Running on Empty (19 page)

Authors: Marshall Ulrich

So now our crew consisted of Heather, Roger, Dave, and Brian. The next day, Kira Matukaitis, an ultrarunner some friends of ours had recommended, would join us, and we'd have a full crew again.

Â

Right around the time we reached Nebraska, I asked Heather to make a sign for the crew van: DR. PAUL'S ROLLING REHAB CLINIC.

Welcome to Nebraska!

“The Cornhusker State”

Â

Arrival date: 10/7/08 (Day 25)

Arrival time: 8:45 p.m.

Miles covered: 1,424.1

Miles to go: 1,639.1

Arrival time: 8:45 p.m.

Miles covered: 1,424.1

Miles to go: 1,639.1

I was looking for distractions again, trying to make myself and other people laugh at our situation. The truth is that I was feeling pretty miserable. After my MRI, Dr. Paul and I had agreed that I would run fifty miles, no more, the following day. We both felt that pushing too hard might aggravate my injuries, might cause a blowout that would bring everything to a halt again. Fortunately, we were routed onto a dirt road, and the softer surface was a windfall for my sore foot.

Not that I was thinking about the foot. Anything but the foot. I was caught up in memories of my childhood, my adventures, raising my kids; in missing Heather, our home in Idaho Springs, and the MKC, who were now back in their own homes. The predictable post-high depression had set in now that my family was gone. The typical symptom: what psychologists call “rumination,” my repetitive thoughts, questioning, sorting out, using the time alone as a way to review my life, my mistakes, my losses, my grief. This sadness, accompanied by busy mental processes, has been described as “exquisitely attentive to pain.” It's interesting, isn't it, that at a time when I refused to succumb to the physical pain, my mind got to work on the emotional?

We were in the grain belt, America's breadbasket. Along Nebraska's Highway 6, corn lined the road, the tall stalks providing privacy for quick bathroom breaks but not giving much of a shield against the wind, which was my new bane. Early on, it had been the heat and the dryness; we'd had a taste of rain and snow; and now came the wind, pushing at me and slowing me down, which affected the number of miles I could cover in a day. Occasionally, the air currents would come from behind and urge me forward. At those times, I'd imagine that the tailwinds carried the spirits of the four men who'd died the year before, Ted's wisdom whispering in my ear, my dad's strength buffeting my body down the road, Rory's ebullience breathing new life into my steps, Chris's adventurous spirit infusing my forward motion.

Thinking about my goals and my ghosts, I was also reflecting on the people who'd crossed the country before me. Yes, there had been other contests, like the Bunion Derby. And other runners. Plus people who'd walked it and run it solo. Even before that, pioneers had moved across it with horses and wagons, on some of the very roads I was now traveling.

WALKING ACROSS AMERICA BEFORE THE BUNIONEERS: TWO BOLD WOMEN AND AN “OLD” MAN

Helga Estby (1860â1942)

In 1893, the United States was in a panic. Speculative investing in railroads had caused overbuilding, and iffy railroad financing had resulted in bank failures, sending the country into a serious economic depression. (Sound familiar? Just substitute railroads for houses, and we saw a repeat of the same dynamic while I was running across America in 2008.) According to some sources, unemployment rates peaked in 1894 at about 18 percent, and the credit crunch affected people who'd never even been on a train, much less invested in the railroads.

Helga Estby was one of these people caught up in the domino effect of the depression, in jeopardy of losing her home and descending into poverty. Recently arrived from Norway, she'd married her husband Ole (also from Norway) in 1876, and they'd farmed and were raising eight children together in Spokane County, Washington. By 1896, they'd fallen on hard times; Ole had injured himself and couldn't work, and they couldn't pay their mortgage or back taxes.

That year, an anonymous sponsor offered $10,000 to any woman who could walk across America in seven months. It was a huge sum, comparable to about $200,000 today, and enough to save the family farm. So, desperate and defying the conventions of her timeâwomen were supposed to be weak and in need of protectionâHelga left home with her eldest daughter, eighteen-year-old Clara, and they became the first women to travel across the country without male company. In fact, they were the first people, men or women, to cross the United States on foot since the pioneers. Yet they were hardly “unprotected.” The women were packing: They were savvy country folk who knew the dangers of back roads, stayed alert to any trouble, and carried a Smith & Wesson revolver.

They arrived in New York on Christmas Eve after more than a few misadventures and averting serious danger, having nearly lost their lives in the crossing. They'd left home with only five dollars (a stipulation of the sponsors) and worked to earn money as they went. They'd faced hardship, but they'd also had kindness from the ordinary people they met along the way; most wanted to help, and supported their effort. They'd also collected autographs from prominent politicians (another stipulation) who wished them well, including President-elect William McKinley. The sponsor balked and refused to pay the prize, however, when the women missed their deadline by a couple of weeks. Penniless, Helga and Clara returned to their family farm, partway by train (on a free ticket) and partway on foot, only to discover that two of Helga's children had died of diphtheria while she was gone.

The local Norwegian-American community, including her own family, disparaged Helga for having “deserted” her husband and children, but she felt convicted about what she had tried to do. Later, she became a suffragist, and this trailblazer, who embodied stamina and self-reliance, ultimately made strides to secure women's right to vote.

Â

Â

Edward Payson Weston (1839â1929)

Â

“Weston the Pedestrian” set out in the spring of 1909 to walk from the east to the west coast, having already made a name for himself as a record breaker. His renown began nearly fifty years earlier, when he made a 453-mile trek from Boston to Washington, D.C., on a bet that he could arrive just ten days later and in time for Abraham Lincoln's inauguration in 1861. (According to a pamphlet Weston wrote, he “made no money-bets, but had wagered six half-pints of peanuts.”) While the new president prepared to address the fears of a nation now facing civil war, Weston was making his way to the capitol, too, as people cheered and bands played along the wayâ the event was sponsored and heavily publicized to defray costsâplus local eateries supplied plentiful food for free, and the townswomen gave him kisses to keep his spirits up. Perhaps distracted by all the fanfare, he arrived a day and a half late, missing Lincoln's oath of office, but the celebration surrounding Weston's arrival was so lavish that he was invited to meet the president at the inaugural ball, and Lincoln even offered to pay his way back home so he wouldn't have to return on foot. He declined; having failed the first time to arrive in ten days, as promised, he was determined to meet his goal on the return trip, which he succeeded in doing.

Years later, after the Civil War had come and gone, Weston gained greater notoriety by racking up records at a time when his sport became quite popular and the cash prizes plentiful. He cut a dashing figure; the dapper dresser smashed records and pleased crowds during walking matches staged in packed arenas. He walked one hundred miles in twenty-two hours nineteen minutes. He walked 127 miles in twenty-four hours. (Both are remarkable achievements; becoming a “Centurion,” someone who walks more than one hundred miles in less than twenty-four hours, is extraordinary.) He walked five hundred miles in six days and was crowned the Champion Pedestrian of the World.

As Weston aged, he gained strength and speed. At sixty-eight, he improved his time on a Maine-to-Chicago trek, which he'd taken forty years earlier, by twenty-nine hours. And so, at age seventy-one, he decided to walk across America, and to do it in one hundred days.

Although he was well supported financially, Weston still had to deal with the unavoidable obstacles: In the Rockies, he had to crawl because the winds were so strong; in other places, rain and snow made the going plenty miserable. He also had to battle mosquitoes, which were coming to life in the spring thaw, as well as vagabonds who harassed him. Occasionally, he was separated from his crew:

Lost

â

One automobile, one chauffeur, and one trained nurse; incidentally several suits of underclothes, three pairs of boots, dozen pairs of socks, two dozen handkerchiefs, two white garabaldis, one oilskin coat, and one straw hat. All belong to Edward Payson Weston, en route from New York to San Francisco via a devious route, over sundry obstacles, chiefly clay mud, knee deep, and still becoming deeper. Last seen on Wednesday morning in Jamestown, N.Y. When last heard of it was jammed in a mud hole between Waterford and Cambridge Springs, Penn. Thursday night with a busted engine. Any one discovering this outfit will please notify it to get a move on.

â

One automobile, one chauffeur, and one trained nurse; incidentally several suits of underclothes, three pairs of boots, dozen pairs of socks, two dozen handkerchiefs, two white garabaldis, one oilskin coat, and one straw hat. All belong to Edward Payson Weston, en route from New York to San Francisco via a devious route, over sundry obstacles, chiefly clay mud, knee deep, and still becoming deeper. Last seen on Wednesday morning in Jamestown, N.Y. When last heard of it was jammed in a mud hole between Waterford and Cambridge Springs, Penn. Thursday night with a busted engine. Any one discovering this outfit will please notify it to get a move on.

(From an article by Edward Payson Weston, special to

The New York Times,

April 3, 1909)

The New York Times,

April 3, 1909)

This must have been completely unnerving, although he apparently kept a sense of humor about it. Weston arrived in San Francisco in 104 days, and is supposed to have said that this was the worst failure of his life.

So of course he tried again. Walking from Santa Monica to New York with a goal of completing the crossing in ninety days, he finished in seventy-six. He was seventy-two years old.

Once a day, my reveries would be interrupted by the sound of a kiddie horn coming at me from behind. Charlie had rigged his mountain bike with the thing and would honk, wave at me as he rode up, peddle alongside me for a few minutes, then honk again as he sped ahead. Annoying as hell. Okay, it was kind of funny, but it was also irksome. I'm sure that's exactly what he had in mind: Most of Charlie's antics were equally humorous and irritating, and he was clearly trying to diffuse his frustration at not being able to run and truly compete with me any longer. Zipping by me on his bike, he reminded me of a preschooler who has to beat his friends at everything, even if it's meaningless.

Yet now I knew that I wouldn't stop until I was done. Charlie could ride in circles for all I cared; I was headed straight for New York City. One of the things the crew and I would say to each other all the time now, as a kind of mantra, was that we'd keep on going until we ran out of land.

8.

States of Mind

Days 27â35

Â

Â

Â

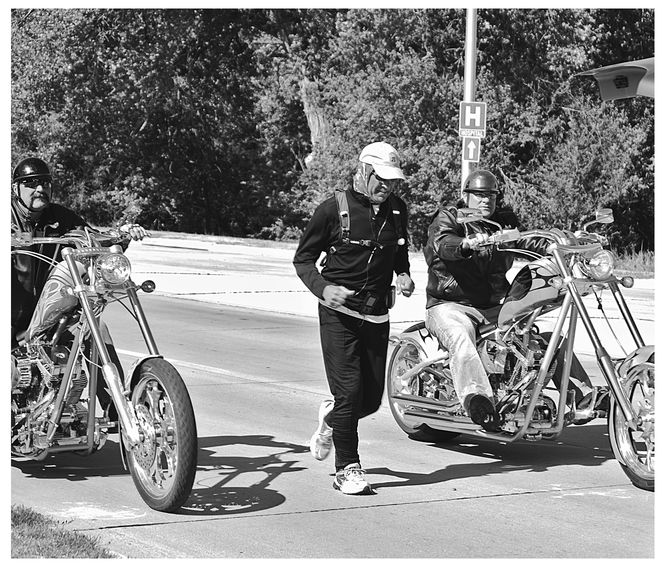

On October 9, as we arrived in the large town of McCook, Nebraska, a police escort joined us in front of the documentary production van, which was filming me and a couple of locals we'd just met, Mitch Farr and Blaine Budke, as we moved down East B Street. The attention-worthy scene: Mitch and Blaine on either side of me, riding low-slung custom motorcycles, all glistening chrome and badass paint jobs. The choppers' engines roared along, and I was amazed that Mitch and Blaine were able to go at my pace without tipping over, only about five miles per hourâfast enough for me but incredibly slow for them.

As I ran between them, the deep rumble of the engines was loud enough that I had to turn my head and yell at the easy riders to start a conversation, who quietly looked the part of leather-jacketed bikers. Blaine, who owned a hot tub company, suggested at one point that maybe I'd like to have a soak. We all laughed, knowing there was no way.

Riding along on his chopper with yellow ghost flames, Mitch offered, “If you stop long enough, I'll feed you a steak, too,” as he owns a bar and grill in McCook. Again we laughed, but I told them both I wanted rain checks.

“The next time I see you, Heather and I will be on bikes, for sure! You guys have the right ideaâriding definitely would beat running!”

They had it figured out: I wanted to see McCook and the surrounding area from the vantage of a soft seat, but still exposed to my surroundings with nothing between me and the environment. And I imagined that with my legs propped up on the foot pegs, everything would seem a damn sight more comfortable

.

.

I'd never been escorted by choppers before, and I don't imagine they'd ever ridden alongside a runner, so we all made the most of it, joking, cutting up, and teasing one another, mostly about our age, for the couple of miles we were together. Getting to know them, I formed the opinion that the next time I came through, I could count on them for anything.

Meeting and running with Mitch and Blaine energized me and also provided some colorful film footage for the documentary (which, sadly, didn't make the final cut). The producers had arranged the whole thing during their dinner at The Looking Glass the night before, and I was gratefulâjealous that they'd had Mitch's steaks, which they reported were delicious, but unreservedly grateful. Especially at this time, when I was still in a funk and doing everything I could to avoid thinking about my foot, having the opportunity to talk with a couple of guys, check out the detailing on their Big Dog and Texas choppers, hear about their local businesses, and kid around for a while was a highlight. Perks like this kept me going, put me in a better state of mind.

Other books

Claimed by the Wolf by Saranna DeWylde

Secrets of a First Daughter by Cassidy Calloway

The Paper Magician by Charlie N. Holmberg

I Lost Everything in the Post-Natal Depression by Erma Bombeck

Beauty's Beasts by Tracy Cooper-Posey

Pride and Fire by Jomarie Degioia

Cállame con un beso by Blue Jeans

Friends Like Us by Siân O'Gorman

Las palabras mágicas by Alfredo Gómez Cerdá

A Long Tall Texan Summer: Tom Walker by Diana Palmer