Running on Empty (2 page)

Authors: Marshall Ulrich

And that's when a shadow blocked out the sun. A man stood over him, then squatted down. His voice was calm, quiet, lighthearted. He wasn't trying to buck McKinney up so much as talk the race down. Not a big deal, he told McKinney; get some water down your throat, maybe some tapioca pudding, and then look around. Isn't this place awesome? How many other people get a chance to see this? We're a couple of lucky guys, you and I. . . . Did you finish that pudding? Good, try a banana....

The year before, Marshall had come straight to Badwater after reaching the top of Mount Everest. Marshall had always wanted to make the climb, and the only window had opened before Badwater. Rather than choose between the challenges of a lifetime for anyone else, he'd once again decided to just live a little harder than anyone else. He knew the consequences: No matter who you are, you're half the man you were by the time you get down from Everest. You've lost at least one-third of your muscle mass, and count yourself lucky if you're not dehydrated, frostbitten, malnourished, and snow-blind. Somehow, Marshall had managed to hustle his muscle-depleted self off the Himalayas, and then, for good measure, he headed to Russia to reach the summit of Mount Elbrus before returning halfway around the globe to complete Badwater.

The year he met Frank McKinney was mild by Marshall's standards; all he'd done was complete the Seven Summits, including climbing Mount Vinson in Antarctica, before coming here to squat on 200-degree asphalt with some guy who really wished he'd go away.

Marshall chatted with McKinney for an hour

.

A full hour, in the middle of a race that he'd won four times and exactly at a time when he should have been worrying about title number five instead of teaching Badwater 101 to an inexperienced freshman. But it worked; bit by bit, McKinney began to feel better. He got to his feet and tested his legs. Not

totally

like wet newspaper. He began to shuffle, then jog, then runâand he kept going until he crossed the finish line more than a day later.

.

A full hour, in the middle of a race that he'd won four times and exactly at a time when he should have been worrying about title number five instead of teaching Badwater 101 to an inexperienced freshman. But it worked; bit by bit, McKinney began to feel better. He got to his feet and tested his legs. Not

totally

like wet newspaper. He began to shuffle, then jog, then runâand he kept going until he crossed the finish line more than a day later.

When I finally got the chance to ask Marshall about it, I had one question: “Why?” Every second you spend under the Death Valley sun increases your risk of ending up in the hospital with an emergency IV in your arm, and no one knew that better than Marshall. Once, he'd watched Lisa Smith-Batchen, the supertalented desert specialist and a former winner of a six-day race across the Sahara, get pulled from Badwater and rushed to the ER. So why was he risking his raceâpotentially, his

lifeâ

for this guy?

lifeâ

for this guy?

Marshall didn't know. And that's when I discovered, absolutely by accident, the key to his superhuman strength: Marshall keeps going forward because there's no looking back. He kept running, adventure racing, and climbing because those activities demand movement in a single direction. Even in his sleep, as his wife would discover, Marshall can rest only if he's in motion. You can answer

why

only with a look in the rearview mirror, and those were two things

â

rear views and mirrors

â

that Marshall absolutely did not deal with.

why

only with a look in the rearview mirror, and those were two things

â

rear views and mirrors

â

that Marshall absolutely did not deal with.

That's how it was when I met him in 2005. I'd had the spectacular luck to attend a running camp in Idaho's Grand Tetons organized by Marshall and Lisa. He was awe-inspiring: kind, funny, happy-go-lucky, insightful, a sharp mind with a keen biomechanical eye. Two of the greatest gifts you can give an endurance athlete are the chance to run with Marshall Ulrich and the chance to pick his brain, and I was delighted to get one because I knew the other was off the market.

And then, something happened. After almost thirty years of keeping his eyes drilled forward and his thoughts to himself, Marshall woke up. He realized, with one of those bursts of clarity that are so frightening that you hope you never have one again, what had happened to him. All those stories he'd spent a lifetime avoiding were locking together into a tragically disturbing pattern.

If only he'd realized it before . . .

If only he'd realized it before . . .

So what was it? What was it that brought Marshall Ulrich back to the world, and what has happened since then? Ordinarily, you'd have to wait for the story to pass from mouth to mouth, making the rounds of the rumor circuit. But now, for the first time, Marshall can tell you for himself.

Â

CHRISTOPHER McDOUGALL

author of

Born to Run

author of

Born to Run

Prologue

Born on the fourth of July, I was always suitably independent. Stubborn, too, and competitive. By the age of ten, I'd already figured out that when my older brother and I got into trouble, whomever Dad caught first was going to get it the worst. If I could outrun Steve, sometimes I could avoid a lickin' altogether. Dad's legs weren't in the best shapeâhe'd fought in World War II and still suffered the effects of injuries he'd sustained at the Battle of the Bulgeâand I was usually way out in front of both of them, racing across the fields at top speed. Sorry, Steve.

My family lived in a simple ranch-style house in the middle of an eighty-acre dairy farm near Kersey, Colorado. We kept a herd of about sixty cows and grew corn and alfalfa to feed them. Mom, Dad, my sister, Lonna, Steve, and I all worked to keep things going, but my brother and I were constant companions, laboring together in the fields and at the barn from the time we were big enough to wield pitchforks. At the ripe old age of eight, I taught myself to drive a tractor when Dad wasn't looking, and after that, Steve and I were in business. Three or four times a year, the alfalfa had to be cut, dried, baled, loaded onto a “sled” we pulled behind the tractor, then stacked in the back of a truck. In our teen years, as we grew stronger, it was a badge of honor to be able to tell our parents what we'd accomplished in a day. All on our own we could, for example, put up more than two thousand square balesâthat's a couple hundred bales, at seventy pounds each, per hour. It was hard but gratifying labor, and although our parents didn't materially reward us for it, we certainly felt their approval.

Sometimes it was fun, too. Steve and I made most chores into a contest: “Who can bale and stack the most hay today? Ready, set, go!” He almost always beat me at this, which I hope in some way compensates for all the punishment he took on my behalf.

We worked seven days a week, before and after school, and all day Saturday, but Sunday afternoons were my own. My comic books, sketch-pad, and adventure novels kept me company on the back porch, my refuge year-round, even in winter when it wasn't heated. Engrossed in a tale like

The Call of the Wild,

I could feel the chill and indulge myself in the fantasy of being Buck, the noble sled dog, braving the frigid Yukon. I also loved to draw, especially my comic book heroes as they performed superhuman feats, and Mom always encouraged these interestsâreading and artâby keeping me in good supply of books and pencils and paper.

The Call of the Wild,

I could feel the chill and indulge myself in the fantasy of being Buck, the noble sled dog, braving the frigid Yukon. I also loved to draw, especially my comic book heroes as they performed superhuman feats, and Mom always encouraged these interestsâreading and artâby keeping me in good supply of books and pencils and paper.

The fictional stories fired my imagination, while TV coverage of the true-life exploits of the early Everest mountaineers made me want to test my farm-hardened strength against the natural world. I was two years old in 1953 when Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay ascended the 29,035 feet, the first men to reach the top and come back alive. Before my adolescence, more than a dozen summiteers had conquered Mount Everest, and many, many more have done it since. Not without paying a price, however. Images of their hands, so dramatic on our black-and-white television's screen, fascinated me: Nails and knuckles swollen and darkened by severe frostbite, they had clawed their way down the mountainside as the wind blew, sounding an unyielding, eerie, and violent noise. Indeed, many climbers returned with fingers and toes frozen off, sacrificed to the gods of great adventure on the highest mountain on earth. Clearly, not just anyone would do this, but it was equally evident to my young eyes that it could be done. Besides, Mom was always telling us kids that we could accomplish

anything

. At five years old, I'd already decided that I wanted to climb mountains. Someday, I'd be one of the elevated few, keeping company with those exceptional people who brave the elements, tough it out, go the distance. Someday, I'd be a man who, as Jack London put it, “sounds the deeps of his nature.”

anything

. At five years old, I'd already decided that I wanted to climb mountains. Someday, I'd be one of the elevated few, keeping company with those exceptional people who brave the elements, tough it out, go the distance. Someday, I'd be a man who, as Jack London put it, “sounds the deeps of his nature.”

Yet the demands of the farm kept me in the here and now. There was

always

work to be done. Crops to be tended, harvested, stored. Cows to be milked, fed, moved. Sheds to be cleaned and filled with straw. Machinery to be maintained, fixed, and, on incredibly rare occasions, junked. Dad, a real no-nonsense businessman in addition to being a farmer, was loath to throw anything away or buy anything new. The one time we told him about our neighbors' suggestion that we get a new conveyor chain for the manure spreader, because they replaced theirs every couple of years and never had trouble with breakdowns, he looked at us like we'd lost our minds. His stern expression said it all: “You boys get on out there and use the links I bought you to fix that chain we've got.”

always

work to be done. Crops to be tended, harvested, stored. Cows to be milked, fed, moved. Sheds to be cleaned and filled with straw. Machinery to be maintained, fixed, and, on incredibly rare occasions, junked. Dad, a real no-nonsense businessman in addition to being a farmer, was loath to throw anything away or buy anything new. The one time we told him about our neighbors' suggestion that we get a new conveyor chain for the manure spreader, because they replaced theirs every couple of years and never had trouble with breakdowns, he looked at us like we'd lost our minds. His stern expression said it all: “You boys get on out there and use the links I bought you to fix that chain we've got.”

Â

When I graduated from high school, in 1969, no one was surprised that I'd achieved less than a 2.0 grade-point average. Homework had always been a low priority, somewhere between visits to the barbershop and cleaning my room. In other words, I rarely studied, and my results reflected my schoolwork ethic.

That August, a month after my eighteenth birthday, a dairy farm much larger than ours was home to the Woodstock Festival in New York. No, I didn't attend, but I was well aware that we were in an era of free love and draft cards. By then I was seeing Jean Schmid, a girl I'd met a couple of years earlier on a blind date at a church hayride, and we'd go into Boulder to listen to the Freddie Henchie Band and gawk at all the hippies on “The Hill,” which was Colorado's answer to Haight-Ashbury.

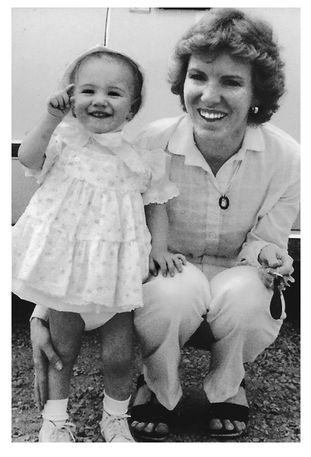

Jean and I had fallen in love quickly, proving that opposites attract: She was as socially outgoing as I was shy. She had a crackerjack mind, hazel eyes, and an infectious laugh. She also knew what she wanted, enjoyed a joke, and was nurturing in a way I'd never experiencedâall traits I found irresistible. A slight young woman at four feet, eleven inches and eighty-seven pounds, she'd climbed onto my lap on our second date and started making out with me, letting me know exactly how she felt. I was completely taken with her, and by the time we were seventeen, I knew I wanted to spend the rest of my life with Jean.

A few years later, after I'd done my time in a junior college, and put in a year of basic training with the Air National Guard, she agreed to marry me. She transferred to the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, where she continued to study journalism and I went into the fine arts program. In June 1974, we received our diplomas, tied the knot, and started my first business, all in the same week.

Although I'd spent the last few years working on weaving, sculpture, and painting, I'd decided to go into the family business, and opened a rendering plant. Buying cattle carcasses and processing the dead animals to make dog food, I jokingly referred to myself as a “used cow dealer.”

Because I was so busy with the new operation and Jean was pursuing a law degree, we put off having children for a while, but as soon as she had that locked up, we were ready. In fact, Jean sat for the bar when she was eight months pregnant, and as expected, she handily passed the exam.

Life seemed full of promise. Both of us had worked hard for what we'd achieved, and with a baby on the way we felt as if we had everything we'd ever hoped for. In 1979, after twelve hours of labor, Jean gave birth to our daughter by cesarean section. It was considered unorthodox at the time, but I was allowed in the operating room when the doctors pulled our girl, healthy and squalling, from her mother's womb, and I took many, many photographs of the birth. Calling such a moment miraculous hardly describes the joy and intimacy of it, but that's what it seemed to us. Our parents, siblings, and friends came by to celebrate our baby daughter, Elaine, the first grandchild for both sides of the family. I was sure life couldn't get any better, and I was right. Everything was perfect.

A year later, just after we'd bought our first house and little Elaine was starting to toddle around the yard, we got the devastating news: Jean had invasive breast cancer, which had already spread to her lymph nodes. Telling us about it, the doctor tried to remain professionally detached but was visibly rattled by what he'd seen on the mammography films. He scheduled Jean for surgery immediately, and within just a couple of days, she underwent a double mastectomy. By the week's end she began chemotherapy.

During Jean's first treatment, she made small talk with the chemotherapist and mentioned that we were looking forward to having more children; little ones make life so rich, take you outside yourself, and help you to keep things in perspectiveâthey even make trials like this one bearable. Tending to her IV, the doctor offhandedly told her we should wait. Well, of course, we'd hold off until Jean was feeling better . . . No, that's not what he meant. He explained that he didn't know if she'd be around to raise them. That stunned and silenced her, and I could imagine what she was thinking: Would she live to see Elaine get out of diapers, much less become an adult?

Other books

Yellowthread Street by William Marshall

Monday to Friday Man by Alice Peterson

The Enemy Within by Sally Spencer

Glimmers of Change by Ginny Dye

Descent by Charlotte McConaghy

The Immaculate by Mark Morris

Kent Conwell - Tony Boudreaux 06 - Extracurricular Murder by Kent Conwell

The Sleeping Fury by Martin Armstrong

Her Cowboy Bears (BBW MMF Menage Shapeshifter Romance) by Tabitha O'Dell

A Lycan's Mate by Chandler Dee