Owls Aren't Wise and Bats Aren't Blind (18 page)

Where most other owls content themselves mainly with mice and other small creatures, the great horned regularly seizes rabbits and hares, grouse, crows, weasels, opossums, muskrats, and other prey of similar size. Many a wandering house cat has been snatched by those vicious talons, and the great horned is probably

the

major predator of skunks: evidently lacking a sense of smell, like many birds, the owl seems unfazed by the skunk’s potent olfactory assaults.

I became aware rather early on of the horned owl’s penchant for dining on skunk. At about the age of ten, a friend and I took a correspondence course in taxidermy. We weren’t very good at it, but our efforts with birds came out reasonably well—though only because the feathers covered up a multitude of errors!

In those days, people shot large owls on sight—a practice that was at least occasionally justified, as readers will learn. In any event, someone brought me an exceptionally large great horned owl to be mounted, and the bird reeked of skunk scent. I held my nose, stuffed the owl, and absorbed the information that a great horned owl was willing to tackle rather large prey, including skunks.

There were other things that I knew about great horned owls, as well. I was an extraordinarily fortunate child in many ways. My father and mother lived on my maternal grandparents’ farm while I was growing up. There my parents read to me extensively, while my grandmother, to my great delight, told me a wide variety of stories. Like every child, I loved to hear the same stories over and over, and my absolute favorite was the true story that I called “It Looks Like the Work of an Owl.”

We always had hens on the farm, kept in a hen house at night but roaming freely from dawn to dark. Many years before, hens began to mysteriously disappear. Then one day my grandfather came across the partly eaten carcass of the most recent loss. He examined it carefully and then reported to my grandmother, “Well, Luella (a nickname for Lucy Ellen), it looks like the work of an owl!”

Grandpa set a trap beside the carcass that night, and when he went to milk the cows the next morning, there was the owl in the trap. Grandpa was in a hurry to start the morning chores, so he decided to kill the owl when chores were done. When he returned, however, the owl had departed, leaving one claw in the trap.

Undeterred, Grandpa reset the trap, and the owl—displaying a noteworthy lack of wisdom—was once again in the trap the following morning. This time, Grandpa wasted no time in dispatching the owl! There were no more strange disappearances among the flock of hens thereafter.

Although flocks of free-range hens are relatively uncommon these days, marauding great horned owls can still cause trouble from time to time. A friend who is a cabinetmaker told me about just such an incident that took place not many years ago. His shop was connected to the chicken coop, and one night, while working on some furniture, a great uproar erupted among the hens.

My friend ran outside to the coop’s entrance, and by the light coming into the coop from his shop, he saw a huge owl, wings outspread, clutching a hen. He was afraid to enter the coop for fear the owl might fly into his face, so he poked a broom inside and vigorously swished it around. This disruption soon became too much for the owl, which loosed its hold on the hen and departed in an indignant flurry of wings. The hen recovered, according to my friend, but the attack must have severely traumatized her, for she never laid another egg!

The great horned is the most widely distributed North American owl, inhabiting the continent coast to coast from the Arctic in Alaska and part of Canada far down into Mexico. Despite its wide range, however, the great horned owl is far less common than the barred owl. It’s also seldom seen, not because it’s rare, but because it’s much more nocturnal than the barred owl.

If the great horned owl is less visible than its barred brethren, it’s also far less vocal, both in quantity and variety of calls. Its most common call is a series of deep, resonant hoots, almost always heard at night. It can also utter a series of low hoots that sound almost like the cooing of a dove, although deeper and throatier. Like most owls, the great horned will also hiss when alarmed or upset. Owing to its nocturnal habits and infrequent calls, the presence of this big owl often goes undetected.

The great horned owl fully deserves its reputation as a fierce predator, but this attribute is sometimes exaggerated. For example, one male great horned owl caused all sorts of problems, even attacking humans—quite possibly in defense of a nearby nest. According to various accounts, the owl attacked a twenty-pound dog and flew away with it. The dog’s owner then ran after it, shouting at the owl, which dropped the dog from a height of thirty feet. The dog died; the owl, when later killed, weighed three and a half pounds.

This feat struck me as somewhere between extraordinarily improbable and just plain impossible. Leading ornithologists share my skepticism. As Dr. Stuart Houston, one of the foremost great horned owl experts in North America, put it, “No bird can carry six times its weight.” He and other ornithologists believe that a great horned owl, with its fearsome talons, could kill a twenty-pound animal, but carrying it off is another matter entirely.

A three-and-a-half-pound great horned owl might possibly be able to carry as much as five or six pounds for a short distance—a rather amazing feat for a bird—but certainly not twenty pounds. There was general agreement among the ornithologists with whom I consulted that either the dog weighed a great deal less than twenty pounds or the owl killed it but didn’t carry it off. The great horned owl is an amazing bird, but it doesn’t possess supernatural powers!

The great horned owl has the distinction of being perhaps the earliest nester of any bird throughout much of its range. Nesting may begin as early as January, with snow piled deep on the ground, and it’s not uncommon for the female, superbly insulated by her thick coat of fluffy feathers, to incubate her eggs while covered with a mantle of snow.

Great horned owls possess many skills, but nest building isn’t among them. In forested areas, horned owls most commonly lay claim to an old hawk’s, crow’s, or heron’s nest, but a large tree cavity sometimes serves the purpose equally well. In areas that lack suitable tree sites, the female may simply lay her eggs on a ledge.

Once a nest is established, the female lays one to three eggs, although the usual number is two. Incubation takes about a month. Thereafter, the harried parents are forced to hustle after enough meat to satisfy the rapidly growing appetites of their voracious youngsters. The gawky, homely, fuzzy young grow rapidly and, after about a month and a half, have become sufficiently feathered to fledge and leave the nest. If owls can feel anything like relief, their parents must surely experience it at this point!

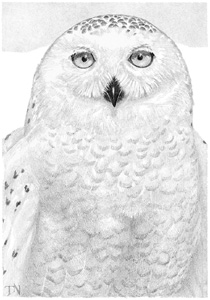

THE SNOWY OWL

This Arctic resident is a birdwatcher’s delight when it descends into southern Canada, the northern tier of states, and, very occasionally, as far south as Florida, Texas, and central California. Why? There are several reasons. First, this is a big, showy owl. With a wingspan of nearly five feet and a weight of four to six pounds, it’s the heaviest of our North American owls. It usually stands out like a beacon when it moves south, because of its imposing size and spectacular plumage—nearly snow white in adult males, more speckled in adult females, and barred with black in juveniles. Further, the snowy owl

(Nyctea scandiaca),

while by no means a rare winter visitor far south of its tundra breeding grounds, is just uncommon enough in many areas to create a stir. Added to all this are the snowy owl’s unusual eyes; whereas most other owls have round eyes, the snowy owl’s yellow eyes are narrowed somewhat, like a cat’s.

Finally, snowy owls have the endearing trait—at least to birdwatchers—of staying in one place for hours on end, usually prominently displayed on a dead stub, a utility pole, or even the top of a building. This is no mere accident: snowy owls evolved as hunters on the vast, barren Arctic tundra, where they prefer to perch on the highest point around and wait until they spot their prey—then glide down to seize their victims by stealth. Thus, when they visit southern Canada and the United States, the big predators favor wide-open spaces (airfields such as Boston’s Logan Airport are often preferred hangouts) and high perches, where they can approximate tundra hunting conditions.

Snowy owls do much of their hunting diurnally. This is no great surprise, considering that there is daylight almost twenty-four hours a day during their high Arctic breeding and nesting season. Conversely, they must also be efficient night hunters during the long stretches of almost total Arctic darkness.

Summer prey for snowy owls consists almost entirely of mammals—mostly small, with lemmings making up the bulk of their diet. In winter, especially for those owls that migrate south, their meals are far more varied. Hares and ptarmigan help carry the owls through the winter in the Arctic, when lemmings are mostly active beneath the snow. Owls wintering farther south have proved quite adaptable when it comes to prey. Mice are a staple, but Norway rats are also prime fare. For that matter, so are pigeons, rabbits, dead fish, and almost anything else of suitable size that comes to the owls’ attention.

It was once thought that these white visitors from the Arctic came south in winter because of a shortage of lemmings. Although it’s a complete myth that lemmings periodically commit suicide by throwing themselves off cliffs into the sea, where they drown en masse, the plump little rodents are notoriously cyclical, going from almost unbelievably high populations to extreme scarcity every four or five years. Unquestionably, lemming numbers have an effect on snowy owl populations, but biologists are learning that the interrelationship between these two species is far more complex than has heretofore been suspected.

Snowy owl

For one thing, there’s no evidence that lemming cycles are synchronized throughout the Arctic, and they may be quite regional. Since snowy owls by nature are great travelers, it’s no special feat for them to move from an area of lemming scarcity to one of abundance. For another, large numbers of snowy owls migrate annually to the Great Plains area of Canada and the United States without apparent reference to lemming cycles. Much remains to be learned about the dynamics of the lemming/snowy owl relationship.

Snowy owls are silent for most of the year. During the breeding season, however, they utter a variety of sounds, especially a croaking call and a sort of shrill whistle. They may hiss when they or their nests are threatened, and reputedly also hoot during the breeding season.

Prior to breeding, snowy owls perform a fascinating courtship ritual. First comes the flight display, in which the male alternately descends with wings arched above his back, then flaps upward, only to repeat the procedure. Then he begins to bring lemmings, which he deposits in a pile in front of the female; this performance may signal that he’s a good provider, that prey is sufficiently abundant to enable the parents to raise a brood successfully, or both. Finally the male goes through a variety of strange poses and then fawns in front of the female to complete his amorous display.

Like the rest of their tribe, snowy owls aren’t nest builders. On a hummock or other high point, the female simply scrapes out an unlined hollow and begins to lay eggs. It’s noteworthy that such a location provides not the slightest protection from the bitter Arctic winds, but allows the nesting pair to watch for predators in every direction. Protection from the wind evidently isn’t important to snowy owls, for their magnificent plumage has the same insulating power as that of Antarctic penguins and enables them to withstand the horrific cold of an Arctic winter.

At this point the species’ nesting behavior becomes highly unusual. Snowy owl clutches range from the merely very large—for owls—of five to eight eggs to the huge, with as many as sixteen. The exceptionally large clutches are thought to occur only in years when lemmings are extremely abundant, but that’s by no means certain. What is certain is that the female lays one egg roughly every two days, yet she must begin incubation as soon as the first egg is laid, lest it freeze solid in the frigid Arctic weather. If she lays a dozen eggs, this means that nearly a month elapses between laying the first and last eggs in the clutch. Each egg takes about thirty-two days to hatch, so the last egg has barely been laid by the time the first one hatches!

With the nest on the ground, the fuzzy gray owlets don’t have to fledge in order to leave it. They merely step out of the nest, long before they can fly, and nestlings from the early eggs walk away soon after siblings from the later eggs have hatched. The owlets move about, but remain near the nest, where the male brings them food. The female is tied to the nest until the last owlet leaves, which can be two months in the case of a very large clutch.

Snowy owlets fly about seven weeks after hatching, so raising an exceptionally large brood, from the time the first egg is laid until the last owlet takes wing, can consume more than three and a half months. Since that represents virtually the entire Arctic summer, the process of raising such a large brood places an enormous strain on the adult pair, particularly the male, who must do all the hunting while the female is laying and incubating the eggs. Adult snowy owls consume as much as four or five lemmings a day, and the appetites of their young grow daily, so it’s been estimated that a pair of adults with a brood of, say, eight or nine can devour more than 2,500 lemmings in a single Arctic summer!