Running on Empty (9 page)

Authors: Marshall Ulrich

“It's just who I am.”

It's also just what I needed: to get outdoors, to clear my head, to allow myself the time to think about what I'd experienced and then think about something else for a long, long time. I needed to run, to empty out the accumulated emotion, to strip myself of comfort and grieve the loss of these four men at my own pace, in my old, familiar fashion. As with Jean's death, running would provide a way for me to both deal with and avoid the emotional pain.

“Well, finally.” Heather took a deep breath. “The truth.”

My simple declaration had hit a nerve, and she knew that we'd reached the bottom of my particular mystery. All the other reasons I'd given her were versions of the truth, but this was new, truth with a capital T. It was then I began to see some kind of acceptance. She was going to give me her blessing; she knew that taking on these extreme tests of endurance, ones that demand not just athletic rigor but a unique brand of mental toughness, had become woven into the fabric of my being.

The transcontinental run would be about so much more than breaking a record, reliving history, or attempting some kind of extreme sightseeing trip. It would transcend the homage to my predecessors, although they were certainly on my mind. It would be a personal reckoning, an accounting of my character, that was sure to leave me scoured of everything but the essentials. It would mean running through the emptiness, beyond any pain, facing unimagined hardships, and on to . . . what? I didn't know. But I wanted to find out.

“You have to come with me.” I'd said this many times before.

Heather could see how much I wanted her to be a part of this endeavor, to support me in it not just with her words but with her presence. Truly, I didn't believe I could do it without her, and she knew that. She also knew, without me saying so, how cathartic this could be for me, what an incredible accomplishment it would be if I made it, and what it might cost us as a couple if she denied me.

She said yes, although she had no idea what she was signing up for.

Despite my background, neither did I, really. What we did know for certain was that it would be grueling, fraught with harsh realities, and incredibly hard on my fifty-seven-year-old body. And we knew I had to do it.

4.

Fool's Errand

Days 1â2

Â

Â

Â

Before the start of the race on September 13, 2008, when Heather and I arrived before dawn at San Francisco City Hall, I felt sick to my stomach whenever I thought about the impending grind. Everyone was making their last-minute preparations, especially confirming the day's route. (Our plan for leaving City Hall had been worked out the night before, a last-minute scramble caused by miscommunication or a lack of communication or someone dropping the ball, depending on whom you ask about it.) I tried to distract myself by cracking dumb jokes, giving my crew a hard time, and watching Charlie sign shoes and shirts for about a dozen guest runners who'd registered on the Running America website to come out and be a part of the start of this . . . thing.

Oh, shit. What have I gotten myself into?

I always say the only limitations are in your mind, and if you don't buy into those limits, you can do a helluva lot more than you imagine. So I let my mind wander away from my doubts and rest in my immediate surroundings. It wasn't yet fully light out, there wasn't much traffic, and the only people nearby were part of our deal. Guest runners stretching and warming up. The film crew getting ready to catch the beginning of what they expected to be an epic story

.

Charlie's and my race crews climbing in and out of the RVs and vans, double-checking supplies and reviewing the route.

.

Charlie's and my race crews climbing in and out of the RVs and vans, double-checking supplies and reviewing the route.

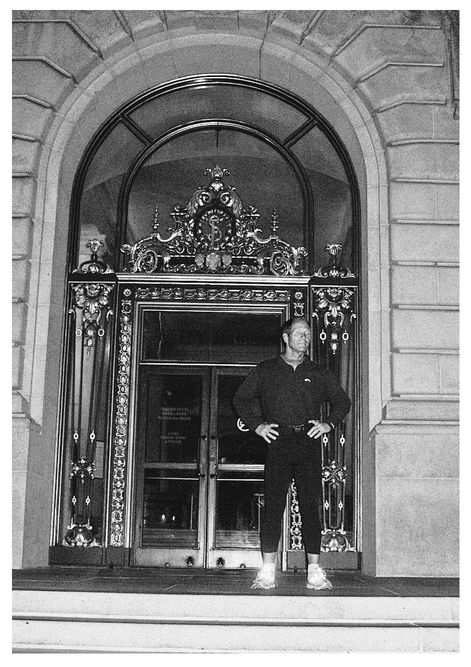

With the buzz of all this activity below me, I walked up the broad stairs to the city hall's main entrance and considered how much this imposing white building, with its enormous dome and soaring pillars, looked like so many other U.S. government centers, not so different from the one in lower Manhattan that would serve as our finish line. This architectural connection struck me as symbolicâanother continuity across the vast distance we'd coverâbut, to be honest, it didn't calm my jangling nerves. Trying to stay positive, I reflected on my original concept for the run and how it had all finally materialized with Charlie's efforts; the support of our sponsors who'd given equipment, gear, and money; and the keen interest of this talented documentary team hired by NEHST. Together, we'd see America one mile at a time, honor the history and diversity of our country, raise money and awareness for the United Way's campaign against childhood obesity, and literally follow in the footsteps of those who'd done this before. I'd had the lofty idea, too, that we'd somehow reintroduce America to Americans, showing how similar we all are while also celebrating the differences among the people we'd meet and the dramatically changing landscapes we'd traverse.

Now standing in front of the immense doors of City Hall, I waited for everyone to finish their preparations so we could get moving. This is where it would all begin. You could feel the excitement in the airâand the pity, too.

Welcome to California!

“The Golden State”

Â

Arrival date: 9/13/08 (Day 1)

Arrival time: 5:03 a.m.

Miles covered: 0

Miles to go: 3,063.2

Arrival time: 5:03 a.m.

Miles covered: 0

Miles to go: 3,063.2

Finally, just after five o'clock in the morning, Charlie and I stepped off the starting point together, chatting about the road ahead. He's taller than I am, slightly stooped, with broad shoulders and long legs, but I have a huge stride, so I had no trouble going alongside him. We traveled briskly up and down the hills on city streets, remaining intentionally oblivious to what lay beyond the next streetlight illuminating the long road ahead. We both knew this would be an ordeal, yet we felt some security in our partnership. With two runners, we'd increase our chances of at least one man making it into New York City, and if we could go all the way together (even if we finished separately), the ongoing competition would push us to set a new record. If one of us had to drop out, then he'd be there for the other guy, support him the rest of the way by sharing crew, gear, or whatever the remaining runner needed.

By about mile five, I settled into my own pace and moved away from Charlie and his group. A good friend, Chris Frost, stayed with me, and within hours of leaving City Hall, we'd run along the waterfront and crossed the Golden Gate Bridge, where another friend surprised us and ran with Chris and me through Sausalito.

I had company on and off for the rest of the day, even horsed around with Charlie on the RichmondâSan Rafael Bridge, cutting up for the cameras with him while we waited for a prearranged police escort.

We'd gotten off to a decent start together, despite tension that had developed between us during the months prior to the race. The guy could work a room, for sure, but his braggadocio and craving for the limelight had begun to rub me the wrong way. He'd neglected to include me or even mention my name in most of the pre-race publicity and sponsorships, and he'd made promises he'd failed to keep. Heather and I had begun to joke that I was the “invisible man.” On one hand, his disregard for my part in this event rankled. Yet he'd been instrumental in making it all come together, and once we were under way, I was grateful to him for keeping most of the attention on himself. I had enough to do, just staying focused on the run and not letting my concerns about the mileage get in my way, without having to worry about looking good for cameras or anyone else.

It took fifteen hours of active running to log the requisite seventy miles on that first day. My nerves had finally settled down by the time we'd goofed around on that bridge, and not long after that we'd finished our first marathon, stretched, and then cruised by the beautiful countryside of Napa Valley, stopping for the night in Fairfield a few hours after marathon number two. Heather and I bedded down in the RV with our friend and RV driver, Roger Kaufhold, and everyone elseâthe rest of my crew, Charlie, his crew, and the documentary teamâdrove many miles away to stay in the nearest Super 8 hotel, so I didn't get to hear about how he was doing, but my group felt good about the day's effort, with growing confidence that I could do this. I was tired, but not

that

tired. I was sore, but not

that

sore.

that

tired. I was sore, but not

that

sore.

The next morning, Charlie started a few miles behind me, having staked out his finish short of the full seventy miles on day one, but I didn't know if he was already having trouble or just being smart. My own legs felt heavy as I started off again on day two, a familiar feeling for any ultrarunner. My world was narrowing, too, another usual effect of long distances. The day before, I'd been keenly aware of the details of the landscape through the Bay Area, in particular certain smells that had marked our progress: first the urban aromas at City Hall, then the salty-fishy air of the wharf and the eucalyptus as we approached the Golden Gate Bridge, and then the distinctive fumes of the oil refineries as we headed out of town. But now I was less alert, not so attuned to whatever existed outside the five-foot bubble in which I was running. Like a horse with blinders on, most of my attention was on the terrain under my feet. Still, I heard the wind generators south of Highway 12 at the early-morning start, and although it was pitch-dark as I ran by them, I felt their huge mechanical presence dwarfing me and the nearby cattle, which I could faintly make out as they calmly grazed below the massive, whirring blades.

Once the sun came up, the pastureland surrounding Rio Vista showed itself, golden with the fading grasses of early fall. As the sun rose higher in the sky, I felt the temperature rising, climbing to about ninety-five degrees Fahrenheit, and my crew brought me a short-sleeved shirt. Continuing on, I breathed in the dust kicked up by a dry crosswind, and with essentially no shoulder to run on, I'd flinch as the trucks whizzed by, creating vortexes of dirt and hot air that regularly ripped my hat off my head and occasionally threatened to pull me into their path. Any kind of traffic was a menace, and it became clear that one of the major dangers during this race would be the chance of getting hit. We needed to run on the highwaysâthey were legal routes and most often the shortest distance between two pointsâbut on them I felt vulnerable to the elements and the environment. Doubt made itself at home in my psyche. More than once, I wondered,

What the hell am I doing?

The thought would surface, I'd let it go, and then I'd drift back into my “road trance.”

What the hell am I doing?

The thought would surface, I'd let it go, and then I'd drift back into my “road trance.”

When a harbor seal swam by in the Sacramento River upstream from the Bay, a solitary figure cutting through the water about ninety miles inland, I felt a certain kinship with him. Some part of my brain was always looking for something to relate toâa seal, a tree, a rattlesnake, a rock. It lifted the burden somehow, knowing that others had been out of their element and suffered a private hardship, too. Yet I was hardly alone. Heather was somewhere nearby, now completely in my corner. I didn't know exactly how she'd convinced herself, but she was one hundred percent on board, working with the crew and taking shifts in the van, which always stayed within a mile of me to make sure I had everything I needed to keep going. She'd also station herself in the RV, our rolling headquarters, at mealtime and physical therapy time and bedtime, because she knew how much it meant to me just to see her face, touch her hand, lie down with her if only for a quick break.

She was indispensable to me, even though we had an all-star crew. How lucky we were to have found such experienced and expert people who were willing to take a pittance in pay and time off from their regular lives to assist me: Jesse Riley, a friend who'd run across the United States in 1997 and Australia in 1998, and directed the Trans Am '92, was a key resource to me, providing crucial insight and counseling, as he understood these megadistances. Our neighbor, Roger Kaufhold, who at the tender age of sixty-seven had climbed Kilimanjaro with me, would drive the RV and perform other countless K.P. and organizational tasks. He was invaluable not only for his services but also for his unfailingly good company, as Heather and I always felt we could be ourselves and at ease with Roger. Kathleen Kane was our massage therapist, her hands a moving balm to my legs and back. And Dr. Paul Langevin, a Wyoming orthopedist Heather and I had met at an ultrarunning training camp in Switzerland, was our doc on the road. Heather's job was to act as the “runners' advocate,” carrying Charlie's or my requests to the production crew, assisting with communications from the road, and being my chief moral support. She wasn't technically on my crew, but she was a critical member of this operation.

Five people to support me. It's one of the aspects of ultrarunning that goes against my nature, but I'd learned to accept (up to a point) that if I was going to cover the miles, I'd need help. Anytime you're going as far as we planned to go, at the pace we intended to keep, you don't just throw on a pair of shoes and head out the door. A group of people like this makes all the difference: people who understand an athlete's needs, and can anticipate them and satisfy them even before the runner recognizes there's any need at all.

Other books

Tooth and Nail by Jennifer Safrey

The Dark Tower by Stephen King

Star of the East: A Lady Emily Christmas Story by Tasha Alexander

Pretty Please (Nightmare Hall) by Diane Hoh

Nordic Lessons by Christine Edwards

Second Variety and Other Stories by Philip K. Dick

Double Tap by Lani Lynn Vale

Escape: A Stepbrother Romance Novella by Brother, Stephanie

Destroyed by the Bad Boy by Madison Collins

I, Claudia by Marilyn Todd