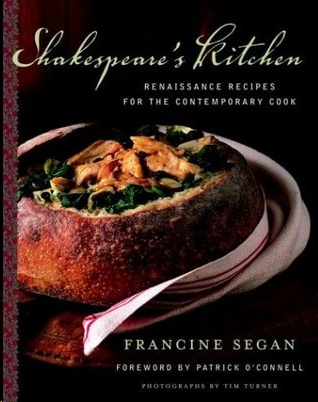

Shakespeare's Kitchen

Read Shakespeare's Kitchen Online

Authors: Francine Segan

COPYRIGHT © 2003 BY FRANCINE SEGAN

PHOTOGRAPHS COPYRIGHT © 2003 BY TIM TURNER

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNDER INTERNATIONAL AND PAN-AMERICAN COPYRIGHT CONVENTIONS. PUBLISHED IN THE UNITED STATES BY RANDOM HOUSE, AN IMPRINT OF THE RANDOM HOUSE PUBLISHING GROUP, A DIVISION OF RANDOM HOUSE, INC., NEW YORK, AND SIMULTANEOUSLY IN CANADA BY RANDOM HOUSE OF CANADA LIMITED, TORONTO.

RANDOM HOUSE AND COLOPHON ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF RANDOM HOUSE, INC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

SEGAN, FRANCINE.

SHAKESPEARE’S KITCHEN: RENAISSANCE RECIPES FOR THE CONTEMPORARY COOK/ FRANCINE SEGAN; PHOTOGRAPHS BY TIM TURNER.—1ST ED.

P. CM.

eISBN: 978-0-679-64498-9

1. COOKERY, ITALIAN. I. TITLE.

TX723 .S377 2003

641.5945—DC21 2002036839

RANDOM HOUSE WEBSITE ADDRESS:

WWW.RANDOMHOUSE.COM

v3.1

To my soul mate, Marc Segan,

our wonderful children, Samantha and Max,

and to my mother, Eleanor Oddo

Preface

S

HAKESPEARE IS A FUNDAMENTAL PART OF OUR AMERICAN CULTURE

, and we Americans have long had a fascination with his life and works. We quote him daily, often without knowing it. “By the book,” “the be all and end all,” “seen better days,” “for goodness’ sake,” “not budge an inch,” and “eaten me out of house and home” are all Shakespeare’s words. His plays are produced more than those of any other writer in history. Hollywood has created hundreds of movies inspired by him, and countless theaters across America bring Shakespeare’s plays to the stage each year.

America shares a culinary history with many nations, but foremost is England. The Pilgrims who arrived at Plymouth Rock were Shakespeare’s contemporaries and they brought with them their cookbooks from England. In those early years there was no time for culinary innovation, so settlers adapted the recipes as best they could to the indigenous foods found in their new world.

At the time of our independence in 1776, America had not yet developed a unique culinary signature. In fact, it wasn’t until 1796 that the first American cookbook,

American Cookery

by Amelia Simmons, was written and published on these shores. Until then all the cookbooks in America were European imports.

It is from the English that we inherit much of what we now think of as “American” food. Apple pie, stuffed turkey, and even gingerbread houses all originate in England. The roots of American cooking are to be found in Shakespeare’s England.

It is impossible to turn back the clock and prepare dishes precisely as they were made in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Spices, meat, fish, and vegetables have altered over the years with improved cultivation and scientific intervention. Cooking techniques have also changed considerably since Shakespeare’s time. We no longer boil in cauldrons suspended from cranes over a hearth or bake in iron boxes and brick ovens. However, it is possible to achieve a fairly close approximation of the foods eaten four hundred years ago by taking Shakespeare’s advice to “piece out our imperfections with [our] thoughts” (

King Henry V

).

The cookbooks published during the late 1500s and early 1600s provide a fascinating window into Shakespeare’s world. They show not only how people cooked and ate, but also how they wrote and organized their thoughts. For example, Elizabethan recipes were written as running text and did not include the details we are used to seeing in modern cookbooks, such as recipe titles and ingredient lists. Similarly, Shakespeare’s plays were also originally written and published without the numbered acts and scenes we are so accustomed to today.

In those days, cookbook authors assumed that the chef knew the proper proportions of ingredients, so quantities were rarely specified. “As your eye shall advise you” or “as your cook’s mouth shall serve him” was as specific as they got. When quantities were mentioned it was with colorful and sometimes vague references such as “four penny worth of Saffron,” “little cakes as broad as a shilling,” and “cut as thick as a half crown piece.”

There were no cooking thermometers for measurements more precise than “beware you burn it not” and “sufficiently bak’t.” Clocks and timepieces, expensive in Shakespeare’s day, were rarely found in kitchens, so that cooking times either were not expressed or were given in other terms such as “you will know it is cooked when it sticks to the spoon” or, as an Italian cookbook of the period notes, “cook for no more than two Our Fathers.”

In

Shakespeare’s Kitchen,

the original text is included for many recipes, with spelling, grammar, syntax, and punctuation left intact. Spelling was not yet standardized in Shakespeare’s day, so you may find the same word spelled differently even within the same recipe. Pie may be “pye,” flour “flower,” and raisins anything from “raysons” to “raisyns.”

Some instructions sound amusing to our modern ears, for example, “Thrust your Knife into the flesh of your Legge down as deep, as your finger is long.”

Charming phrases in these old recipes include:

“Brush off the golde with the foot of an hare or conie.” Gold was commonly used in cooking and a rabbit’s foot often served as a basting brush.

“Eggs in Moon Shine.” Moonshine was a fanciful term for the white sauce in this dish and had nothing to do with liquor, home-brewed or otherwise.

“Put in a little piece of butter as much as a walnut,” “as much white salt as will into an Egshell,” and “make the balls as big as nutmeg or musket bullet,” or as “big as a tennis ball” are all terms used by the Elizabethans to describe quantities by reference to familiar objects.

Although I have taken recipes from many different sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cookbooks, I do have a few favorite authors. I borrowed heavily from Robert May’s

Accomplisht Cook,

in part because his is by far the largest cookbook of the era with thirteen hundred recipes, but also because he is clearly a cook’s cook, a professional chef, unlike other authors, who were writers first and cookbook writers only second. Robert May was a professional full-time chef to the nobility who began his cooking apprenticeship at age twelve with his father, also a career chef.

Robert May wrote his first and only cookbook in 1660 at age seventy. His recipes span several decades of culinary history, back to Shakespeare’s day and even to Medieval styles of dining and food preparation. Robert May speaks lovingly of the bygone era of elaborate preparations for noblemen’s special feasts “before good House-keeping had left England.”

Most chapters in

Shakespeare’s Kitchen

showcase a particular Elizabethan cookbook writer. In the Basics chapter, you will meet cookbook author, poet, and inventor Sir Hugh Plat, who was knighted by King James I for his innovations in agriculture. In the Desserts chapter (“The Banquet”) you’ll get to know Sarah Longe, who shares recipes enjoyed by Queen Elizabeth I and King James I; and in the Appetizers chapter you will meet Gervase Markham, whose 1615 cookbook begins: “Eating and drinking are a very pretty invention.”

Allow me to introduce you to these wonderful Elizabethan cooks, their recipes, and the foods and dining customs of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe as we journey back to Shakespeare’s England and back to our culinary roots.

Acknowledgments

MY DEEPEST GRATITUDE TO

Mary Bahr, Judi Carle, and Tim Turner for their expert guidance and wonderful insights throughout every step of the process.

Appreciation to Agatha and Valentina Gourmet Food in New York City; Louis Balducci; Elise Abrams Antiques, Great Barrington, Massachusetts; Lock Stock and Barrel Gourmet Foods and Wine Merchants, Great Barrington, Massachusetts; Kuttner Prop Rental and The Prop Company in New York City. Thanks to Allison Fishman, Marcia Kiesel, Wes Martin, Judy Singer, Lee Elman, Bob and Toni Strassler, Laura Chester, Honey Sharp Garden Design, Berkshire Botanical Garden, Windy Hill Nursery, Adrian Van Zon, Dorothy Denburg, Moira Hodgson, Bill Rice, Elliot Brown, Nach Waxman, and Professor Roger Deakins.

Special thanks to the New York Public Library, Rare Books Division; Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations; the Huntington Library; the Folger Shakespeare Library; and to Arlene Shaner, New York Academy of Medicine Library, Malloch Rare Books Room.

And most important, thank you to Shakespeare festivals everywhere for keeping us connected to Shakespeare’s works, as the Bard would have most wanted, with live actors on a real stage.

Contents