Running on Empty (17 page)

Authors: Marshall Ulrich

We were coming into the Great Plains, the expansive western prairie on the eastern side of the Rockies that reaches into the heartland of America. I'd be running the territory of the old bison hunters, among them the tribes of Blackfoot, Cheyenne, and Comanche, and later, Buffalo Bill and others of his ilk. We'd be in the Great Plains for the next six hundred miles, probably ten days, until we reached the NebraskaâIowa border.

Having my children with me just as this run was becoming tolerable, even fun sometimes, made me wonder if their presence was making everything better or if the contrast helped me appreciate them even more than usual. They'd arrived right as we'd left the dry heat and harsh conditions that had persisted through California, Nevada, and Utah, which seemed fitting. Each of the kids, too, had taken me through a kind of parenting desert, the years when they'd been typical teenagers, resenting authority, thinking I couldn't relate to their young lives, believing I was too strict, or too stupid, or just plain wrong. Like most kids, they'd been right, up to a point. And, like most kids, they'd seen my actions only through the prism of their inexperience and justifiably self-centered youth. But now, they were showing me how mature they'd become. I treasured every minute with the MKC, looked forward to hearing Taylor joshing with his sisters and the crew, Ali tending to business and finding ways to be useful, and Elaine trying to set a good example. It felt like being at home, and took me back to having them all within reach, where I could overhear them laughing and crying together, but mostly championing each other's causes.

Â

On the morning of day twenty-three, we expected to pass through Sterling, Colorado, but as soon as I woke up, I knew something was wrong. The plantar fasciitis was a familiar, now manageable pain, yet this was something new, excruciating and distinct. Elaine and Heather were on duty in the crew van, and they noticed how slowly I was going, especially compared with the few days before, so we switched out my shoes and Dr. Paul stretched me. Then he focused his attention on the foot, breaking up some old adhesions, making me wince and producing loud, popping noises. About two hours into the morning's run, I stopped for a fifteen-minute nap and to rest the foot again.

Soon after that, Ali and Taylor joined Elaine, and the MKC took over the crew van, although Heather and Dr. Paul stayed close. Both of them were concerned when I told them that I wanted to keep moving.

“Okay, Marsh,” Dr. Paul had agreed. “You go ahead and let me know when you've had enough.”

Within twenty minutes, Heather and Dr. Paul drove up in a car (the crew van was still a half-mile off), and I admitted that things weren't going well. At the rate I was moving, it made no sense to keep on. They picked me up and drove me forward to the Sterling emergency room, and everyone else headed to a hotel.

Because the MRI was scheduled for the next morning, I thought I should try to get a few miles in before then, but Heather insisted that if there was a fracture, running on it could cause permanent damage, and if it was another soft-tissue injury, ice and rest made a lot more sense than going out and beating up my foot, only to gain very little distance. In other words, she was trying to reason with me; she and Dr. Paul had made a secret pact to stick together and convince me. Quickly, it was obvious that she was right. We went to the hotel, too, for rest, ice, and a good meal. Who knew what tomorrow would bring?

It had been days since we'd heard anything about Charlie, but we did know that he'd set out to ride the course on a mountain bike. NEHST would continue filming his progress, and now he'd help them interview folks. Fair enough, I thought; this would allow Charlie to stay in the game to some extentâI understood his inability to give that upâbut I also wondered what had happened to our gentleman's agreement about helping the other guy if one of us dropped out. Heather and I both had a hard time seeing how Charlie's new plan fit in with an attempt to break the transcontinental running record, or a documentary called

Running America,

but that wasn't our concern.

Running America,

but that wasn't our concern.

He should be catching up to me any minute,

I thought, as he was now able to travel three or four times faster than I could, and with me laid up overnight, his progress would be even more accelerated. My drive to stay ahead of him was thwarted by both my injury and his newly acquired speed, and I chafed under the realization that, even if I could still run, he'd always be ahead of me.

I thought, as he was now able to travel three or four times faster than I could, and with me laid up overnight, his progress would be even more accelerated. My drive to stay ahead of him was thwarted by both my injury and his newly acquired speed, and I chafed under the realization that, even if I could still run, he'd always be ahead of me.

In the hotel, though, all of that seemed unimportant as I savored the time with family and the luxury of eating while sitting down. Propped up in a comfortable bed, my meal on a real, honest-to-God plate, and surrounded by family and friends, I felt like a king holding court.

Most everyone would be going home that night, so we took our time saying our good-byes. Our visit together had been so unusual, something like a breakthrough. I felt that my family really

saw

me, that even if they didn't understand what I was doing, they supported me in it unconditionally. Even my brother, Steve, who'd long ago written off running (and me, to some extentâit seemed we were constantly disagreeing about something), had come out to see us in Ault. Heather confided, too, that when she'd called my mother on her birthday, Mom had told her, “I love you,” which had brought Heather to tears. It was an unprecedented declaration, as Mom had never said that to Heather before and had even stopped saying it to me long ago. (Why? I'm not sure, maybe something to do with my stubbornness, or my own reserve. I think both of us had forgotten that staying connected was more important than anything else.) It signaled a significant change, and Heather and I held each other, crying with joy. At the time, I had a hard time taking it all in, but I felt incredibly grateful for every subtle and positive transformation.

saw

me, that even if they didn't understand what I was doing, they supported me in it unconditionally. Even my brother, Steve, who'd long ago written off running (and me, to some extentâit seemed we were constantly disagreeing about something), had come out to see us in Ault. Heather confided, too, that when she'd called my mother on her birthday, Mom had told her, “I love you,” which had brought Heather to tears. It was an unprecedented declaration, as Mom had never said that to Heather before and had even stopped saying it to me long ago. (Why? I'm not sure, maybe something to do with my stubbornness, or my own reserve. I think both of us had forgotten that staying connected was more important than anything else.) It signaled a significant change, and Heather and I held each other, crying with joy. At the time, I had a hard time taking it all in, but I felt incredibly grateful for every subtle and positive transformation.

Once everyone left the room, I showered and tucked in for the night while Heather got up every two hours to ice my injuries. When I awoke the next morning, I was pretty well rested, although Heather was now fatigued from many, many days of interrupted, short sleep. In the waiting room at the hospital, I grabbed a newspaper, another simple pleasure to enjoy. This was the first thing I'd read, other than food wrappers, in three weeks. The October 6, 2008, morning headlines clued me in, for the first time, about how the U.S. presidential race was shaping up (“Palin Accuses Obama of âPalling Around' with Terrorists”), and how serious the financial crisis had become (“Dow Jones Industrial Average in Freefall”). It made me glad I hadn't been paying any attention to the nasty politics or depressing national news, and my only indicators of what was happening in the “real world” had been the fluctuations I'd seen on the gas station price signs. This week, I'd noticed, you could fill up for about $3.50 a gallon, down about 10 cents from the week before and almost a buck and a half cheaper than it had been in California at the start of our run.

After a short time in the waiting room, a nurse came to prep me for the MRI, and the whole procedure was over quickly. The day before, I'd told Heather that if the doctors found soft tissue injuries, I'd be continuing. If they found a stress fracture, I insisted, I'd get a walking cast and still keep going. Either way, I wasn't stopping. But Dr. Paul and Heather had other ideas, which they'd discussed privately and didn't share with me: They simply wouldn't support me going forward with a broken bone, risking permanent damage that would prevent me from ever running or mountaineering again. Although they were able to look at the big picture, think ahead to the future, I was not: My world was this run, right now. They were doing their job, looking out for my long-term interests, and I was doing my job, focusing on finishing this race, no matter what. We'd know soon if our interests would collide.

Â

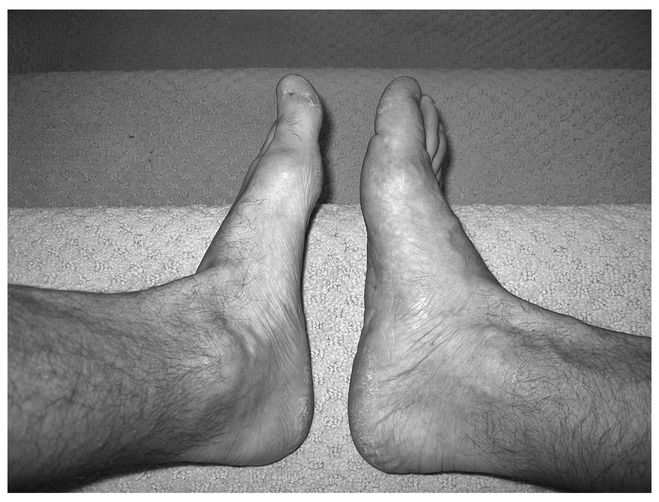

The doctor reported that I had muscle strain and tendonitis, including micro tears in the muscles of my foot and a longitudinal tear within the tendon of the outside of my right foot. There was no evidence of a stress fracture.

Would the pain eventually abate if I continued running?

The doctor assured me that, no, it wouldn't. So I asked what he recommended for treatment, and he suggested the usual runner's remedy: rest, ice, and elevation, plus an anti-inflammatory, like ibuprofen, to help with the swelling.

Rest? The last three I could definitely do (sometimes), but how would I manage that first one and still run the remaining 1,700 miles?

After a long pause, I quipped my counteroffer: If I ran only forty miles a day, instead of sixty, would that constitute rest?

The look on his face was priceless. At first, he laughed, but then his smile collapsed as he recognized that although I thought I was being funny, I was also totally serious about the mileage. He must have thought I was nuts. Heather has remarked since that his reaction was a second dose of reality; we'd been so cocooned in our own world that not only were we unaware of our country's current events, but we'd forgotten how crazy our own situation sounded.

I'm running across the United States, see, and I've already come over thirteen hundred miles, you know, and even though Charlie dropped out (he's bicycling now),

somebody's

got to keep running to the finish, and I don't give up when I've said I'm going to do something. I've been dreaming of doing this for years, and so even though this is going to be incredibly painful to run on these injuries, I want to keep going, so can I just cut back to forty miles a dayâwould that be all right?

somebody's

got to keep running to the finish, and I don't give up when I've said I'm going to do something. I've been dreaming of doing this for years, and so even though this is going to be incredibly painful to run on these injuries, I want to keep going, so can I just cut back to forty miles a dayâwould that be all right?

Yeah, I'm pretty sure he thought I was nuts.

7.

This Is Not My Foot

Days 25â26

Â

Â

Â

In 1928, when the bunioneers ran the first organized footrace across the United States, they'd been promised a winner's purse of $25,000, big money in those daysâand no small sum for two months of work, even by today's standards. The race's founder, Charles C. Pyle, could be called the Depression-era Don King, the top sports promoter in his time. He'd dangled the money to lure big-name athletes, and offered decent, free food and lodging to all comers, which pulled another pool of men who hadn't yet claimed either fame or fortune, who either aspired to greatness, craved adventure, or needed a roof over their heads. They ran most of the way on Route 66, the Mother Road that stretched from Los Angeles to Chicago, most of which was still unpaved after two years under construction.

Good ol' Charley didn't exactly come through. Sure, a few days after the end of the race, he awarded the prize money to twenty-year-old Andy Payne, who came in first with an average pace of ten minutes per mile and completed the 3,400 miles from California to New York in 573 hours: he finished 84 stages, averaging forty miles per day.

But along the way, conditions were deplorable. Charley provided cold showers, scant food, and drafty quarters . . . some of the time. Men of means supplemented what they were given, but those who didn't have the money to buy extra food or other necessities made do with the meager provisions as best they could. It's possible that Charley (also nicknamed C. C. for “Cash and Carry”) had always meant to skimp, but it's more likely that he just didn't understand what it would take to properly care for his runners as they raced across the country. Logistically, ultrarunning is like a cross between orienteering, camping, and a military march. Unless you've done it before, there's no way you can know what will be required, from how much food you'll need to where your runners will relieve themselves. Not only do you have to deal with the anticipated requirements to keep everyone on the move, but you also have to contend with the unanticipated, whatever special circumstances come up and demand that you forget your plans and wing it. From what I know of the Bunion Derbies, neither the expected nor the unexpected was handled very well.

The bunioneers' route (rough as it was) had been scouted, a race doc was on hand, and Charley had also hired a cobbler to fix runners' shoes when they fell apart, but their accommodations were nowhere near as fine as mine. What I hadâoccasional access to a toilet, a warm bed every night (even if it was most times in an RV that Heather and I shared with three other people), regular showers, clean clothes, gear and gizmos from sponsors to boost my performance and relieve my pain, Dr. Paul to “fix” me and Kathleen to massage me when I needed it, my wife to care for and comfort me, and about eight thousand to ten thousand calories a dayâwould have seemed like royal treatment to the men who ran in the Bunion Derby. Contrast these things with the bunioneers' sketchy lodgings, the nearly complete lack of facilities for personal hygiene, and the unappetizing fare. Sometimes they slept in barns, or on the floors in post offices and jailsâand those were some of the better accommodations. More than a few of these men fueled their efforts with a single pot of beans every day. Then consider that the black men in the race were harangued, especially in the segregated South. In Texas, by law, blacks weren't allowed to share quarters with whites, so they bedded down wherever they couldâbut not in hotels, because none would take them in even if Charley had offered to pay.

Other books

Cato 05 - The Eagles Prey by Simon Scarrow

You Will Never Find Me by Robert Wilson

Seducing Celestine by Amarinda Jones

Amos's Killer Concert Caper by Gary Paulsen

Taken by the Tycoon by Normandie Alleman

Origin Exposed: Descended of Dragons, Book 2 by Jen Crane

A Natural History of the Senses by Diane Ackerman

Love's First Flames (Banished Saga, 0.5) by Ramona Flightner

On Trails by Robert Moor

One Hot Summer Anthology by Morris , Stephanie