Plymouth (12 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

In August 1768 Captain James Cook set out from Plymouth on the

Endeavour,

en route to Tahiti to observe the transit of Venus, measurements for which would help scientists determine the distance between the Earth and the Sun. He also had secret orders, never revealed until they were discovered in the Navy Records in 1928, to find the great south land, at that time only fleetingly glimpsed by explorers. His journey would be an incredible success, with the discoveries of New Zealand and the eastern coast of Australia. His first stop at Rio de Janeiro did not go well, however, as the Portuguese Viceroy mistook them for pirates and temporarily imprisoned members of his crew.

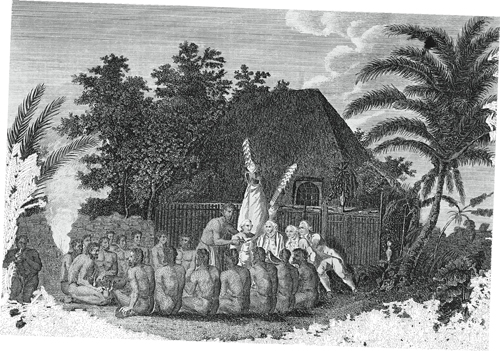

Captain Cook receiving offerings in the Sandwich Islands. (LC-USZ62-102228)

Then, at Tahiti, his crew all caught syphilis.

Well, not quite all of them, and it proved not to be syphilis (though the symptoms were very similar). As the male European sailors explored the Pacific islands and grew intimate with the friendly islanders, especially the women, a venereal disease called yaws became endemic throughout the islands. If a sailor brought a cut or scratch into contact with the skin of an infected islander, a painless ‘mother yaw’ would spring out, looking somewhat like a wart. These would then burst out into ulcerous lesions, and the disease would begin to eat into the bones, joints and soft tissues of the victims, particularly the nose. This was often eaten quite away, leaving a huge crater in the victim’s face.

Cook himself was adamant that his group of explorers should always be friendly with the natives they met on their journeys, but so not friendly that they introduced sexual diseases to the native populations. Unfortunately there was little Cook could do to prevent it, as the islanders had already caught the disease from previous explorers and traders, and Cook’s crew were just another of many to whom venereal diseases would be passed on. Soon yaws and other diseases would cause havoc through the Pacific Islands.

![]()

In 1787, the ships

Friendship

and

Charlotte

set sail from Plymouth carrying male and female convicts to join the First Fleet, which would form the first European settlement in Australia. The fleet carried a total of 1,044 people, which included 504 male convicts and 192 female convicts, as well as – all the more horrifying – 17 children of convicts. The First Fleet tried to establish a colony at Botany Bay, under the advice of Captain Cook, but found no fresh water there. The land was also poor, so they sailed further north and eventually landed in Port Jackson, now called Sydney Harbour. The resulting colony suffered great deprivations in their first years, desperate for supply ships which turned up much later than expected. The land around Sydney was not much more fertile than Botany Bay, and food was scarce for many years. The convicts working in the heat in heavy chains were brutally abused by their marine overseers. One of the worst early effects of the settlement was the accidental introduction of smallpox, which devastated the Aboriginal population.

![]()

In 1789 the friendly natives of Tahiti were the ruin of Captain Bligh, whose crew mutinied on the

Bounty

, preferring to remain in their Tahitian idyll rather than return to their miserable lives in England. Though Bligh’s brutal discipline was blamed for the mutiny, his methods were in fact no worse than any other captain’s – floggings and other punishments were regular occurrences aboard the naval ships. Order had to be maintained. Cook was renowned as a more liberal task-master than most, but even he had to punish his men for insubordination, though their behaviour was much improved by his determination to see them well-fed and disease-free.

Captain Cook, despite his more open-minded attitudes towards native peoples and his liberal treatment of the crew, had his flaws – he was prone to tetchiness and temper – and it was these flaws that led to his own death. In 1776 Cook set out from Plymouth on his third voyage, in his ships the

Discovery

and the

Resolution

, intending to explore the Baring Strait and investigate the possibility of a passage from the Pacific into the Atlantic around the northern coasts of America. En route, he discovered the Hawaiian Islands, and explored Easter Island and the northern coasts of America. In the islands of the Pacific, Cook was frequently hailed as a god, and, although usually coping with the rituals and the adoration with humility, there was more than a little hint in his final days that the admiration had finally gone to his head.

Landing in Kealakekua Bay in Hawaii, he and his crew were again hailed as gods – but as the gods consumed all the food the deprived natives were more than happy to see the ships sail away at last. Cook had outstayed his welcome. However, the

Resolution

had been poorly fitted and, within a week, Cook was forced to return to Kealakekua for repairs. The natives were not impressed to see them back so soon. Expecting something in return for their hospitality, a group of them took a cutter from the

Discovery

. They wrongly assumed that this would be understood by Cook and his crew as their fair due. It was a cultural misunderstanding that was to have catastrophic effects: tetchy in his old age, Cook rushed to the shore, determined to take the island’s King hostage until the cutter was returned.

The King and his two sons were actually quite happy to come aboard Cook’s fine ship, but the Queen, in tears, begged for the return of her family – and the watchful Hawaiians decided that enough was enough. Cook found himself confronted by an angry mob. Muskets were fired in the panic and a Hawaiian chief was accidentally killed. The native men, armed with spears and stones, threatened Cook. Cook himself fired two shots to dissuade any further attack. Stones rained down upon Cook’s men, who retaliated with more shot. Then, as Cook turned to his men to demand they cease firing, one of the warring natives stabbed him in the back.

As his men retreated, Cook’s body was left on the shore at the mercy of the locals, who tore it apart. While the crew watched from their ship, unsure how to proceed, Cook’s mutilated body was afforded a fine native funeral: it was dismembered, cooked and the pieces distributed amongst the natives. Captain Clerke, who assumed command, then had the grisly task of trying to collect the remnants of Cook’s body, so that a ‘proper’ sea-burial could be performed.

![]()

In 1803, Ann Croot was sentenced to seven years’ transportation to Australia for stealing a shawl, a mason’s hammer and a trowel, but the inspector of convicts refused to put her on board the ship, alleging that age and weak health meant she would die en route. On 9 January 1804, she was pardoned.

![]()

Realising that the death was not an act of war but desperation, Clerke very wisely ordered that there be no retaliation against the natives, who, once calmed, were very sorry for the death of a man they had admired. One of the Hawaiian priests came on board to offer Clerke a tribute – a disgusting bundle of burnt flesh wrapped in cloth. Although they ritually dismembered the body, the story that the Hawaiians were cannibals is proved untrue by Clerke’s diaries. The natives were asked if they had eaten any of Cook’s body – a very difficult discussion requiring delicate translation. Clerke recorded that the islanders were horrified by the thought; when they realised what the captain was asking, they denied it hotly. Pieces of Cook’s body were merely to be distributed as powerful tokens, not for human consumption.

Unfortunately, Captain Clerke then fell ill. During his incapacitation, a number of natives were slaughtered by the angry crew, their houses burnt to the ground. Suing for peace, the Hawaiian chiefs finally returned to Clerke a series of gruesome peace offerings – the head, hair and limbs of Captain Cook, for burial at sea.

Captain Cook may have died in the warmth of Hawaii, but his previous voyage had been a far chillier affair. Cook was dismayed by the prospect of the frozen waste that was Antarctica. On his second voyage, leaving Plymouth in 1772, he described in his diaries ‘the inexpressible horrid aspect of the Country; a Country doomed by nature never once to feel the warmth of the Sun’s rays, but to lie forever buried under everlasting snow and ice.’ He felt that ‘whoever has resolution and perseverance to [proceed] farther than I have done, I shall not envy him the honour of the discovery but I will be bold to say that the world will not be benefited by it.’