITTEN THERE, AND TO THEM SAY,

MY HOUSE AND WELCOME ON THEIR PLEASURE STAY.

Romeo and Juliet, 1.2

AS THERE WAS NO MAIL SYSTEM IN SHAKESPEARE’S DAY, MESSENGERS WERE SENT TO

personally invite each guest to a feast.

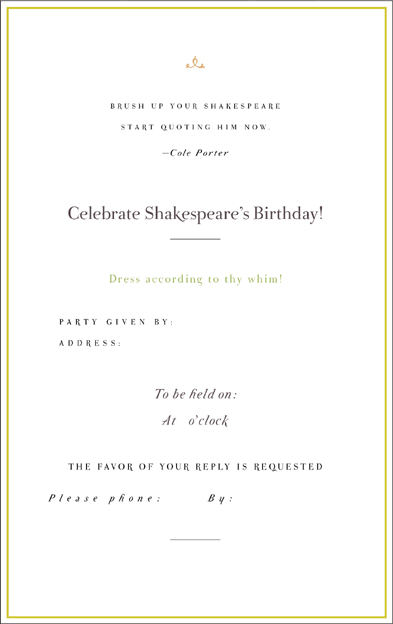

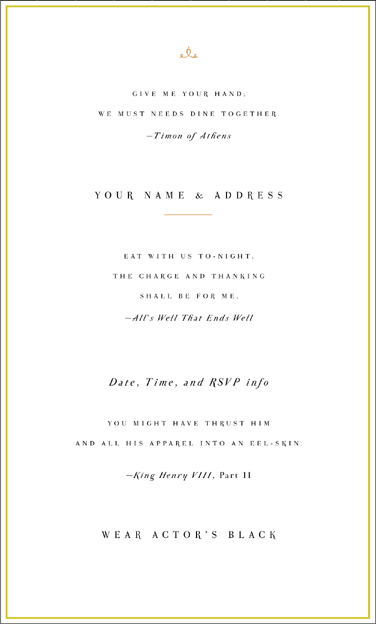

For your own modern feast you might like to copy one of the following sample invitations. You can re-create them in calligraphy or on a computer. Staining the paper with tea or burning its edges adds a theatrical aged effect. Closing the invitation envelope with sealing wax is another nice Elizabethan touch. Seals with initials and sealing wax can be purchased at fine stationery stores.

Invitation No. 1

Invitation No. 2

Invitation No. 3

SEATING

.....

DURING THE CLASSICAL PERIOD, IT WAS BELIEVED IDEAL FOR A PARTY TO INCLUDE

no fewer than three guests, the number of the Graces, and no more than twelve, equaling the Muses. Although the Greek ideal was known in Shakespeare’s time, Renaissance dinners often included many more guests. Large feasts got so out of hand that in Italy special laws were enacted that specified the number of guests allowed based on the host’s social rank.

Seating was very carefully orchestrated in Shakespeare’s day with the hierarchy for table placement of a duke, marquese, earl, bishop, viscount, baron, or knight well defined. A page would escort each diner to his or her place based on a printed master seating list. All seating was assigned by social position and rank.

For your own feast, you might make place cards from color copies of sixteenth- or seventeenth-century paintings. Or use postcards of paintings, which are available at most museum gift shops. Scrolls made from parchmentlike stationery can also serve as place cards. Each scroll can include a different Shakespeare quotation or historical food fact for your guest to read aloud.

Knowing whom to invite and, even more important, where to seat the guests you have invited is often the key difference between a wonderfully noisy and chatty dinner party and an average gathering.

To stimulate conversation, seat couples and friends who know each other well at opposite ends of the table. Place people with similar hobbies, not necessarily similar occupations, near each other. For example, rather than seating two attorneys together, place the mountain-biking litigator near the artist who hikes.

In planning your guest list don’t shy away from including someone you just met. What better way to get acquainted than in your own home with a group of your friends? Even if it turns out that you don’t have anything in common, one of your other friends might. Consider including a relative on your dinner-party guest list. It is often pleasantly surprising how different someone can be away from the rest of the clan.

SCENERY AND PROPS

.....

LIGHTING

The sun, firelight, and candles were the only sources of illumination in Elizabethan England. A room lit by candles is dramatic for a modern party. Beeswax candles have a lovely glow and add a pleasant fragrance to the room.

LINENS AND TABLEWARE

As guests entered the dining hall, they washed their hands in scented and flowered water provided by the host. Guests would find very large, plain white cloth napkins at their places to use during dinner and to wrap leftovers to take home. Women were expected to place the napkin on their lap, men to tie it over the left shoulder or over their left arm.

In

Murrells Two Books of Cookerie and Carving,

the butler or pantler is advised to “lay the cloths, wipe the boorde cleane … then set your Salt on the right side where your Soveraigne shall sit.”

Judging from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century paintings of feasts, tablecloths were almost always white. It remained the typical color for table coverings until the end of the Victorian era. If you prefer to create a more fanciful setting, use the colors popular then: gold, burgundy, and royal blue. A velvet cloth, a tapestry, or even a Chinese rug might be a possible table covering for your modern Elizabethan party.

Costly china and ceramic plates and dishes were not yet common in Shakespeare’s day and instead wooden, pewter, or silver plates were used.

I DRINK TO TH’ GENERAL JOY O’ TH’ WHOLE TABLE …

MACBETH, 3.4

Raising one’s glass to the health of another guest, especially of an esteemed lady at the table, was common in Elizabethan England, and various etiquette books suggested apt sayings. Pieces of toast have been added to drinks since the Middle Ages to improve the beverages’ flavor, and it is from that practice that we derive the expression “to drink a toast.”

Drinking goblets were made of wood, pewter, leather, or silver. Servants would bring a drink when asked, and the glass would then be rinsed in a communal basin and used for the next person.

For authenticity, you might explain this custom to guests and leave the glasses on a sideboard so they can replenish their own drinks during the party.

TABLE DÉCOR

In Shakespeare’s day the dessert table was decorated with sculpted walnuts, tiny baskets, or miniature fruits and animals all made of marzipan or marchpane, as that sweet almond paste was then called. You can give your guests small jars of marzipan and invite them to create their own Elizabethan treats. You might discover hidden artistic talents as you see how much fun adults can have playing with their food!

While flowers were not generally set out onto an Elizabethan table, there is no reason you cannot include flowers at your feast. Taking a stroll through an art museum or leafing through books on still-life painting of the era can inspire your floral arrangements.

REFRESHMENTS

.....

Kitchens were far away from the dining halls and food was, by necessity, served at room temperature. Many gourmets today prefer food at room temperature and suggest that it improves flavor. Serving all foods at room temperature certainly reduces a host’s anxiety, as the food can be prepared before guests arrive.

Most of the recipes in

Shakespeare’s Kitchen

can be prepared just prior to your party and are delicious eaten at room temperature.

“The English Husbandmen eate Barley and Rye browne bread, and preferred it to white bread abiding longer in the stomack … but Citizens and Gentlemen eate most pure white bred.” Written in 1617 by John Murrell, this quote aptly differentiates the classes by dining customs. Farmers and laborers needed the more filling, slow-burning calories of hearty dark breads, while the upper classes ate lighter white bread. White bread was made much as we make it today, with flour, water, salt, and yeast.

In the Middle Ages the top slice of a loaf of bread was served to the most esteemed guest at the table. It is from this practice that we get the expression “upper crust,” meaning the elite. By Shakespeare’s time it was considered elegant to serve only individual small rolls to diners.

SHE WAS FALSE AS WATER

.

Othello, 5.2

Water in Shakespeare’s England was not reliably safe to drink and even the word

water

was often symbolic of falseness and lies.

According to health author Andrewe Boorde, writing in 1542, water is “unwholesome taken by itself, for Englishmen.”

So, for strict authenticity, do not allow your guests to drink a drop of water! Ply them instead with fruit cider, hard cider, ale, beer, sherry, and, of course, red and white wines, which were considered essential to digestion.

CURTAIN CALL

.....

ENTERTAINMENTS

THOSE PALATES …

MUST HAVE INVENTIONS TO DELIGHT THE TASTE …

Pericles, 1.4

Hosts have welcomed guests into their homes for centuries. Every good host, but especially the Elizabethan host, tried to delight and entertain guests with special foods and surprises of all sorts. Thomas Hill, in his 1567 book,

Naturall and Artificiall Conclusions,

explained “how to make an egg fly about, a merry conclusion,” by putting a flying bat into an emptied goose egg, and “how to walk on the water, a proper secret,” by attaching empty drums to your feet and seeming to glide over the water.

Most colleges and high schools have a Shakespeare society and regularly perform his works. You might invite an actor or two from a local theater company or college to perform, or ask guests to act out favorite scenes.

During great feasts pages might read passages from ancient Greek and Roman writers. Guests too were expected to recite poetry or sing. Songbooks such as

A Banquet of Dantie Conceits

(1588), containing assorted ballads, were available. One song asked what has the strongest influence over men: wine, women, or the king.

O WHAT A THING OF STRENGTH IS WINE:

OF HOW GREAT POWER AND MIGHT:

FOR IT DECEIVETH EVERY ONE,

THAT TAKES THEREIN DELIGHT.

Paul Hentzner, a German travel writer visiting England in the late 1500s, wrote of the English, “They excel in Dancing and Music, for they are active and lively.”

There are many recordings of Elizabethan music that can serve as background music during your dinner. If you prefer livelier music, select the tunes from one of the Shakespeare-inspired musicals such as

Kiss Me Kate

or

West Side Story.

ATTIRE

You might suggest that guests wear actor’s basic black to your Elizabethan party and provide them with props for dress-up. Thrift shops, tag sales, and borrowing from local theater groups, schools, or dressmakers can yield some innovative finds.

STAGE DIRECTIONS

.....

TABLE TALK

… LET IT SERVE FOR TABLE-TALK;

THEN, HOWSOE’ER THOU SPEAK’ST, ’MONG OTHER THINGS

I SHALL DIGEST IT.

The Merchant of Venice, 3.5

Elizabethan etiquette and “table-talk” books gave advice on how to engage in light banter, make puns, tell proverbs, riddles, and even jokes during dinner.