Plymouth (14 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

Hanging from the yardarm.

Meanwhile, there were rumours that enemies of the government had entered the Navy with the sole purpose of causing the disruption. One of these was an attorney called Lee, a rebellious man and a member of the United Irishmen, a Republican revolutionary group influenced by the American and French Revolutions. Lee joined the Navy, but it was soon discovered that he had enlisted with the object of spreading sedition. A drummer boy, sleeping under a hedge near Stonehouse, overheard conversations between Lee and his marine colleagues in which they pledged to start a treasonable uprising and free all the French prisoners. They vowed not to rest until ‘they had overturned the government’. The boy alerted the officials at Stonehouse Barracks, and Lee and his comrades, Coffy and Branning, were tried and sentenced to be executed.

An old soldier called John McGennip, who, it was claimed, had encouraged Lee’s plans, was mercilessly flogged on Plymouth Hoe in front of the vast crowd, before being prepared for departure to Botany Bay. Then Lee, Coffy and Branning emerged from the Citadel. A marine band led the condemned party onto the Hoe, playing Handel’s

Dead March

and accompanied by the three coffins held aloft. The three men were lined up and forced to kneel on their own coffins, and then the firing party approached.

Coffy and Branning fell at the first volley, but Lee remained untouched. One of the firing party then walked up to Lee with a loaded revolver. Placing the muzzle at Lee’s ear, he blew off the top of his head.

Hundreds of troops were then paraded around the corpses in silence, as a warning to all who attempted sedition, and thousands then followed the procession of filled coffins to the Citadel. A contemporary account describes the procession as ‘one of the most awful scenes the human eye has ever witnessed’.

1799

THE BREAD REBELLION

W

HILE HORATIO NELSON

was famously fighting the French Revolutionary Wars, Britain was in turmoil. In 1799 the crops of wheat and barley, and then potatoes in Cornwall, failed, and with the wars in Europe, imported cereals became very expensive. The price of bread inflated beyond the ability of the majority of people to pay for it. Riots broke out across the country. Bakers’ shops became battlegrounds as people desperately haggled over prices. In September 1800 the crops failed again, prices rocketed – and all hell broke loose.

By March 1801 the people of Plymouth were starving. In the three towns of Plymouth, Stonehouse and Dock (later called Devonport), there was a population of 47,000, with 3,000 people working at the Royal Dockyard; a high concentration of urban workers requiring enormous amounts – 220 bushels a week – of barley and wheat. With the failure of the crops, grain became expensive and the Plymouth Corporation valiantly tried to provide subsidies for the poor, but only managed this through the winter. By March, grain became like gold dust. Wars in Europe meant imported grain was no cheaper.

The Government tried bread substitutes – the failure of the potato crop not really helping matters – but the population were unimpressed at the prospect of imported herring for breakfast. By March 1801, there was less than 48 hours’ worth of staple foodstuff in stock in Plymouth. The area simply ran out of food.

Many throughout the country, including some Plymouth magistrates, thought that the scarcity was an attempt by hoarding farmers to inflate prices. There was possibly some truth to this rumour, as the farmers could get very high prices indeed if they transported their grain to London. On 23 March, a protest started in Exeter: a mob of 300 attacked the local farmers, threatening a lynching if they didn’t lower their prices.

On 30 March, it was Plymouth’s turn. A mob gathered in Plymouth, and prices were reduced in the market the following day; Plymouth’s farmers went in fear of their lives. However, the bakers refused to comply, and the mob started smashing windows. One Plymouth baker was a member of the Volunteer Cavalry and successfully faced down the crowd with a drawn sword, but the protesters became so unruly that troops were called in – 1,400 militia in Plymouth and seventy cavalry from Dock (Devonport). The cavalry charged.

Two women and a dockyard worker were arrested, but the unrest continued. The highly organised dockyard workers went on strike in protest at their colleague’s arrest, coming out of the yard ‘in a body, whooping and huzzaing’. They were met with a troop of the Queen’s bayonets, the pickets of the Wilts and East Devon and four loaded cannon. The Dockyard Committee demanded the release of the prisoner – and they got it, the magistrates siding with the people and releasing the dockyard protestor. The Committee also got the butchers and bakers to agree to set lower prices.

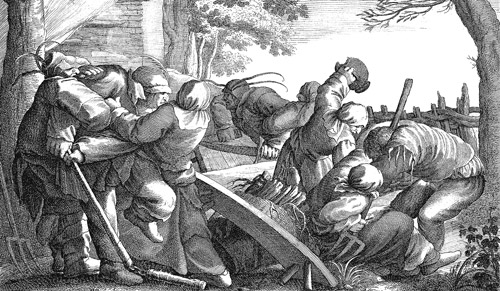

Food riots broke out across the country in 1799. (With the kind permission of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto)

However, the bakers reneged on the deal and sent corn east to get higher prices. London received word of the dangerous precedents being set in Plymouth, and sent Lord Lieutenants Poulett and Fortescue to enforce the ‘free market’; no price fixing by the dockyard workers would be tolerated. Colonel Bastard – yes, you read that correctly – of the South Devon Militia confiscated the side arms of any volunteer soldiers, and brought in professional troops to patrol the streets.

But the free market did nothing to prevent starvation, and soon the people of Plymouth, Stonehouse and Devonport were out again in protest. Rumours that a Devonport baker was hoarding sixty sacks of flour led to the mob attacking and robbing his shop. This attack lowered prices in the market again, but the troops, as before, made an arrest that led to a riot: Charles Jacob was taken up for smashing a window, whereupon the enraged crowd broke into the courthouse with battering rams and forced his release. Jacob was hidden away in the dockyard while the crowd smashed the magistrate’s windows. (Ironically, the magistrate was St Aubyns, a major brewer dependent himself on a good supply of grain.)

Market Day in Taunton. A hundred years before this peaceful scene was captured, residents watched in horror as two men were executed here for their part in the bread riots. (LC-DIG-ppmsc-08886)

During Jacob’s rescue from the courthouse, two dockyard workers were arrested and the protesting mob on the street just got bigger. To be fair to the mob, they were protestors, not criminals – one fellow who stole a bag of potatoes during the turmoil was attacked, captured and handed over by women in the mob.

Troops locked the gates at the dockyard in an effort to starve out the protestors. However, they couldn’t blockade the port, and some dock men sailed up the Yealm on 23 April. There they threatened the farmers again, forcing them to sell corn at reduced prices. A gunboat eventually captured and arrested the party, but by then a criminal gang had got in on the act and attacked Honey’s farm near Plympton, causing irreparable damage. Two of the gang were subsequently tried in Exeter and executed.

The authorities knew that something had to be done. The Navy Board reached Plymouth in May 1801 and sacked sixty-eight dockworkers: seventeen blacksmiths, twenty-two shipwrights, eleven labourers, six carpenters, three caulkers and three sailmakers, including all the union representatives who were on the Dockyard Committee which initiated the strikes. The butchers of Plymouth responded by raising the price of meat, declaring, ‘that they shall do what they like now the Dockyard men are silenced’.

To quell further outbreaks of unrest in the South West, two men in Taunton, Samuel Tout and Robert Westcott, were sentenced to death for their involvement in the riots and executed in the middle of the marketplace. The subdued crowd watched in horrified silence. There were no more riots.

1815

THE NAPOLEON EXHIBITION

I

N 1815 NAPOLEON

arrived in Plymouth. The Battle of Waterloo finally ended the war with France and the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, a military genius and dictator, was taken prisoner. In July 1815 the HMS

Bellerophon

(known to most as the ‘Billy Ruffian’) sailed into Plymouth Sound with Napoleon on board, on his way to exile on the Atlantic island of St Helena. To the British he was an unimaginable tyrant, and yet here he was in the flesh, seemingly benign. Thousands of small craft flocked to the Sound to catch a glimpse of the Emperor as he strolled on the deck, amused by all the attention and willingly posing for excited onlookers.

This engraving is based on the famous Eastlake painting: it shows Napoleon in his uniform, as approved by the man himself. (LC-DIG-pga-02908)

![]()

In the old Freedom Fields Hospital, a third-year student nurse once spotted a short man in a blue uniform running down a staircase. Security reassured her it was just the resident ghost of a Napoleonic prisoner of war.

![]()

![]()

The souls of over 100 French prisoners hanged in the Naval Dockyard still allegedly remain trapped in the oppressive atmosphere of the Hangman’s Cell, which contains the last remaining working gallows in Britain. In the nearby Ropemakers’ House, ghost hunters have sighted a phantom Victorian girl.

![]()