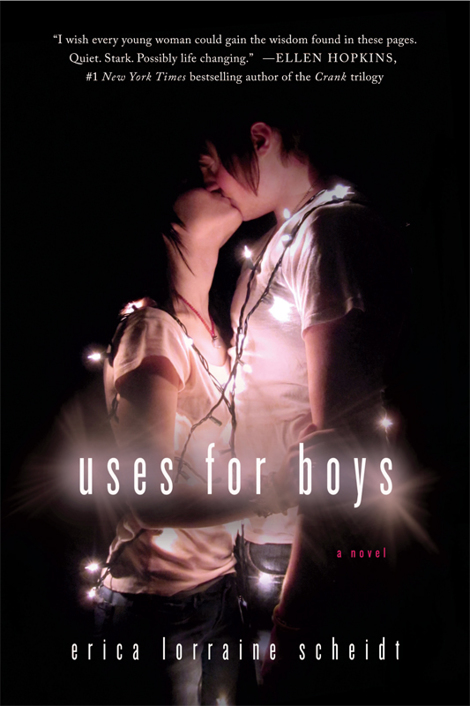

Uses for Boys

Authors: Erica Lorraine Scheidt

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Dating & Sex, #Girls & Women, #Social Issues

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only.

You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book

you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

For my mom.

And for Jennifer and Sonja.

contents

the tell-me-again times

In the happy times, in the tell-me-again times, when I’m seven and there are no stepbrothers

and it’s before the stepfathers, my mom lets me sleep in her bed.

Her bed is a raft on the ocean. It’s a cloud, a forest, a spaceship, a cocoon we share.

I stretch out big as I can, a five-pointed star, and she bundles me back up in her

arms. When I wake I’m tangled in her hair.

“Tell me again,” I say and she tells me again how she wanted me more than anything.

“More than anything in the world,” she says, “I wanted a little girl.”

I’m her little girl. I measure my fingers against hers. I watch in the mirror as she

brushes her hair. I look for myself in her features. I stare at her feet. Her toes,

like my toes, are crooked and strangely long.

“You have my feet,” I say.

In the tell-me-again times she looks down and places her bare foot next to mine. Our

apartment is small and I can see the front door from where we stand.

“Tell me again,” I say and she tells me how it was before I came. What it was like

when she was all alone. She had no mother, she says, she had no father. All she wanted

was a little girl and that little girl is me.

“Now I have everything,” she says and the side of her foot presses against the side

of mine.

eight is too big for stories

But everything changes and I’m not everything anymore. We’re in the bathroom and she’s

getting ready. His name is Thomas, she says, and he won’t like it if she’s late. She

tugs at the skin below her eyes, smooths her eyebrow with the tip of her finger. I’m

getting old, she says.

“Tell me again,” I say.

“Eight is too big for stories,” she tells me. She sweeps past me to pick out a dress

and when she does, I know. I know this dress. It’s the dress she wore the first time,

the dress she wore the last time she left me alone. It’s yellow and when I touch the

fabric, my fingers leave marks.

“Stop that,” my mom says and steps out of reach. Then she sprays perfume between her

breasts and I turn away. I know what comes next. She’ll go out and I’ll get a babysitter.

She’ll wear perfume and put on nylons. She’ll wear high-heeled shoes. The babysitter

will sit at our kitchen table and play solitaire.

“Why do you have to go?” I say.

“I’m tired of being alone,” she says and I stare at the wall of her room. The bathroom

fan shuts off in the next room. Alone is how our story starts. But then I came along

and changed all that.

“You’re not alone,” I say. My back is to her and on the wall of her bedroom are the

photographs I know by heart. The pictures that go with our story. She always starts

with the littlest one. The one of her mother.

“The last one,” my mom says, meaning it’s the last picture taken before her mother

died. She died before I was born. “She was so lonely,” my mom says. Our story starts

on the day that her father left her mother. It starts with my mom taking care of her

mother when she was just a kid like me.

I can take care of you, I think. But already she has her coat on. She’s opening the

front door because Thomas is waiting downstairs.

I look at another photo, the one of me at the beach sorting seashells and seaweed

and tiny bits of glass. In it, I’m concentrating and wearing my mom’s sweater with

the sleeves rolled up.

“Bye,” she calls and I look up, but the door is already closed.

he’s our family now

She goes out that night. She goes out the next night. I sleep alone in her bed and

when she comes home, she packs a suitcase. She’s going away for the weekend, she says.

She’s going away for the week. In between she comes home. She repacks. She washes

her nylons and hangs them in the shower. She washes her face in the sink. I watch

her in the mirror as she gets ready to go out again. She looks at her face from different

angles. She pinches and pulls at her skin.

Then I meet this man. This Thomas. She brings him home like he’s some kind of gift.

And I’m told to be nice. I’m told to stand still. I’m made to wash my face.

I stand in front of him with my arms straight down at my sides. He’s in the kitchen,

crossing in front of the light like an eclipse. Our kitchen table looks strangely

small. Our ceilings too low. I’m watching the front door and willing him to walk back

out of it. Instead he bends down until his face is even with mine.

“She looks just like you,” he says.

“You don’t look like anyone special at all,” I tell him. And I curse him. And I start

a club to hate him. And I make a magic spell to get rid of him. And when she marries

him, when we pack up our apartment and move into his house, when I change schools

and have to eat the food he likes to eat, I don’t talk to him.

“Anna,” my mom says.

“What?” I say.

“Be nice,” she says. “He’s our family now.”

our story

The pictures stay packed away. I unpack my stuffed animals and line them up against

the wall of my new room. I put the smaller ones in front so they can see. I tell them

our story. I had no mother, I tell them. I had no father.

“Tell me again,” they say.

after the divorce

I sleep alone in my bed. I eat the food he likes to eat. I learn to be quiet and when

he leaves, when he packs a suitcase and slams the door, I’m glad.

He moves out and we stay in his house, my mom and me.

“Now we have a house,” she says and she says it more than once. She wanted a house,

I think. And then I think, now we have a house. Now, I think, we’ll be happy.

“A house is like a raft on the ocean,” I tell her. And I tell her not to cry.

After the divorce, I think things will go back to how they used to be. A return to

the tell-me-again times. After the divorce, I think, we’ll unpack the photos and hang

them on the wall. After the divorce, I tell her how good she looks. And she really

does look lovely in a sad, made-up kind of way. She wears a lot of burnt orange and

dark red, dark green. She lightens her hair and talks about getting a face-lift.

But her eyes go dreamy when I speak and she never really listens.

I’m nine years old. Look, I want to say, you are beautiful. But she hates being at

home with me. Having a child is another kind of defeat.

* * *

When she does get a face-lift, it’s Armageddon—angry cuts and shiny black stitches,

a runny egg yolk of yellow-blue bruises. Her mouth and eyes are swollen. I can’t even

look at her. I won’t speak to her.

In the bathroom, I run the water in the sink and look at my face. I cross and uncross

my eyes. I frown. I smile. I close my eyes and open them really fast to catch myself.

I’m her little girl. Arms spread. I’m her five-pointed star.

All she wanted was a little girl and I’m that little girl.

“I can take care of you,” I say. I say it out loud over the sound of the water and

then I say it again. My voice is hoarse from not speaking for so long. I run into

her room to tell her. I forget and leave the water on. I burst into her room.

“I can take care of you,” I say.

But she needs quiet now, she says. The room is dark and she turns her bandaged face

away from me.

“Not now,” she says. She needs to heal.

waiting

Not now. The house is uneasy. Waiting. The worst part is that I’m alone. I watch a

thin line of ants snaking through the kitchen. I put my face so close that my breath

disrupts their path. They right themselves and keep on, winding along the wall and

down the counter and back behind the refrigerator. I fill a pitcher of water and set

it quietly on my mom’s bedside table.

after the face-lift

After the face-lift there’s a new dress. There’s a George and then a Martin. Martin

prefers the blue dress, my mom says. The new dress. George likes the yellow. Then

there’s Robert.

“He’s the marrying kind,” she says.

She doesn’t bring them home to meet me, these new ones. And when she marries Robert,

she doesn’t bring him home either. He’s not a gift to me. My mom’s new husband and

her new face stretch tight against the bones of her old one.

“We’re going to be a family,” she says when she gets back from the honeymoon. She’s

standing in the bathroom with bobby pins in her mouth, arms over her head, arranging

her hair.

“Wouldn’t you like that, Anna?” she says. “A real family?” She’s curling pieces of

hair and then pinning them up. There’s a slip over her bra and her new face is pale,

waiting to be made up. She doesn’t meet my eyes in the mirror. She’s married a man

with two sons, I learn. She goes on, curling, twisting, pinning.

“And you must be Anna,” my mother’s new husband says when we meet. “This is Anna,”

he says, turning to his sons.

“Hi,” I say. They’re bigger, older than me, hunched over in identical jackets. Sullen,

acne-strewn boys who look warily at my mom and me. My mom is not a gift to them either.

The five of us move into a big house in the suburbs outside of Portland. A big new

house with a big yard and tall glass windows.

“I always wanted a house like this,” my mom says and she sighs and puts her arm over

my shoulder. “This,” she says, “is the house I always wanted.”

we’re a family now

I don’t want this house. I want to go back to the tell-me-again times when I slept

in her bed and we were everything together. When I was everything to her. Everything

she needed.

I unpack my stuffed animals and line them up against the wall of my new room. I put

the baby ones in front so they can hear. I tell them our story. “I had no mother,”

I say. “I had no father.” I was all alone and all I wanted was a little girl, I tell

them. I pick a different one each time. “You,” I tell a blue stuffed bear. “You are

my little girl.”

It’s a deep Oregon summer and the sun fights its way into the yard through the dense

pine. It’s hot and every day I wear the same blue shorts and my favorite pair of sneakers.

I cut my own bangs and my mom says they’re crooked and half in my eyes. My room is

upstairs, near her and the stepdad. The boys have their rooms downstairs.

“We’re a family,” my mom says. But we’re not a family. We’re something else.

the stepbrother

I’m on the living room floor eating cereal and watching cartoons in a patch of morning

sun. It’s Saturday, but school’s out anyway. I spill the milk and wipe it up with

the hem of my T-shirt. I go back to the kitchen for another bowl. I don’t even see

it coming. A sharp crack and the tall glass window shakes like it’s been slammed with

a rock. The television is suddenly loud.

I’m out the door, racing around the side of the house. My sneakers skid against the

bark dust. By the time I get there, the younger stepbrother is already crouched next

to the injured bird. I look up at the window and see the reflection of trees, the

faint smudge from its body where it sped headlong into the glass.

The stepbrother picks it up and cradles it in his hands. Cups it close to his chest.

The shade makes patterns on his face. There are patterns all around us. I’m holding

my breath and I can feel my heartbeat. I can see the tiny movements of the bird’s

chest. I’m hoping for something different. The stepbrother is hoping. We’re holding

our breath. The stepbrother is close enough to touch. It’s the sweaty middle of day.

I’m hoping so hard I can feel the throb of it in my ears.