Red Capitalism (7 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

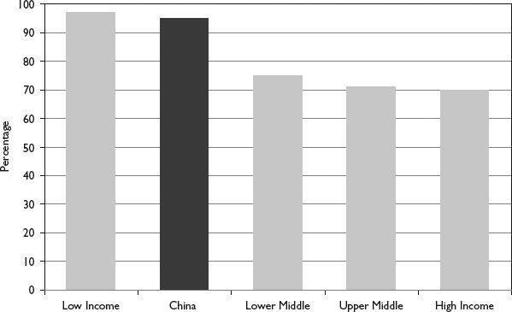

Such a concentration of financial assets in the banking system is typical of most low-income economies (see

Figure 2.1

).

1

What differs in China’s case, however, is that the central government has unshakable control of the sector. Foreign banks hold, at best, little more than two percent of total financial assets (and only 1.7 percent after the lending binge of 2009), as compared to nearly 37 percent in the international lower-income group. This will not change anytime soon. A very senior Chinese banker was asked in early 2010 about the government’s strategy for foreign banks and where the foreign sector would be in five years. He replied after some thought: “I don’t believe anyone has thought much about this; I expect that in five years’ time, foreign bank assets will constitute perhaps two or three percent of total bank assets.” Despite the undeniable economic opening of the past 30 years and the WTO Agreement notwithstanding, China’s financial sector remains overwhelmingly in Beijing’s hands. There appears to be little political acceptance of the need to diversify the holders of financial risk.

FIGURE 2.1

Concentration of banking assets by country income group

Source: Data from 150 countries; based on Demirguc-Kunt and Levine (2004): 28

If one looks at incremental capital raising, it is obvious the stock markets in Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Shanghai are an afterthought. It is bank lending and bond issuance that keep the engine of China’s state-owned economy revving at high speed. For example, 2007 was a record year for Chinese equity financing: more than US$123 billion was raised, but in the same year, banks extended new loans totaling US$530 billion and debt issues in the bond market accounted for another US$581 billion. In the past decade, equity as a percentage of total capital raised has been measured in the single digits as compared with loans and debt. Who underwrites and holds all that fixed-income debt? Banks hold over 70 percent of all bonds, including those issued by the MOF (see Chapter 4). Taking this a bit further, in the stock markets as well, the huge deposits placed by institutional investors seeking share allocations in the primary market are also funded by loans from banks. In China, the banks are everything. The Party knows it, and uses them as both its weapon and its shield.

CRISIS: THE STIMULUS TO BANK REFORM, 1988 AND 1998

Today’s banking system is the child of the financial crises that began China’s 30 years of reform and ended each of its next two decades. At the close of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, there were no banks or any other institutions left functioning. Beijing faced the challenge of institutional design and it was natural that it fell back on traditional Soviet-inspired arrangements. These can be described roughly as a Big Budget, the MOF, and small banks that did little more than lend short-term money. Nor was there an important role for a central bank. Most important of all, the key management of the banks was not centrally controlled by Beijing, but by provincial Party committees (the local Party always needs money). Over the course of the 1980s, this arrangement built up into a lending spree that ended in inflation, corruption and near civil war in 1989. In 1992, the Party, fired up by Deng Xiaoping’s words in Shenzhen, took the economy and its banking system straight back to where it had been in 1988. There were spectacular bubbles and busts, most notably the Great Hainan Real Estate Bust of 1993 (outlined later in this chapter).

In line with its decision in 1990 to try out capitalist-inspired stock markets, in 1994, Beijing abandoned the Soviet banking model in favor of one based largely on the experience of the United States. New banking laws and accounting regulations, an independent central bank, and the transformation of the four state banks into commercial banks all followed. Three policy banks were established to hold non-commercial loans. This effort, however, was stillborn, sidetracked by Zhu Rongji’s greater priority to bring the country’s raging inflation under control. It took the Asian Financial Crisis and the collapse of GITIC in 1998 to catalyze a sustained effort to transform the banks along the lines of the framework adopted in 1994.

China’s leaders, no matter who they were or are, know that the country’s financial institutions are the source of the greatest threat to financial and social stability. They differ significantly, however, over how to minimize this threat. The traditional impulse of the Party has always been toward crude outright control. For the banking system, this has meant an absence of control and the creation of new crises. Realizing this, Zhu Rongji and his team adopted a more sophisticated approach from 1998. Much as they did in reforming the SOEs, this team sought to create a more independent banking system by adopting international methods of corporate governance and risk management. Once this was in place, the key decision was to submit the whole to the scrutiny of international regulators, auditors, investors and law by listing the banks in Hong Kong rather than in Shanghai. The experience of China’s banks in the 1980s and 1990s shows why Zhu would seek such an approach and also sheds light on bank behavior in 2009.

The expansive 1980s

In 1977, China was bankrupt; its commercial and political institutions in tatters. There was no real national economy, only a collection of local fiefdoms held together by a broken Party organization. What strategy could be used to pull it all back together? Looking back to the 1949 revolution, China had sought to create a central planning system with the assistance of Soviet advisors in the 1950s. But, parsing those years between 1950 and the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957, only a start had been made. From 1957 to 1962, Mao Zedong threw China into its first prolonged period of disorder and invited all Russians advisors to go home. Pushed aside when the heavy costs of the Great Leap Forward were totaled up, Mao quickly made his comeback and, in 1966, threw the country into chaos for a further 10 years.

Under such chaotic circumstances, how much of a government, much less any planning system, really could have been put in place? Whatever the answer, there was no banking system when the Gang of Four was deposed in 1976; everything had to be rebuilt and the only model anyone knew of was based on blueprints the Soviet advisors had left behind. At the start of the reform era in 1978, there was only one bank, the PBOC, and it was a department buried inside the MOF. From this small group of only 80 staff, a great burst of institution building began.

New banks and non-bank financial entities proliferated wildly in the government’s enthusiasm for what it saw then as financial modernization (see

Table 2.2

). By 1988, there were 20 banking institutions, 745 trust and investment companies, 34 securities companies, 180 pawn shops and an unknowable number of finance companies spread haphazardly across the nation. Every level of government succeeded in establishing its own set of financial entities, just as they have now set up “financing platforms” of every kind. It was as if money could be conjured up simply by hanging up a signboard with “financial” on it.

TABLE 2.2

The proliferation of financial institutions in the 1980s

| Type and number of institution | Date founded | |

| 1) | 20 banking institutions including: | |

| People’s Bank of China | January 1978 | |

| Bank of China | January 1978 | |

| People’s Construction Bank of China | August 1978 | |

| Agricultural Bank of China | March 1979 | |

| Industrial and Commercial Bank of China | January 1984 | |

| China Investment Bank | April 1994 | |

| Xiamen International Bank | December 1985 | |

| Postal Savings | January 1986 | |

| Ka Wah Bank | April 1986 | |

| Urban Credit Cooperatives | July 1986 | |

| Aijian Bank and Trust Co. | August 1986 | |

| Wenzhou Lucheng Urban Credit Cooperative | November 1986 | |

| Bank of Communications | April 1987 | |

| China Merchants Bank | April 1987 | |

| CITIC Industrial Bank | September 1987 | |

| Yantai Housing and Savings Bank | December 1987 | |

| Shenzhen Development Bank | December 1987 | |

| Fengfu Housing and Savings Bank | December 1987 | |

| Fujian Industrial Bank | August 1988 | |

| Guangdong Development Bank | September 1988 | |

| 2) | 745 trust and investment companies including: | |

| China International Trust & Investment Corp. | October 1979 | |

| ICBC Trust | April 1986 | |

| Shenyang Municipal Trust & Investment Co. | August 1986 | |

| China Agricultural Trust & Investment Corp. | 1988 | |

| Bank of China Trust & Investment Co. | 1988 | |

| China Economic Development Trust | 1988 | |

| Guangdong International Trust & Investment Co. | December 1980 | |

| 3) | 34 securities companies | 1988 |

| 4) | 180 pawn shops | from 1984 |

| 5) | an unknown number of finance companies | from 1984 |

At such an early stage of revival, and lacking any professional staff, banks could hardly be anything other than an appendage of the Party organization and the Party did not understand how to use the banks. This can be seen in the mission statement devised by the government for banks: “The central bank and the specialized banks should take as their objective economic development, currency stability and increasing social productivity.” This statement juxtaposed economic growth with a stable currency, but in the Party’s hands, the former will always win out. More critically, there was a basic flaw in institutional design: the banks were organized in line with the government administrative system. Although the PBOC may have been a part of the State Council in Beijing, its key operational offices were at the provincial level and here they were subordinate to local Party committees. Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, the local Party controlled the appointment of the senior PBOC branch managers as well as those of the other banks. Of course, the preference of the local government will always be for growth and easy access to money. As the consequent raging inflation in the late 1980s attested, combining poorly trained staff with political enthusiasm was tantamount to playing with fire.

Just as in 2009, these institutions loaned out money unstintingly so that by the late 1980s, inflation officially reached nearly 20 percent (see

Figure 2.2

). As administrative controls were imposed, there began to be runs on local bank branches. Inflation, corruption and lack of leadership experience eventually led to the events of 1989. After the crackdown of 1989 and 1990, the whole thing began again: a few speeches by Deng Xiaoping in Guangdong in early 1992 and the financial system ran out of control. The Great Hainan Real Estate Bust provides an illustration of just what this means.

FIGURE 2.2

Inflation vs. loan growth, 1981–1991