Running on Empty (5 page)

Authors: Marshall Ulrich

In time, when we started posting some respectable finishes in or near the top ten, Team Stray Dogs attracted a sports agent to represent us, which meant sponsorships. Early on, single-event entry fees started at about $15,000 per team, and during the late 1990s they steadily rose to about $25,000 per team. We were grateful to have corporate support from Pharmanex (a division of Nu Skin) for our Morocco and Patagonia adventures and later from DuPont, which underwrote numerous races and for which we tested clothing and fibers. Incidentally, there was no financial profit in it for us athletesânot that we cared, as we were doing what we loved on someone else's dime. But the agent made some good money, and the corporate sponsors got exposure when MTV, the Discovery Channel, USA Network, ESPN, or Nat Geo broadcast the Eco-Challenges or Raids Gauloises.

Altogether, the running and the adventure racing took me away from home and work three to six weeks out of the year, not an unreasonable amount of time, I thought. Still, training runs and local races that ranged from fifty kilometers to one hundred miles consumed most of my “downtime,” leaving little for family or a social life. It was extremely rare for me to read a book, go to the movies, or watch TV. Today, it surprises me when I discover some sitcom of which I was completely unaware during the eighties. I still find “new” episodes of

Seinfeld

hilarious.

Seinfeld

hilarious.

So I worked. I spent time with my kids. I ran. I raced. And I thought up new ways of torturing myself, wanting to do something each year that no one else had ever done before.

Â

It felt as if 120-volt shocks probed my legs with every step. Arriving at the top of Towne's Pass in Death Valley National Park, I'd already been running for five days straight, more than three hundred miles across the desert floor and up Mount Whitneyâand I still had over two hundred miles and another summit of Mount Whitney to go. People surrounded me, giving me advice. But I was in a fog, stumbling around in my own world with memories and voices from the past floating through the haze. Self-doubt clouded my mind:

I can't do it anymore. The pain is too much. I have to stop.

I can't do it anymore. The pain is too much. I have to stop.

In July 2001, in honor of my fiftieth birthday, I was attempting to complete the first-ever Badwater Quad: running the Death Valley course four times in a row, plus tacking on a few extra miles so I could climb the mountain twice. When I was done, it would be four crossings, 584 miles, and a total elevation change of 96,000 feet, essentially nonstop.

A little more than halfway through and after 130 hours, I was feeling completely used up, suffering from severe tendonitis. No wonder. During one course completion at Badwater, your feet strike the ground more than three hundred thousand times, absorbing the impact of four million poundsâthe equivalent of hitting the pavement after falling three thousand feet, or being struck in a head-on collision with a jumbo jet. Ask around at your local running shop, and they'll tell you runner's tendonitis is a “typical overuse injury.” Well, sure, I was in a state of overuse, but that's where ultrarunners live, in that place where you feel as if there's nothing left, no more energy, no more reason, no more sanity, no more will to go farther. Then you push forward anyway, step after step, even though every cell in your body tells you to stop. And you discover that you

can

go on.

can

go on.

At this time in my life, I was running on empty in a larger sense, too, still punishing myself, still trying to prove that I could survive just about anything, still trying to outrun my mortality. In the twenty years since Jean's death, I'd racked up a list of accomplishments as I'd strived to fulfill my definition of success and compensate for what I perceived as my personal shortcomings. Nearly all of my family relationships were strained. My dad, brother, and sister thought I was crazy for all the time I devoted to running, and they didn't like that it took me away from our business. Dad had loaned me start-up money, and since then Steve and Lonna had bought into the business and were working in Greeley while I took care of things in Fort Morgan, so they each had a vested interest and strong opinions. I'd married and divorced Danette, then done it all over again with another woman, and I considered all three of my marriages failuresâI was alone, wasn't I? My relationship with Danette was tense, and my children (now eleven, eighteen, and twenty-three), resented all the time I'd spent away from them.

So, sure, I'd raced at all the major events, won some, and broken records. In my thirties, I'd discovered my talent for ultrarunning; in my forties, I'd taken it to another level with my creative extremes, and diversified with adventure racing; now, as I entered my fifties, I was something of a celebrity among endurance athletes.

Trail Runner

magazine would call me one of the legends of the trail,

Outside

would crown me “Endurance King,” and

Adventure Sports

would highlight me as an athlete “Over Fifty and Kicking Your Butt.”

Trail Runner

magazine would call me one of the legends of the trail,

Outside

would crown me “Endurance King,” and

Adventure Sports

would highlight me as an athlete “Over Fifty and Kicking Your Butt.”

Good for me. I was a badass.

At least my exploits had taught me ways to get myself through tough spots like the one I was experiencing on Towne's Pass, such as using my athletic pursuits to raise money for a charity I cared about, a religious order of sisters serving women and children. On that day, I pushed through the pain by reminding myself that I wasn't doing it only for me. My suffering had a purpose. Anyone who's walked or run a few miles to benefit a cause knows how motivating this can be. Just when you start to feel as if you have nothing left to give, you remember how difficult someone else's life is, and you can keep going. Perspective does wonders. (I love this sign, spotted at a marathon to benefit cancer research: “Blisters don't require chemo.”) So I strapped a bag of ice onto each shin and slogged it out for the final 232 miles, my legs the center of my universe, tormenting me for the next five days, all the way to the finish.

Â

Badwater Quad, check.

Now just a couple of goals nagged at me still, like some kind of extreme bucket list. Before I departed this earth, I wanted to climb Mount Everest and realize my boyhood dream. And I had this other ambition to run across the United States, something I considered the ultimate ultra: more than three thousand miles from shore to shore, across all kinds of terrain. It would be the run of a lifetime, the most extreme challenge I'd ever attempted. In the same way I'd thrilled to the early stories of the Everest mountaineers, I found the travails of those who'd managed to cross our country on foot completely riveting. I wanted to experience all of that for myself, firsthand.

Now just a couple of goals nagged at me still, like some kind of extreme bucket list. Before I departed this earth, I wanted to climb Mount Everest and realize my boyhood dream. And I had this other ambition to run across the United States, something I considered the ultimate ultra: more than three thousand miles from shore to shore, across all kinds of terrain. It would be the run of a lifetime, the most extreme challenge I'd ever attempted. In the same way I'd thrilled to the early stories of the Everest mountaineers, I found the travails of those who'd managed to cross our country on foot completely riveting. I wanted to experience all of that for myself, firsthand.

Â

The month after my Badwater Quad, I was still so burnt from it that I couldn't compete in that year's Leadville Trail 100, so I was happy to help a friend get the job done. When I first started ultrarunning, there were no coaches, no experts, no manuals, no playbooks. Sometimes, there wasn't even a marked courseâyou just had to get yourself from point A to point B, from starting line to finish line, however you saw fit to go. Forget frequent water stations and cheering onlookers. Ultrarunning is all about going it aloneâor, if you're smart, you might draft a friend or two to pace you by running alongside you, or to “crew” you by providing first aid or any other assistance you might need, from blister care to icing you down. When you're out in the middle of nowhere, with runners miles apart and covering extreme distances on trails few other folks ever get the chance to see, it's an advantage to have someone else with you, ideally someone with endurance and experience.

Although by 2001 the Leadville race had become more organized, Theresa Daus-Weber had asked me to crew and then pace her back over Sugar Loaf Pass because of my wealth of experience on the Leadville course. Waiting for her to arrive at an aid station, I met Theresa's friend, Heather Vose, who introduced herself and her dog. While Ripley sniffed me out, Heather told me she'd gotten to know Theresa at their place of work, an environmental consulting firm in Denver. She'd come out to watch Theresa and was curious about “this ultrarunning thing,” which she'd heard of only recently.

Smart and sexy, Heather intrigued me. She was also younger than I, at least ten years my junior if I guessed right. Maybe more.

Does it matter?

Over the next fifteen hours of the race, I thought about that. And her. A lot. So I was pleased when I saw Heather again as Theresa crossed the finish line, making her one of only two women who've completed the course eleven times. Heather and I quietly celebrated our friend's victory, and I found myself growing more and more attracted to her. What an extraordinary woman!

Does it matter?

Over the next fifteen hours of the race, I thought about that. And her. A lot. So I was pleased when I saw Heather again as Theresa crossed the finish line, making her one of only two women who've completed the course eleven times. Heather and I quietly celebrated our friend's victory, and I found myself growing more and more attracted to her. What an extraordinary woman!

Years ago, I'd decided I wasn't marriage material: With my track record, I didn't want to subject any more women to being tied to me that way. But who'd said anything about marriage? I just wanted to talk to Heather again. Sadly, I anticipated I'd never get the chance. As we said our good-byes, I hugged her and kissed her lightly on the cheek.

After the race, though, Heather and I exchanged some e-mail messages, and a few months later, I joined her, Theresa, and another friend for Christmas dinner in the mountains near Leadville. We went snowshoeing, shared some laughs, and told stories while Heather and I checked each other out surreptitiously. At the end of the day, I drove Heather home, we stood on her doorstep, and feeling uncharacteristically bold, I took her in my arms for our first kiss. As she returned my embrace, Heather's snowshoes clattered to the ground, and that was the beginning of our romance.

In April, Heather asked if she could move in with me; we were spending so much time together that it just made sense. I hadn't expected to be ready for something like that so soon in our relationship, or everâhell, I was fifty and set in my waysâbut this straightforward, passionate woman brought out feelings long dormant in me, and I agreed, happy to have her near.

Â

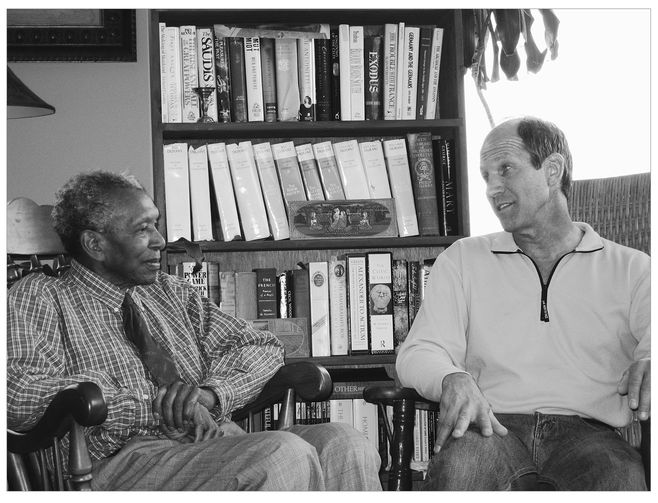

A month later, she kissed me good-bye when I left to embark on my first mountaineering experience. Sometime before, professional mountaineer Gary Scott had called me after reading an article in

Outside

magazine that mentioned my desire to scale Mount Everest. We'd never met, but he was interested in helping me gain some experience, and he advised me that although I was already skilled with some climbing from my adventure racing, I'd better go up a few seriously big mountains before attempting Everest. He'd be happy to guide me, he said, and then suggested we put together a team to climb Denali; at just over 20,000 feet in elevation, it's the highest peak in North America, the perfect place to start my training, and we could do this expedition inexpensively. Great! As usual, I'd lucked into the cheapest way possible to try something new. I contacted some friends I knew from adventure racing, Charlie Engle and Tony DiZinno, and Gary contacted a young man with some mountaineering experience, Aron Ralston. We got sponsors, too, who gave us backpacks and climbing gear, and Gary led us to the top. When I handled the altitude well, it gave me the confidence I needed to climb Aconcagua, the highest peak in South America, less than a year after that. I was on my way to Everest, mountain by mountain, now determined to climb all Seven Summits.

Outside

magazine that mentioned my desire to scale Mount Everest. We'd never met, but he was interested in helping me gain some experience, and he advised me that although I was already skilled with some climbing from my adventure racing, I'd better go up a few seriously big mountains before attempting Everest. He'd be happy to guide me, he said, and then suggested we put together a team to climb Denali; at just over 20,000 feet in elevation, it's the highest peak in North America, the perfect place to start my training, and we could do this expedition inexpensively. Great! As usual, I'd lucked into the cheapest way possible to try something new. I contacted some friends I knew from adventure racing, Charlie Engle and Tony DiZinno, and Gary contacted a young man with some mountaineering experience, Aron Ralston. We got sponsors, too, who gave us backpacks and climbing gear, and Gary led us to the top. When I handled the altitude well, it gave me the confidence I needed to climb Aconcagua, the highest peak in South America, less than a year after that. I was on my way to Everest, mountain by mountain, now determined to climb all Seven Summits.

Â

In another year, I'd changed my mind completely about getting married again, and on Christmas Day in 2002, I gave Heather a stuffed moose with an engagement ring hung on a gold chain around its neck. At first, she thought the moose was all there was to it, but then she noticed the ring and I made my proposal. To my relief and excitement, she said yes. With a wink at my checkered romantic past, we exchanged our vows on April Fools' Day, 2003, and enjoyed a delayed honeymoon trip to Africa in July, where we summited Kilimanjaro together. I'd found a partner in her, a woman who loved me in spite of my flaws and who was even willing to join me in a few of my obsessions. We'd both entered this relationship with serious misgivings, but by the time we were standing on that mountaintop together, we'd let the walls down. I'd come to understand what made her who she was, and what she'd been through in her own life, and I'd shared my own story. She'd already convinced me that I wasn't unfit to be her husband, and was helping me to finally deal with my grief over Jean's death and my shortcomings as a father. Through my guilt and regret and other messy feelings, she was undeterred. She'd become emotional ballast for me, my refuge and my rock.

A year after our summit of Kilimanjaro, I was making plans for us to climb Mount Elbrus, the highest peak in Europe, when I came across something startling, a website for “Everest 10000.”

What's this?

Sitting at my computer, I read about a Russian adventure team, led by Alex Abramov, and its Everest expedition, which would cost me $10,000 (a bargain!) to join if they accepted me. I called Alex right away to express my enthusiasm, share my athletic résumé with him, and ask for a place on his team.

What's this?

Sitting at my computer, I read about a Russian adventure team, led by Alex Abramov, and its Everest expedition, which would cost me $10,000 (a bargain!) to join if they accepted me. I called Alex right away to express my enthusiasm, share my athletic résumé with him, and ask for a place on his team.

“One spot open, sure. You send money right away.”

Four weeks later, I was sitting in base camp in Tibet at 17,160 feet with the Russians, ready to attempt the climb to summit the highest mountain in the world.

Â

Mount Everest, check.

I came home with all ten toes and fingers but lost a few brain cells to sleep deprivation and oxygen deprivation. Despite temperatures that plummeted well below zero, winds that whipped us at thirty or more miles per hour, claustrophobia, weight loss, and nearly being swept away in a torrential glacial stream, I made it back down alive, my lifelong dream fulfilled. Heather met me on the trail just outside base camp, where she'd waited for my return with her father. We held each other quietly. Nothing else mattered to me in that moment but that we were together, and even Everest seemed suddenly insignificant.

I came home with all ten toes and fingers but lost a few brain cells to sleep deprivation and oxygen deprivation. Despite temperatures that plummeted well below zero, winds that whipped us at thirty or more miles per hour, claustrophobia, weight loss, and nearly being swept away in a torrential glacial stream, I made it back down alive, my lifelong dream fulfilled. Heather met me on the trail just outside base camp, where she'd waited for my return with her father. We held each other quietly. Nothing else mattered to me in that moment but that we were together, and even Everest seemed suddenly insignificant.

Other books

Catching Liam (Good Girls Don't) by Bleu, Sophia

Gargoyles by Thomas Bernhard

Imaginative Experience by Mary Wesley

Warrior's Craft Four Bikers and a Witch by Cheryl Dragon

Checking It Twice by Jodi Redford

Dragon Airways by Brian Rathbone

Augustus by Allan Massie

Journey of the Magi by Barbara Edwards

Harmattan by Weston, Gavin

The Enchanter of Rangel: Child of War Book 1 by Lissett, Alonna