Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation (49 page)

Read Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation Online

Authors: Sean Bodmer

Tags: #General, #security, #Computers

One of the most direct instances of obtaining evidence through social exchange was the compromise of a honeypot

10

(run by a member of the Honeynet Project

11

) by a malicious online actor some years ago. Once he had compromised the server, he established IRC server services and then opened a video connection to another online actor. He proceeded to brag about having just “owned” this particular machine. What he was not aware of was that the compromised server had alerted security researchers to the intrusion, and the researchers had tapped into the honeypot machine to monitor the video conversation taking place between the offender and his colleague. Unfortunately, word of the compromise and video feed spread quickly throughout the organization’s security team, and soon there were a number of additional information security team members watching the video via new monitoring channels. This resulted in seriously reducing the performance of the compromised machine. The offender noticed the slow response of his newly captured prize and investigated its cause, which resulted in him fleeing the honeypot. Thus, while a very rich and useful evidence trail was generated by the attacker, in the end, the fascination of observing this evidence-rich live video feed led to the end of this evidence trail.

The fact that online malicious actors are social actors who communicate with each other also has some beneficial effects on building a schema of their friends and accomplices. Holt and others analyzed the LiveJournal entries for 578 Russian hackers across seven hacking cyber gangs (Holt et al, 2009). They examined who had “friended” whom on their journal pages and counted LiveJournal communications among all the individuals for an extended period of time.

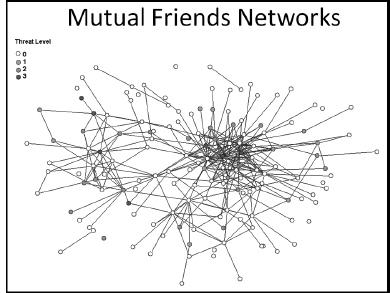

Organizing the resulting data into a social network framework, Holt and his colleagues were able to draw a fairly detailed picture of friendship ties and communications volumetrics among the hackers. The social network diagrams they produced from the data revealed which individuals were at the center of the hacking gang and which ones were isolated at the periphery of the network. They were also able to identify the communication paths between the hacking groups to see which groups were more closely communicating with each other. Finally, they rated each of the hackers in terms of the level of threat they posed to the online community. Threat levels varied from no real threat (0) to high-level threat (3). They then proceeded to analyze the mutual friendship network using threat-level descriptors. The results of this analysis are illustrated in

Figure 4-2

.

Figure 4-2

Russian hacking gangs mutual friend network by threat level (Holt et al, 2009)

In

Figure 4-2

, notice that there are two distinct groupings of high-threat individuals. The first grouping is near the center of the social network diagram and reveals three high-threat individuals with a very large number of friendship connections. You might label these actors central high-threat actors. If you regarded these individuals as elements of a potential suspect pool, you can see that there are a lot of individuals who know them and may be either unwitting or cooperating sources of information about these high-threat individuals.

Toward the left side of the mutual friends network, you see one additional high-threat individual who also has the characteristics, although to a smaller extent, of being a central high-threat actor. The remaining three individuals on the left side of the network diagram are much more social isolates. Because of the paucity of mutual friendship ties, it is going to be more difficult to obtain useful information about these individuals. If they have purposely isolated themselves from others socially to avoid detection by the authorities, then they may pose the greatest risk.

There is insufficient space to catalog all of the potential social communications and connections that may be useful to the profiler in gathering additional information and developing a more effective profile. Personal websites of potential offenders, attendance at hacking conferences (including giving talks and presentations), graphic images that may contain special meaning for the offender, and many other socially meaningful pieces of information are all present on the Web for collection and analysis by the cyber profiler.

There are many additional analytical approaches to using available online offender data, such as psycholingustic analyses of chats or website postings. More discussion about the analysis and utilization of socially meaningful communications and connections will be presented in

Chapter 10

.

Conclusion

The objective of this chapter has been to introduce you to the history, principles, logic, limitations, and challenges to psychological and behavioral profiling. Where possible, the discussion has forked into two threads: the first one summarizing the traditional criminal profiling aspect of the subject, and the second extending that discussion to the field of cyber profiling.

This chapter also briefly summarized some of the more recent efforts that have been aimed at providing a better understanding of the motivations and behaviors of online malicious actors, often through the use of taxonomies. The objective of these summaries is not to provide you with a complete understanding of the research, but rather to point you to a number of prominent and recent research efforts that can serve as references for further study and utility.

The final part of this chapter dealt with some of the key information vectors that are relevant to the development of an effective profile. Again, the purpose of discussing these vectors is not to provide a complete compendium of knowledge about each one, but rather to point you in fruitful directions regarding the successful application of these data points to criminal- and/or intelligence-driven objectives.

References

Berger, J. Fisek, M., Norman, R. and M. Zelditch, Jr. (1977). Expectation States Theory: A Theoretical Research Program. Cambridge, Winthrop.

Bongardt, S. (2010). “An introduction to the behavioral profiling of computer network intrusions,”

Forensic Examiner

.

Canter, D. (1994). Criminal Shadows. London: Sage.

Canter, D. (2004). “Offender Profiling and Investigative Psychology.” Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling,1: 1–15.

Canter, D. and Alison, L. (2000). Profiling Property Crime. In D. Canter and L. Allyson, eds., Profiling Property Crime. Aldershot, Englind: Ashgate Publishing.

Canter, D. and Larkin, P. (1993). “The Environmental Range of Serial Rapists.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, 13: 63–69.

Chiesa, R., Ducci, S., and S. Ciappi. (2009). Profiling Hackers: The Science of Criminal Profiling as Applied to the World of Hacking. Boca Raton: Auerbach Publishing.

Denevi, D. and Campbell, J. (2004). Into the Minds of Madmen: How the FBI Behavioral Science Unit Revolutionized Crime Investigation. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

Douglas, J. (1995). Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit. New York: Scribner.

Douglas, J. and M. Olshaker. (1999). “The Anatomy of Motive: The FBI’s Legendary Mindhunter Explores the Key to Understanding and Catching Violent Criminals.” New York: Scribner.

Douglas, J., Burgess, A., Burgess, A. and R., Kessler. (2006). Crime Classification Manual: A Standard System for Investigating and Classifying Violent Crimes. Second Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

FBI BAU-2. (2005). Serial Murder: Multi-disciplinary Perspectives for Investigators. Federal Bureau of Investigation, R. Morton editor.

Florence, J. and R. Friedman. (2010). Profiles in Terror: A Legal Framework for the Behavioral Profiling Paradigm. George Mason University Law Review 17: 423–481.

Hazelwood, R. and Douglas, J. (1980). “The Lust Murder.” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin 49: 18–22.

Hazelwood, R. and S. Michaud. (2001). Dark Dreams: Sexual Violence, and the Criminal Mind. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Hechter, M., and Horne, C. (2009).

Theories of Social Order

(second ed.). Palo Alto: Stanford University.

Hollinger, R. (2001). “Computer Crime,”

Encyclopedia of Crime and Delinquency

(Vol. II, pp. 76–81). Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis.

Holt, T., and Kilger, M. (2008). “Techcrafters and Makecrafters: A Comparison of Two Populations of Hackers,”

2008 WOMBAT Workshop on Information Security Threats Data Collection and Sharing

(pp. 67–78). Amsterdam.

Holt, T., Kilger, M., Strumsky, D., & O. Smirnova. (2009). “Identifying, Exploring, and Predicting Threats in the Russian Hacker Community”. Presented at the Defcon 17 Convention, Las Vegas, Nevada.

Kilger, M. (1994). “The Digital Individual.”

The Information Society

, volume 10:93–99.

Kilger, M., Stutzman, J., and O. Arkin, (2004). Profiling. In The Honeynet Project Know Your Enemy. Addison Wesley Professional (pp. 505–556).

Kilger, M. (2010). “Social Dynamics and the Future of Technology-driven Crime. In T. Holt and B. Schell (Eds.), Corporate Hacking and Technology Driven Crime: Social Dynamics and Implications (pp. 205-227). Hershey, PA: IGI-Global.

Kretschmer, E. (1925), Physique and Character. New York: Harcourt Brace.

La Fon D. (2008). The Psychological Autopsy. Pp. 419–430 in B. Turvey, editor, Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis. Burlington, MA: Academic Press.

Lombroso, C. (2006).

Criminal Man

. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mead, G. (1932). The Philosophy of the Present. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

Mead, G. (1934). Mind, Self and Society. Charles Morris, editor. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Meyers, C., Powers, S. and D. Faissol. (2009). Taxonomies of Cyberadversaries and Attacks: A Survey of Incidents and Approaches. Lawerence Livermore National Laboratory Report LLNL-TR-419041, April, 2009.

Nakashima, E. (2007). “A Story of Surveillance.” Washington Post, November 7, 2007. Retrieved from

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/11/07/AR2007110700006.html

on April 29, 2012.

Parker, D. (1976).

Crime by Computer

. New York: Scribner.

Parker, T., Shaw, E., Stroz, E., Devost, M., and Sachs, M. (2004).

Cyber Adversary Characterization: Auditing the Hacker Mind

. Rockland, MA: Syngress.

Petherick, W. (2009). Serial Crime: Theoretical and Practical Issues in Behavioral Profiling. Second edition. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press.

Petherick, W. and Turvey (2008:). Forensic Victimology: Examining Violent Crime Victims in Investigative and Legal Contexts. Burlington, MA: Academic Press.

Poindexter, J. (2002). Remarks delivered at

DARPATech

2002 Conference, Anaheim, Calif., August 2.

Rengert, G., Piquero B. , A. and P. Jones. (1999). “Distance Decay Reexamined.” Criminology 37: 427–446.

Ressler, R., Burgess, A. and J. Douglas (1992). Sexual Homicide: Patterns and Motives. New York: Free Press.