Red Capitalism (2 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

So the modern age of technology provided all the dots that, linked together, present a picture of the financial sector. How they are connected in this book is purely the authors’ collective responsibility: the picture presented, we believe, is accurate to the best of our professional and personal experience. We hope that this book will, like

Privatizing China

, be seen as a constructive outsiders’ view of how China’s leadership over the years has put together what we believe to be a very fragile financial system.

For all the fragility of the current system, however, one of us is always reminded that his journey in China began in Beijing back in 1979 when the city looked a lot like Pyongyang. With North Korea in the headlines again for all the wrong reasons, it is worth remembering and acknowledging the tremendous benefits the great majority of Chinese have reaped as a result of the changes over the past 30 years. This can never be forgotten, but it should also not be used as an excuse to ignore or downplay the very real weaknesses lying at the heart of the financial system.

We would like to thank those who have helped us think about this big topic, including in no particular order Kjeld Erik Brosdgaard, Peter Nolan, Josh Cheng, Jean Oi, Michael Harris, Arthur Kroeber, Andrew Zhang, Alan Ho, Andy Walder, Sarah Eaton, Elaine La Roche and Victor Shih. Over the years we have grown to greatly appreciate our friends at John Wiley, starting with Nick Wallwork, our publisher who kickstarted our writing career in 2003, Fiona Wong, Jules Yap, Cynthia Mak and Camy Boey. Professionals all, they made working on this book easy and enjoyable. John Owen was an unbelievably quick copyeditor and Celine Tng, our proofreader, gave “detail-oriented” a whole new definition! We thank you all for your strong support. What we have written here, however, remains our sole responsibility and reflects neither the views of our friends and colleagues, nor those of the organizations we work for.

We have dedicated the book to John Wilson Lewis, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Stanford University. John was the catalyst for Carl’s career in China and, indirectly, Fraser’s as well. Without his support and encouragement, it is fair to say that this book and anything else we have done over the years in China might never have happened. We both continue to be very much in debt to our wives and families who have continued to at least tolerate our curious interest in Chinese financial matters. We promise to drop the topic for a while now, even though we are well aware that there remains much that needs to be looked at in the financial space, including trust companies and asset-transfer exchanges. May be next time.

Beijing and Singapore

October 2010

List of Abbreviations

| ABC | Agricultural Bank of China |

| AMC | asset-management company |

| BOC | Bank of China |

| CBRC | China Banking Regulatory Commission |

| CDB | China Development Bank |

| CGB | Chinese government bond |

| CIC | China Investment Corporation |

| CP | commercial paper |

| CSRC | China Securities Regulatory Commission |

| ICBC | Industrial and Commercial Bank of China |

| MOF | Ministry of Finance |

| MOR | Ministry of Railways |

| MTN | medium-term notes |

| NAV | net asset value |

| NDRC | National Development and Reform Commission |

| NPC | National People’s Congress |

| NPL | non-performing loan |

| PBOC | People’s Bank of China |

| SAFE | State Administration for Foreign Exchange |

| SASAC | State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission |

CHAPTER 1

Looking Back at the Policy of Reform and Opening

“One short nap took me all the way back to before 1949.”

Unknown cadre, Communist Party of China

Summer 2008

It was the summer of 2008 and the great cities of eastern China sparkled in the sun. Visitors from the West had seen nothing like it outside of science fiction movies. In Beijing, the mad rush to put the finishing touches on the Olympic preparations was coming to an end—some 40 million pots of flowers had been laid out along the boulevards overnight. The city was filled with new subway and light-rail lines, an incomparable new airport terminal, the mind-boggling Bird’s Nest stadium, glittering office buildings and the CCTV Tower! Superhighways reached out in every direction, and there was even orderly traffic. Bristling in Beijing’s shadow, Shanghai appeared to have recovered the level of opulence it had reached in the 1930s and boasted a cafe society unsurpassed anywhere in Asia. Further south, Guangzhou, in the footsteps of Shanghai Pudong, was building a brand new city marked by two 100-storey office, hotel and television towers, a new library, an opera house and, of course, block after block of glass-clad buildings. Everyone, it seemed, was driving a Mercedes Benz or a BMW; the country was awash in cash.

In the summer of 2008, China was in the midst of the hottest growth spurt in its entire history. The people stirred with righteous nationalism as it seemed obvious to all that the twenty-first century did, in fact, belong to the Chinese: just look at the financial mess internationally! Did anyone even remember the Cultural Revolution, Tiananmen, or the Great Leap Forward? In a brief 30 years, China had rejected communism, created its own brand of capitalism and, as all agreed, seemed poised to surpass its great model, the United States of America, the Beautiful Country. Looking around at China’s coastal cities bathed in the light of neon signs advertising multinational brands, their streets clogged with Buicks and Benzes, the wonder expressed by the confused Party cadre’s comment—“One short nap took me all the way back to before 1949”—can be well understood. In many ways, the past 30 years in China have seen a big rewind of the historical tape-recording to the early twentieth century.

The West, its commentariat and investment-bank analysts all saw this as a miracle because they had never expected it. After all, 30 years ago China was barely able to pull itself off the floor where it had been knocked flat by the Cultural Revolution. Beijing in 1978 was a fully depreciated version of the city in 1949 minus the great city walls, which had all been torn down and turned into workers’ shanties and bomb shelters. When the old

Quotations from Chairman Mao

billboards were painted over in 1979, one new one depicted a Chang An Avenue streaming with automobiles: cyclists glanced in passing and pedaled slowly on. Shanghai, the former Pearl of the Orient, was frozen in time and completely dilapidated, with no air-conditioning anywhere and people sleeping on the streets in the torrid summer heat. Shenzhen was a rice paddy and Guangzhou a moldering ruin. There was no beer, much less ice-cold beer, available anywhere; only thick glass bottles of warm orange pop stacked in wooden crates.

THIRTY YEARS OF OPENING UP: 1978–2008

As a counterpoint to the Olympics and 2008, Deng Xiaoping, during his first, brief, political resurrection in 1974, led a large Chinese delegation to a special session of the United Nations. This was a huge step for China in lifting the self-imposed isolation that prevailed during the Cultural Revolution. Just before departing for New York, the entire central government, so the story goes, made a frantic search through all the banks in Beijing for funds to pay for the trip. The cupboard was bare: they could scrape together only US$38,000.

1

This was to be the first time a supreme leader of China, virtually the Last Emperor, had visited America; if he couldn’t afford first-class international travel, just where was the money to support China’s economic development to come from?

How did it all happen, because it most certainly has happened? How were these brilliant achievements of only one generation paid for? And the corollary to this: what was the price paid? Understanding how China and its Communist Party has built its own version of capitalism is fundamental to understanding the role China will play in the global economy in the next few years. The overall economics of China’s current predicament is well understood by international economists, but the institutional arrangements underlying its politics and economics and their implications are far less understood. This book is about how institutions in China’s financial sector—its banks, local-government “financing platforms,” securities companies and corporations—affect the country’s economic choices and development path. Of course, behind these entities lies the Communist Party of China and the book necessarily talks about its role as well.

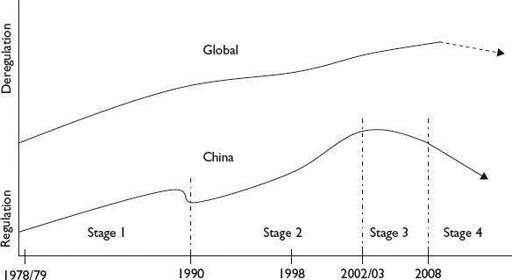

Prior to the Lehman shock of September 2008, the trajectory China’s financial development had been tracing generally followed a well-established path taken by more advanced economies elsewhere in the world. This approach was not easily adopted by a political elite that had been devastated by its own leaders for nearly 20 years and then suffered a further shock in 1989. The general story, however, has become the Great China Development Myth. It begins with the death of Mao in 1976 and the second restoration of Deng Xiaoping two years later. These events freed China to take part in the great financial liberalization that swept the world over the past quarter-century (see

Figure 1.1

). Looking back, there is no doubt that by the end of the 1980s, China saw the financial model embodied in the American Superhighway to Capital as its road to riches. It had seemed to work well for the Asian Tiger economies; why not for China as well? And so it has proven to be.

FIGURE 1.1

Thirty years of reform—trends in regulation

Source: Based on comments made by Peter Nolan, Copenhagen Business School, December 4, 2008

In the 1990s, China’s domestic reforms followed a path of deregulation blazed by the United States. In Shenzhen, in 1992, Deng Xiaoping resolutely expressed the view that capitalism wasn’t just for capitalists. His confidence caused the pace of reform to immediately quicken. China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 perhaps represented the crowning achievement in the unprecedented 13-year run of the Jiang Zemin/Zhu Rongji partnership. When had China’s economy ever before been run by its internationalist elite from the great City of Shanghai? Then, in 2003, the new Fourth Generation leaders were ushered in and things began to change. There was a feeling that too few people had gotten too rich too fast. While this may be true, the policy adjustments made have begun to endanger the earlier achievements and have had a significant impact on the government itself. The new leadership’s political predisposition, combined with a weak grasp of finance and economics, has led to change through incremental political compromise that has pushed economic reform far from its original path. This policy drift has been hidden by a booming economy and almost-continuous bread and circuses—the Olympics, the Big Parade, the Shanghai World Expo and Guangzhou’s Asian Games.

The framework of China’s current financial system was set in the early 1990s by Jiang and Zhu. The best symbols of its direction are the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, both established in the last days of 1990. Who could ever have thought in the dark days of 1989 that China would roll out the entire panoply of capitalism over the ensuing 10 years? In 1994, various laws were passed that created the basis for an independent central bank and set the biggest state banks—Bank of China (BOC), China Construction Bank (CCB), Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and Agricultural Bank of China (ABC)—on a path to become fully commercialized or, at least, more independent in their risk judgments and with strengthened balance sheets that did not put the economic and political systems at risk.

Reform was strengthened as a result of the lessons learned from the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) in late 1997. Zhu Rongji, then premier, seized the moment to push a thorough recapitalization and repositioning of banks that the world at the time rightly viewed as more than “technically” bankrupt. He and a team led by Zhou Xiaochuan, then Chairman and CEO of the China Construction Bank, adopted a well-used international technique to thoroughly restructure their balance sheets. Similar to the Resolution Trust Corporation of the US savings-and-loan experience, Zhou advocated the creation of four “bad” banks, one for each of the Big 4 state banks. In 2000 and again in 2003, the government stripped out a total of over US$400 billion in bad loans from bank balance sheets and transferred them to the bad banks. It then recapitalized each bank, and attracted premier global financial institutions as strategic partners. On this solid base, the banks then raised over US$40 billion in new capital by listing their shares in Hong Kong and Shanghai in 2005 and 2006. The process had taken years of determined effort. Without doubt, the triumphant listings of BOC, CCB, and ICBC marked the peak of financial reform, and it seemed for a brief moment that China’s banks were on their way to becoming true banking powerhouses that, over time, would compete with the HSBCs and Citibanks of the world.