Red Capitalism (15 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

What were included in such problem assets?

10

On Huida’s business license, the targeted assets were related to real-estate loans in Hainan and Guangxi and portfolios assumed as part of the GITIC and the Guangdong Enterprise bankruptcies. Interestingly, these figures are not included in

Table 3.6

, but can be estimated at around RMB100 billion.

11

Despite such explicitness, financial circles at the time believed that the PBOC’s real intention was to put Huida in charge of working out the loans, totaling RMB634 billion, the central bank had made to the four asset-management companies in 2000. With a capitalization of just RMB100 million, whether it assumed the old problem assets or any part of the PBOC’s more recent AMC loans, Huida was going to be highly leveraged.

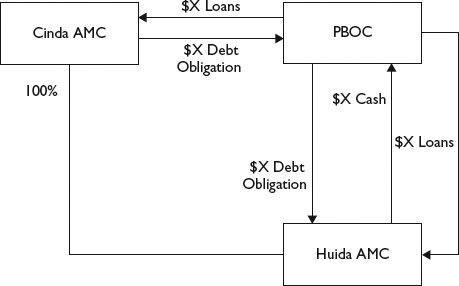

Assuming Huida did take on some or all of the PBOC’s AMC loans, such a transaction is illustrated in

Figure 3.9

. As previously described, the PBOC made loans to Cinda AMC in 2000 to enable it to purchase, on a dollar-for-dollar basis, problem-loan portfolios from China Construction Bank. These loans became assets on the balance sheet of the central bank that it then sold to Huida. Huida could only pay for such loan assets, however, if the PBOC lent it money in turn, which appears to have been the case. The net result of such a transaction was that Huida owned the loan assets associated with Cinda, while on its own books, the PBOC now held Huida loan assets.

FIGURE 3.9

The transfer of AMC loan portfolios to Huida

The only problem with this arrangement is that Huida is a 100 percent subsidiary of Cinda AMC. In other words, Cinda’s loan obligations to the PBOC (and ultimately Huida) were being held by itself. If such accounts could be consolidated, then the assets would offset the liabilities and everything would just disappear! None of this makes sense, except from a bureaucratic angle: the PBOC was able to park problem assets off its own balance sheet and Cinda—as a non-listed, and undoubtedly non-audited, entity—had no need to consolidate Huida on its own balance sheet. At best, these loans became a contingent liability: if Huida could not collect, then the PBOC’s loan to Huida would not be repaid. As noted previously, contingent liabilities (

biaowai zhaiquan ) are not considered to be real in China’s financial practice; where in the national budget report are such things mentioned? A look at Cinda AMC’s excellent website fails to provide any proof of Huida’s existence as a 100 percent subsidiary. One wonders if there is a sixth or even a seventh asset-management company lurking out there in China’s financial system.

) are not considered to be real in China’s financial practice; where in the national budget report are such things mentioned? A look at Cinda AMC’s excellent website fails to provide any proof of Huida’s existence as a 100 percent subsidiary. One wonders if there is a sixth or even a seventh asset-management company lurking out there in China’s financial system.

But this is all just window-dressing compared to the PBOC’s huge exposure to foreign currencies, shown as “Foreign Assets” on its balance sheet. Strengthening its capital base, therefore, would appear prudent. By doing so, the government could openly demonstrate its commitment to a strong banking system. Of course, the sovereign, with its vast riches, stands behind the PBOC, but it is not so simple.

China’s massive foreign-exchange reserves give a false appearance of wealth: at the time the PBOC acquires these foreign currencies, it has already created renminbi. Under what conditions can these reserves be used again

domestically

without creating even larger monetary pressures? As they are, the reserves are simply assets parked in low-yielding foreign bonds and Beijing’s ability to use them is very limited. If the MOF is content to extend the life of the AMCs, consider how much more politically complex the issue of recapitalizing the PBOC would be.

In any event, the government appears to lack the desire to take on such subjects. The pressure to pursue meaningful financial reform has diminished since the struggles of 2005. Drowned in the flood of Party-supported “loans”, China’s banks in 2009 were back to where they left off before the entire recapitalization program began in 1998: they are financial utilities directed by the Party, just as was the case when the Great Leap Forward began more than 50 years ago. Whatever problems may arise can easily be dealt away to obscure entities that few know or will remember.

CHINA’S LATEST BANKING MODEL

As Chen Yuan remarked, China should not bring “that American stuff over here . . . it should build its own banking system.” It is doing just that with the bits and pieces of its old financial system that have been assembled by the asset-management companies. Before the final clean-up of the Agricultural Bank of China and the 2009 loan surge, the fate of the AMCs was actively discussed among the Big 4 banks and the State Council. What should have happened, but apparently will not happen now, was described thus by one of their senior managers:

For losses stemming from the first package of policy NPLs, the state will bear the burden [an estimated US$112 billion]. The losses on the commercially acquired NPLs [an estimated US$64 billion] are to come from the AMCs’ own operating profit after deducting the PBOC re-lending interest. If the price the NPLs were acquired at was not right, then any losses on the PBOC’s loans will be made up by AMC capital. In the end, the most likely outcome is that the AMCs will have to wrangle with the state.

12

This AMC official knew full well that if the AMCs were to take write-offs, they would be bankrupted, forcing the MOF to step in and cover the value of their outstanding bonds and loans from the PBOC. Failing this, the banks would bear losses to their capital that they were (and are) not in any position to bear.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, however, changed this equation completely. The Chinese government acted as if a veil had been removed from its eyes as the international banking system teetered on the verge of collapse. Since at least 1994 and certainly from 1998, bank reform and regulation had been based on the American financial experience. Citibank, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs and Bank of America were seen as the epitome of financial practice and wisdom. This American model and the vigorous efforts of the bank regulator and other market-oriented reformers to channel Chinese financial development within its framework immediately lost all credibility. But there was nothing to take its place. The banks, suddenly without restrictions, not only went on their famous lending binge, but also sought to grab as many new financial licenses as possible. As one senior banker said: “No one knows what the new banking model will be, so in the meantime, it’s better to grab all the licenses we can.” The easiest place to find a handful of these licenses was the AMCs. How did they come by so many?

In addition to taking on problem-loan portfolios from the banks, the asset-management companies also assumed the debt obligations of a host of bankrupt securities, leasing, finance, and insurance companies and commodities brokers. Of the collapse of this part of China’s financial system just five years ago, the world remains ignorant. In many of these cases, the AMCs were meant to restructure debt into equity and then sell it to third parties, including foreign banks and corporations. The proceeds of such sales would have partially or, if well negotiated, fully repaid the old debt. But in the great majority of cases, these zombie companies were never sold, nor were they closed. Ultimately, their names changed and their staff employed, they emerged as AMC subsidiaries. Orient AMC, for example, proudly boasts a group of 11 members, incorporating securities, asset appraisal, financial leasing, credit rating, hotel management, asset management, private equity and real-estate development. Cinda, the largest and most aggressive AMC, has 14, including securities, insurance, trust and fund-management companies. By acquiring the parent AMCs, Chinese banks could in one swoop hold licenses that would, on the surface, catapult them into the league of universal banks.

Of course, the banks were egged on by the AMCs, which did not want to be closed down. There was also an element of vindication: the AMCs were the repositories of unwanted staff who had been spun off as part of bank restructuring. Both began a game of chicken with the government, with the NPL write-offs as the target. By mid-2009, persistent rumors emerged that ICBC and CCB had each submitted concrete plans to the State Council to invest up to US$2 billion for a 49 percent stake in their respective affiliated AMCs. The very idea is astounding: 49 percent of what? But this was no rumor: by late 2009

Caijing magazine reported that the State Council had approved CCB’s 49 percent investment in Cinda valued at RMB23.7 billion (US$3.5 billion), with the MOF continuing to hold the balance.

magazine reported that the State Council had approved CCB’s 49 percent investment in Cinda valued at RMB23.7 billion (US$3.5 billion), with the MOF continuing to hold the balance.

13

The total resulting registered capital of Cinda, including the MOF’s original RMB10 billion, was reported to be RMB33.7 billion. This is outrageous because it means not a penny of losses—operating or credit—had been taken by Cinda over its 10 years of operation. This is simply not possible, even if Cinda were the best-managed of the four companies. Or perhaps the operations of its myriad new subsidiaries had offset such losses. Who knew?

Even were it not bankrupt, one wonders at the amazing valuations characterizing the proposed Cinda transaction. Are Cinda and its unknown subsidiary, Huida, any different from those puffed up special-purpose vehicles whose deflation led to the bankruptcy of Enron, not to mention the near collapse of the American financial system in 2008? And there was more to the new arrangements. On the same day the Cinda deal was mooted, the MOF announced that Cinda’s RMB247 billion bond owed to CCB was to be extended for a further 10 years. This action undoubtedly represents the first step to extending the institutional life of the other three companies as well.

14

The year 2009 marked the end of banking reform as advanced since 1998. What will follow is beginning to look like a glossier version of the old Soviet command model of the 1980s and early 1990s. In the end, the Cinda deal could not be done in its proposed form. By mid-2010, however, a new structure for Cinda had been rolled out. Cinda was incorporated, with the MOF as the sole shareholder, and its valueless assets, including the loans it owes the PBOC, were spun off into the now increasingly ubiquitous “co-managed account” in return for more MOF IOUs. This left Cinda and its bevy of financial licenses able to begin the search for a “strategic investor,” which, of course, is expected to be CCB. From this continual recycling of debt, it seems that, despite its fantastic riches, the Party—and certainly the MOF—lacks the wisdom and the determination to complete the bank reform begun in 1998.

IMPLICATIONS

The question is often raised: does it matter how the Party manages this machinery for failed financial transactions? China, after all, has the wealth to absorb losses of this scale, if it is determined to do so. The answer to this question must be “Yes.” Every day, the press carries stories about China’s National Champions and its new sovereign-wealth fund seeking out investment opportunities in international markets. The internationalization of the renminbi has made headlines as China seeks to challenge the dominance of the dollar as the international currency for trade and, perhaps someday, the international reserve currency. But little is heard from China’s banks; why?