Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation (47 page)

Read Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation Online

Authors: Sean Bodmer

Tags: #General, #security, #Computers

Another traditional profiling technique involves constructing a psychological autopsy where a timeline of major stressors in the victim’s life may be useful in understanding how the individual came to be a crime victim (La Fon, 2008):

Often a timeline is constructed in the course of a psychological autopsy in murder cases that depicts major life stressors (financial problems, losses such as of employment or loved ones, substance abuses), psychological states, and major life events (birthdays, marriages, etc.). Psychological theory is applied to this data to develop a conceptualization of the victim’s personality as well as a psychosocial environment of the deceased preceding death.

In both criminal profiling and cyber profiling, the time of the crime itself is an important factor. In traditional criminal profiling, the time of day has a number of characteristics that may be important to developing the profile. Was the crime committed during the day or during nighttime hours? Was it a time of day when there would be a lot of other people around, or was it a more quiet time of the day or night? How does the time of day interact with the environment where the crime was committed? Was it normal for the victim to be in the environment at the time of the crime? If not, then something or someone probably performed some action that motivated the victim to depart from his usual schedule and transit to the crime scene. These and many more questions can provide clues to the profiler to understand the victim’s actions better, and therefore produce a better understanding and profile of the offender.

In cyber crime, the time of the crime also can play an important part in the development of an offender profile, but there are some significant differences from its role in traditional criminal profiling. One of the more obvious differences is the fact that many times (with the exception sometimes of insider cyber crimes), the victim and the perpetrator are not in the same geographical location—sometimes not even on the same continent. While this fact has often been played up, especially in the media, this geographical discontinuity means that there may also be crucial temporal clues associated with the cyber crime. Common activities such as work, school, rest, sleep, and recreation often occur at specific, nonrandom parts of the day, allowing the investigator to be able to infer an approximate geographical location for the offender according to the time of the cyber attack.

7

While this approach may only suggest a very rough idea of where the offender might be, remember that the strategy of profiling is to narrow down the pool of potential suspects.

It’s important to gain an understanding of when the offender might be active in order to gather more information about the potential identity and motives of the attacker. Participating in attacks is not the only activity that offenders engage in online. They are also very likely to participate in chat rooms where details of their exploits, including the one in question, may be disclosed or discussed. If it’s suspected that the offender participates in chats with others in a specific chat forum at a specific time, then a profiler who wishes to take a more proactive approach may attempt to gain entrance to the forum and log in during the time the offender may be present. Being able to monitor the discussions at hand, as well as engage the suspected offender in conversation, gives the profiler the opportunity to elicit more details from the offender and evaluate them against the current profile and evidence at hand.

Geolocation

Geographic details are another emerging information vector for profiling. A new area of expertise in geoprofiling has begun to emerge as a key player in the analysis of crime scenes and the identification of an offender.

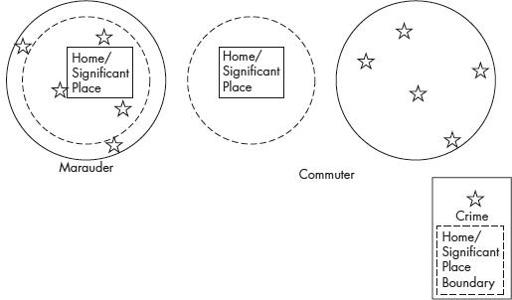

Early efforts in linking geography to criminal activity include David Canter and Paul Larkin’s circle theory (Canter and Larkin, 1993). This theory suggested that the offender committed crimes within a specific circle that had a relationship to a place of significance for the offender. This place of significance was not necessarily the offender’s home. They hypothesized that there were two types of offenders:

Marauder

Marauders were assumed to travel a distance from their place of significance before committing their crime. Thus, you could draw a circle around the crimes and assume that the offender’s place of significance would lie somewhere near the center of the circle.

Commuter

Commuters travel a specific distance away from their place of significance and then commit crimes in a specific area some distance away.

Figure 4-1

illustrates the geospatial relationship between marauder and commuter criminal types. While interesting, the circle theory has a number of flaws, including not taking into account important geographic, density, and transportation features of the city, suburb, or rural area.

Figure 4-1

Canter and Larkin’s marauder and commuter criminal types

Another fairly simplistic theory put forth by Kim Rossmo (2000), called the least effort theory, suggests that when criminals evaluate multiple areas for committing crimes, they take into account the amount of effort necessary to travel there, and often pick the area that takes the least amount of effort and resources to reach. A variation of that is the idea of distance decay, where offenders will commit fewer and fewer crimes the farther they travel from their home (Rengert et al, 1999). Rossmo also comments on Rengert’s theory by suggesting that, around the offender’s home or place of significance, there is a “buffer zone” within which the offender would avoid committing offenses.

A lot of attention has been paid to the fact that the Internet has enabled individuals and groups to attack others who are geographically distant from them. In particular, the media has emphasized this particular characteristic to a great extent and lamented that this has made pursuit and prosecution nearly impossible. While it is quite true that the elimination of propinquity as a prerequisite to criminal activity has made the investigation of cyber crime more difficult, what we really want to read from this is that the rules of the game have changed for the deployment of geographic information in cyber profiling.

One thing that must not be forgotten in the popular debate of the issue is that it is certain that at a specific point in time, an offender is going to exist in a unique geographical location. Remember that often the ultimate purpose of producing a cyber profile is the physical apprehension of the perpetrator, just as when traditional criminal profiles are employed. To physically apprehend the perpetrator means that you must be able to identify his geographic location at some specific moment where law enforcement officials can be also be collocated, so that the offender can be arrested and detained. Thus, the extent to which profilers can use geographic information to locate offenders can facilitate the eventual physical apprehension of the suspects.

Notice that I used the word “often” in discussing the ultimate goal of the cyber profile. This may not always be the way in which geographic information is put to use. It may be the case that it is sufficient to identify a general area (country, region of a country, and so on) where the offender is likely to reside. Knowing the offender lives in a specific geographical region increases the likelihood that the investigators can identify the offender’s ethnic or cultural origins. This information may play an important part in the strategic approach that the defenders or investigators deploy by increasing the probability of success in engaging offenders in multiple discussions and generating rapport with them, in hopes of getting them to disclose further information about themselves, their activities, and their associates. Playing on ethnic or nationalistic sympathies is one way in which geographic information provided by the profiler may assist investigators.

Skill

Skill is one of the more important information vectors for both traditional and cyber profilers. Skill level is not only a key component to the potential identification of the offender, but also is an important indicator of the level of threat the offender poses to the general population. In traditional criminal profiling, there may be crime scene evidence of a specific skill. For example, the method with which a body was carved up might indicate medical knowledge, or the manner in which a person was killed may indicate that the perpetrator knew something about efficient methods of killing, suggesting that the offender had military training.

Skill may also be present in traditional crime scenes in the form of a lack of evidence. As criminals gain skill and expertise at their particular crime, they often learn to leave behind fewer potential pieces of evidence. Career criminals are likely to remain nonincarcerated career criminals only if they become more expert at minimizing the number and quality of evidence left at the crime scene.

Skill level in the world of cyber crime perhaps plays an even more important part than in the traditional criminal profiling arena. The level of skill at hacking and exploiting networks, servers, routers, computers, operating systems, and applications has a direct correlation with the magnitude of threat that the offender poses. Individuals with low levels of skill generally must rely on a rudimentary, self-authored exploit or virus code, or they need to use developed exploit kits or tools, which are likely to be known or to become known in the near future. As a result, defenses are developed to attenuate the threats that they pose. Individuals with a high level of skill in a number of areas are able to develop new exploits that are difficult to defend against. Two examples of such threats are polymorphic viruses and intelligent malware that avoid discovery by security applications active on servers and networks.

As is the case with expertise levels in any sort of skilled profession, the frequency distribution of individuals by level of skill is not uniform, but rather usually some sort of exponentially decreasing function that results in a large number of individuals at the low-risk end of the threat spectrum and a very small number of individuals at the high-risk end of the distribution. This is one reason why skill level has been prominently featured in some of the cyber-profiling and cyber-crime literature as witnessed by the work of Marc Rogers (Rogers, 2005 and 2010) and Raoul Chisea and his colleagues (Chisea et al, 2009). In addition, Carol Meyers and her collaborators have developed a taxonomy of offenders that uses skill as a primary classification criterion, with level of maliciousness, motivation, and method as secondary characteristics (Meyers et al, 2009). Thus skill level will be one of the key attributes discussed in more detail in

Chapter 10

, given its power to discriminate among members within specific pools of malicious actors.

Motivation

Motivation has been a central theme in traditional criminal investigations, and logically has historically been a significant factor in violent criminal profiling. Many of the early pioneers and practitioners of criminal profiling, such as John Douglas (Douglas, 1995 and Douglas and Olshaker, 1999) and Roy Hazelwood (Hazelwood and Michaud, 2001), spend time exploring the various motivations for serial killers, serial rapists, and other types of violent criminals. The motivation of the offenders plays an important role in a number of key facets of crime, including victim selection, the nature of the crime itself, the level of violence employed, and clues to the psychological makeup of the offender.