Red Capitalism (24 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

In its 2009 budget report to the National People’s Congress (NPC), the MOF confirmed that, overall, local governments ran major fiscal deficits. The report stated that total local revenues amounted to RMB5.9 trillion (US$865 billion), of which RMB2.89 trillion (US$423 billion) derived from tax-transfer payments from the central government. Set against this, local-government expenditures were RMB6.13 trillion (US$900 billion). The life of a provincial governor or city mayor is dominated by a scramble to raise capital in support of local development and new jobs. Previously, SOE reform—selling off poorly performing SOEs outright or listing the shares of good ones—and attracting large amounts of foreign investment had shown the way forward for the most commercially sophisticated provinces. But there are few provinces that share the commercial attractions of China’s coastal areas. There are only so many SOEs that can be publicly listed, even on supportive Chinese exchanges. After the Asian Financial Crisis, the poorly performing SOEs had been privatized or closed entirely to preserve local resources. As a result, to increase their budgets and service their debt, local governments rely on cash flow from projects and land auctions, which reportedly contribute over one-third of local extra-budgetary revenue.

The global financial crisis of 2009 posed the greatest challenge yet to localities: Beijing’s RMB4 trillion (US$486 billion) stimulus package required local governments to identify projects and come up with financing for two-thirds of project spending. For some time before the crisis, local governments had been leveraging their utilities, roads, construction brigades and asset-management bureaus by incorporating them into limited-liability companies. Under this legal guise, they could borrow money from banks and, taking advantage of bond-market reform, issue debt. According to the CBRC, by June 2009, there were 8,221 fund-raising platforms operating at provincial, regional, county and municipal government levels, of which the majority (4,907) were owned by county governments. Many of these entities had been established simply to take advantage of the government’s free-for-all lending boom. After all, if they could come up with the capital to meet Beijing’s demands, why not raise more to finance their own economic incentive programs? It is common wisdom in China that once the window of opportunity is open, it is open for only the briefest of moments and the wise person will grab all that is possible of whatever opportunity is on offer. It is also common wisdom that when the Party takes the responsibility, the regulators will sit silently on the sidelines. Thus, in 2009, conditions were perfect for local governments to do all in their power to raise funds, with little possibility of their being blamed for financial excess.

“Financing platforms”

In those easy days of 2009, local governments and their “financing platforms” (

rongzi pingtai ) had almost-unprecedented access to credit. After a long discussion in 2008, Beijing decided that local governments would be officially permitted to run fiscal deficits. The symbol of this new thinking was the RMB200 billion (US$30 billion) in bonds issued in early 2009 by the MOF as agent for the localities. Even more important, however, locally incorporated investment companies and utilities were allowed to issue NDRC-approved enterprise bonds (

) had almost-unprecedented access to credit. After a long discussion in 2008, Beijing decided that local governments would be officially permitted to run fiscal deficits. The symbol of this new thinking was the RMB200 billion (US$30 billion) in bonds issued in early 2009 by the MOF as agent for the localities. Even more important, however, locally incorporated investment companies and utilities were allowed to issue NDRC-approved enterprise bonds (

qiyezhai ) and to these were added the new short-term PBOC securities, CP and MTNs. With the window wide open, local Party secretaries rapidly expanded their fund-raising platforms beyond simple “Municipal (or County) Investment Companies” to the incorporation of various entities such as water, highway, and energy utilities. China’s muni bond market was born.

) and to these were added the new short-term PBOC securities, CP and MTNs. With the window wide open, local Party secretaries rapidly expanded their fund-raising platforms beyond simple “Municipal (or County) Investment Companies” to the incorporation of various entities such as water, highway, and energy utilities. China’s muni bond market was born.

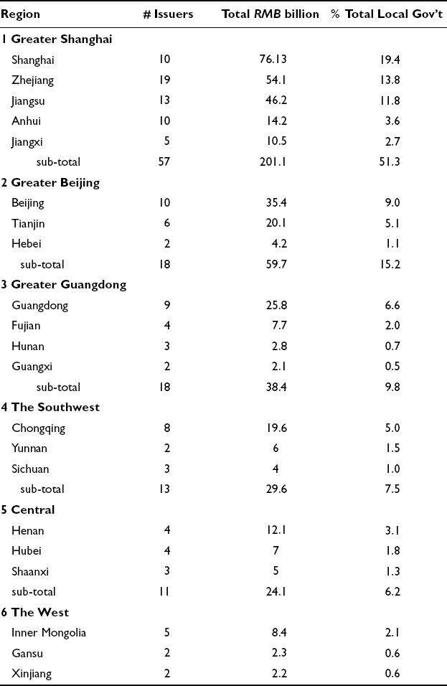

Among the many new issuers in the inter-bank market were some 140 local-government incorporated entities (see

Table 5.1

). With such names as Shanghai Municipal Construction Investment and Development Co. Ltd., Wuhan Waterworks Group Co. Ltd. and Nanjing Public Utility Holdings Co. Ltd., these entities are similar to municipal-bond issuers in the US, but with one difference. In addition to issuing long-term bonds to match the maturity of long-term investment projects, these entities also eagerly issued short-term commercial paper and MTNs. In fact, it seems they have issued every sort of debt security for which they could obtain approval.

TABLE 5.1

Local “financing platform” debt issuance, June 30, 2009

Source: Wind Information; bonds include CP, MTNs and enterprise bonds; issuers do not include local manufacturing SOEs

In 2009, the amount of capital raised in the bond markets by these provincial, municipal and county entities totaled nearly RMB650 billion (US$95 billion), accounting for over 50 percent of enterprise bonds issued and 48 percent of total CP and MTN issues. The overall explosion in CP and MTN issuance in 2009 is explained by the lack of complex approval procedures and of the requirement of a bank guarantee; issues had only to be registered with NAFMII. Making it even more attractive, MTN underwriting fees and interest expenses were lower than for the NDRC’s bonds or even bank loans. Truly, 2009 was a bonanza for some local governments. Looked at carefully, the geographical distribution of these local issuers is quite limited; fully 66 percent of local government issuers and 76 percent of all money raised came from China’s richest locations: Greater Shanghai, Beijing and Guangdong. What can explain why Zhejiang, China’s richest provincial economy, has 19 local-government issuers down to even the county level, while Henan, China’s most populous province, only four? In discussion with market participants, it seems the answer is simply that money begets money.

So the other 8,000 less-fortunate localities depended, as has been the case historically, on their partnerships with local bank branches for debt financing. How do they borrow if their resources are so constrained?

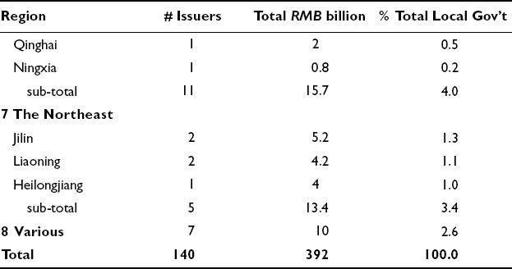

Figure 5.3

shows that one of the ways local governments capitalize their financing platforms is by contributing land and tax subsidies. The land, in turn, may be used as collateral for a bond issue or a bank loan.

FIGURE 5.3

Local-government funding alternatives

Source: Based on FinanceAsia, June 2009: 32

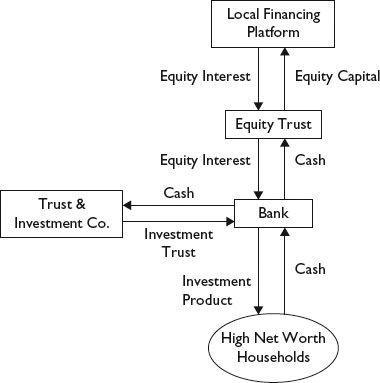

The more valuable the land, the stronger is the platform’s capacity for borrowing. The mortgaged land might be used as part of a large development for houses, office space or shopping centers. The stronger a local economy, the greater the potential profit of such a development and the greater the interest other investors may have in participating in the equity of the platform through wealth-management products developed by trust companies and sold to the banks’ high-net-worth customers (see

Figure 5.4

).

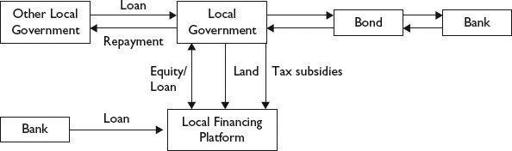

FIGURE 5.4

Trust-based financing for local financing platforms

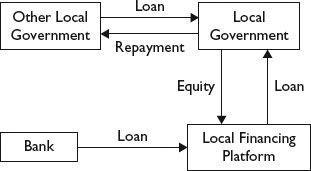

In China’s many poorer localities, these sorts of opportunities do not exist. They simply cannot meet the minimum standards of the bond markets, so they borrow from banks, as they have always done. To do so, they cut corners. For example,

Figure 5.5

illustrates how a local government may borrow from another local government and use the money to inject as capital in its financing platform. Once the capital is registered and the company is established, the local government takes back the money and repays the other local government. The financing platform exists, has nominal registered capital and business licenses and is fully able to borrow money from other banks.

FIGURE 5.5

The temporary debt-based equity capitalization of a local financing platform