Plymouth (4 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

After some false starts due to bad weather, King Edward I assembled a great fleet of 325 ships at Plymouth in January 1296, under the leadership of his brother Edmund. But Edmund sickened and was dead by June, leaving the Earl of Lincoln to lead the attack on French forces mobilising in Gascony. As the fleet sailed, the King and his entourage stayed at Plympton Priory. It was a costly war, ended only by a truce negotiated by the Pope himself, which was then strengthened by a marriage between King Edward’s son and King Philippe’s fourth child, Isabella.

Battles over the treaty raged on and on, claims and counter-claims going on for years, until the worst possible outcome for the French throne: Philippe IV’s eldest sons died, leaving the throne of France in dispute, and Isabella, wife of the now King Edward II, with a rightful claim. (Although the French later passed a law that women could not accede to the French throne, Isabella’s son retained a claim, sowing the seeds for the Hundred Years’ War between England and France.)

In 1324 Edward II and a younger son of Philippe IV fought a brutal short war in Gascony, and the English forces were decimated. Some say this defeat alone led to King Edward II being deposed by his own wife, Isabella – behind every failed man is a bitter woman! Their son was then crowned King Edward III. In 1328 the last son of Philippe IV died and the French throne passed to a cousin, proclaimed King Philippe VI (with number V already dead!). The English King Edward III retained the stronger claim on the French throne and an overwhelming desire for payback against the French.

Edward I, who stayed at Plympton Priory whilst his troops were attacking France.

However, Gascony was worth a fortune to the English: its wine and salt were exceedingly profitable. King Edward III therefore did a deal that he would forfeit his claim to the French throne in return for Gascony alone. Philippe VI reneged on the deal and invaded Gascony anyway, and war was declared (again) with open hostilities.

Suddenly French ships were raiding settlements along the Devon and Somerset coasts, and in 1337 all available English forces were put on alert. A series of beacons, fuelled by pitch and manned constantly by five-man crews, were established on all high grounds and headlands to announce the sight of any invading French ships. All coastal cities were frantically fortified, their defences reviewed and strengthened, and all available men conscripted into a militia called the ‘Garde de la Mer’.

In 1339 Plymouth was attacked by eighteen French ships and the population fled inland in fear of the French ‘pirates’. The invasion was successfully repulsed by forces led by the Earl of Devon, Hugh Courtenay. His forces for the entire Devon coastline consisted of just 175 armed men and 140 archers, but they managed to stave off the French attack. The historian Stowe described the fighting (with spelling amended for clarity):

At length they entered Plymouth Haven, where they burnt certain great ships and a great part of the town... There they were met by Hugh Courtenay, Earl of Devon, a knight of four-score years. A hand to hand fight followed; many of the pirates were killed, and the residue fled back to their galleys. Not being able to come upon them by wading, many were drowned in the sea to the number of 500; of the townsmen, only 89 were killed. A second attack was repulsed, and the enemy retired to Southampton.

On 1 August 1340 the French attacked Plymouth again. They first burnt Teignmouth, then they assailed Plymouth, but, finding it well-defended, they did little damage – apart from burning some farms and taking a knight prisoner.

In the meantime, King Edward III received news that the French were amassing a fleet of 190 ships to invade England. He launched a pre-emptive strike, which destroyed almost all of the French ships in the Battle of Sluys. The English archers unleashed a torrent of arrows before leaping aboard the French ships and forcing thousands of French soldiers into the sea, where they drowned.

The news of the defeat was allegedly broken to the French King by his jester, who informed the King that the English were cowards. ‘How so?’ enquired the King. ‘Because they have not the courage to leap into the sea, like the French and Normans at Sluys,’ he replied. Tens of thousands of French troops were killed, and their bloated corpses would have floated to the surface by the harbour for weeks afterwards. Though Edward III himself was wounded in this battle (hit in the thigh with either an arrow or a crossbow bolt, it is thought), it put an end to the threat of French invasion for some time.

Edward then launched his own counter-invasion in 1346, with Plymouth sending twenty-six ships, manned by 603 men, to join an invading fleet. After capturing Caen, the English forces trounced the French at the Battle of Crecy, largely due to some fortunes in the weather, but mostly due to the power and skill of the English archers. Their 5ft-long yew bows could fire a 3ft arrow with a steel tip able to penetrate a 4in-thick solid oak door. The French relied on their armour for defence, but their armour could not compete against such brutal fire-power.

Edward then besieged Calais, starving the city into submission. After nine months of disrupted food supplies, having been forced to eat rats, the besieged population ejected 500 children and the elderly in a last effort to ensure the survival of the remaining adult men and women. The English refused to help the desperate 500 exiles and merely watched as the old and the young slowly starved to death just outside the town walls.

In time, the fight would be passed on to King Edward III’s son, another Edward – better known as the Black Prince – who established his headquarters in Plymouth. In 1348 the Black Prince stayed at Plympton Priory as he prepared his forces for a further invasion of France. However, the Black Death ravaging Devon and France at the time delayed his plans. His father, of course, attributed the spread of the plague to the people’s lack of morality, and not the chaos of continuous warfare!

Not until 1356 could the Black Prince again assemble his invasion fleet – a force of 3,000 men gathered in Plymouth town, which then had a population of only around 2,000. Food and supplies were brought to Plymouth from Cornwall, Devon and Somerset and the Sheriffs of Devon and Cornwall were ordered to supply gangways for the ships and hurdles to corral the horses as they fought their way ashore in France.

Despite initial delays, the Black Prince led his forces to victory in the Battle of Poitiers and captured the new French King Jean II, who was brought back to Plymouth a prisoner. The war-ravaged party escorting the tragic figure of the defeated French monarch on his white horse formed a triumphant procession from Plymouth to Exeter and on to London. Treaties were signed, the French King released, and the Black Prince set up his court at Aquitaine as the French government fell into turmoil. The Treaty of Brétigny in 1360 gave England authority over Aquitaine, half of Brittany, Calais and Ponthieu, though subsequent attempts by the Black Prince to take Paris failed.

The Black Prince capturing the King of France.

The triumph did not last long. In 1372 the King of Castile defeated the English fleet and the English were left with lands only in Calais, Bordeaux and Bayonne. The year before, the Black Prince had returned to Plymouth from failed wars in Spain – he was already a very sick man who would be dead before his father, never to take the throne. Plymouth had played a major role in his triumphs and would mourn his loss. A window in the old Guildhall once celebrated the victories of the Black Prince, but sadly it was destroyed by the bombs of the Second World War.

In 1377 the French attacked again. Edward III and his son were dead, and their successor, King Richard II, was only ten years old. The attacks ravaged Plymouth, leaving it in a state of impoverished decay and ruin, desperate for new defences. The people pleaded to reduce their dues to Plympton Priory in the midst of the devastation. Richard II subsequently assigned monies – from the town’s income, of course, not his own – to strengthen its defences and build a wall around the city under the direction of the Priory – but the wall would not be built in time for the next attack.

The Spanish Castilians were also still a threat to the coastal towns. In the 1380s, Richard II worked with his new Portuguese allies to keep the Castilian galleys out of the Channel while his uncle’s forces marched through Brittany in a failed effort to deliver it from the French. By 1396 Richard II settled for a peace treaty with the French which seems to have lasted until his successor, King Henry IV, came to the throne in 1399. The following year, Plymouth was again under attack.

In 1400 the French commander John of Bourbon attacked Plymouth, on his return from aiding the Welsh in their bid for independence. Bourbon’s fleet chased some trading ships into Plymouth Sound and attacked the town, though this time unsuccessfully. Twelve of Bourbon’s ships were sunk in the harbour and he barely managed to escape with his life. Plymouth celebrated the victory, but worse was yet to come.

The attack by the Bretons in 1403 was the most destructive of all the attacks on Plymouth. It is still commemorated by Freedom Fields, a memorial park established in the town following the battle. On the night of 9 August 1403 thirty Breton ships, manned with 1,200 men, under their leader the Sieur du Chastel, sailed into the dark harbour and anchored in the Cattewater. The Plymouth watch raised the alarm and took their defensive positions. Cannons were dragged to the Hoe and their shot successfully aimed at the Breton ships, but this did not prevent the Bretons travelling further along the Cattewater and landing 1 mile from the town, intending to take Plymouth from the north.

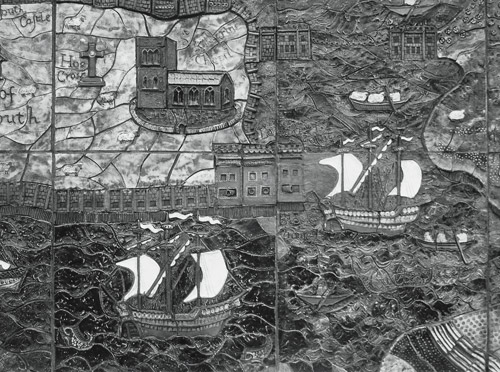

A mural depicting sixteenth-century Plymouth created for the Drake Circus Shopping Centre. The Breton invaders sailed up the Plym River to the east of the harbour, landing at Cattewater, and attacked the old town from the north.

The Bretons plundered and burned 600 wood-built houses on the north-east of Plymouth. Hand-to-hand fighting then broke out in the narrow streets around what is now Exeter Street, but the Plymothians held fast and fought hard against the onslaught of the Breton invaders. Many of du Chastel’s men were killed or captured as they tried to fight their way into the city. By 10 a.m. on 10 August, the Bretons were in retreat, fleeing back to their remaining ships, though with plenty of treasure and a few prisoners of their own.

Since that day, an area of Plymouth to the north-east has been known as Breton (or Briton) side, and Freedom Day was celebrated on 10 August for many centuries after. It was a day of carnival in the classic sense, a licence to drink and re-enact the fights and feuds between the Old Town Boys and the Burton (or Breton) Boys. The victors would be awarded a barrel of beer in Freedom Fields, and the ceremonies were held every year until 1792 – when the festivities were curtailed after the revellers suffered broken collarbones. However, the carnival continued in its own fashion – in 1809 a blind pugilist still held the title of Burton Chief.