Owls Aren't Wise and Bats Aren't Blind (15 page)

10

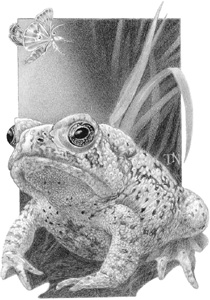

The Lowly One: The Common or American Toad

MYTHS

Handling a toad can give you warts.

Handling a toad can give you warts.

Toads are ugly, nasty creatures.

Toads are ugly, nasty creatures.

A toad urinates when it’s picked up.

A toad urinates when it’s picked up.

HOW SHALL I LOATHE THEE, LET ME COUNT THE WAYS.

Pity the poor toad. Down through the ages this inoffensive and beneficial little creature has been regarded at best as downright ugly and at worst as vile and loathsome. Even frogs have fared far better: they, at least, have been accorded the possibility of reconversion to handsome princehood via the kiss of a benevolent and presumably beautiful princess. Alas, no similarly pleasant fate has ever been recorded for a toad! Even Kenneth Grahame, in his classic

The Wind in the

Willows,

portrays Mr. Toad as a bumbling, conceited ass, albeit a well-meaning and generally likable one.

The much-maligned toad has even been associated with evil and the demonic. In the first scene of Shakespeare’s

Macbeth,

for instance, the witches depart when they say, “Paddock [a term for the toad] calls. . . .” Then, in the famous cauldron scene, in which the witches brew their “hell-broth,” they throw into the potion “Toad that under cold stone, days and nights has thirty-one. . . .” And in

As You Like It

we find the phrase “like the toad, ugly and venomous.”

Nor was Shakespeare the only one to defame the unfortunate toad. For instance, the poet Philip Larkin penned the line, “Why should I let the toad

work

squat on my life?” Even in everyday language we indirectly heap scorn on the little creature: a

toady

is defined as a cringing, servile person, and a despised individual may be referred to contemptuously as a toad.

Common (American) toad

In speaking of “toads” here, only three species are involved. Shakespeare was undoubtedly writing about the common toad of Great Britain

(Bufo bufo),

and this chapter is mostly devoted to the common or American toad

(Bufo

americanus),

which is nearly identical to the British common toad. Woodhouse’s toad

(Bufo woodhousii),

also known in the West as the “common toad,” is likewise quite similar to these two. There are many other toads, however—approximately three hundred species worldwide and eighteen species in North America—a number of them vastly different from the common toad. Many of the North American species are in the Southwest, but the misnamed horned toad isn’t one of them; rather, it’s a little lizard, spiny-looking but harmless.

As if the nasty things already cited weren’t sufficiently defamatory, further indignity has been heaped on the toad by accusing it of causing warts—a folk superstition that many still believe. Toads, of course, have nothing whatever to do with human warts, which are caused by a virus. The toad’s so-called warts are not warts at all, but glands that have a defensive purpose. These glands, especially the two large ones behind the eyes, give off a slightly poisonous substance that makes the toad quite unpalatable to many predators.

This poison is far too mild to harm humans who handle toads, although it might sting a little if it gets into a person’s eyes. Therefore, it’s advisable to wash one’s hands after handling a toad—but not because of any danger of warts! Incidentally, those two large glands behind the toad’s eyes are sometimes mistakenly referred to as parotid glands. Parotid glands are salivary glands in mammals; the toad’s two prominent glands are properly called

parotoid

glands (pronounced

pah-ROH-toid.

)

If one examines a toad carefully, with an open mind, the creature ceases to be ugly and exhibits some rather attractive characteristics. On closer inspection, its seemingly drab exterior becomes a handsome mosaic of colors on the upper side, ranging from tan to terra cotta to rich, dark browns, while black and shades of gray lend further variety to this pattern. The underparts, by contrast, are a nice cream color with some black spotting. In addition, the toad’s gold-rimmed eyes are very lovely. Despite its squat shape and warty appearance, the common toad is far from ugly!

Centuries of bad publicity notwithstanding, toads are extremely useful creatures. They consume large quantities of insects, slugs, and other creatures that can seriously damage vegetables and other desirable plants. Therefore, toads should be considered a welcome addition to anyone’s grounds or garden, and encouraged in any way possible.

Fortunately, the toad’s sterling qualities are finally being recognized. In England, for example, there is Madingly Toad Rescue, an organization named for the village of Madingly. Owing to heavy traffic, toads were being killed wholesale as they crossed highways in an attempt to get to or return from their breeding ponds. To save dwindling toad populations, Madingly Toad Rescue was formed by concerned citizens.

With experience, this organization has developed several effective techniques for saving toads. For instance, construction of amphibian tunnels under the highways has worked very well. However, the most successful method has been for volunteers to pick up the migrating toads, put them in buckets, and move them to the other side of the highway. Volunteers have also been aided in this endeavor by temporary net fencing, which funnels and concentrates the toads so that they can be located and picked up more easily.

While appreciation of toads tends to be a bit less dramatic on this side of the Atlantic, gardeners and homeowners have increasingly come to understand the benefits of a healthy toad population. Indeed, modern gardening books often emphasize the value of toads, and gardening supply catalogs feature little toad shelters that can be placed in gardens and around homes to attract these helpful tenants.

Toads are amphibians, with all that the term implies. The word is derived from the Greek

amphi,

of two kinds, and

bios,

life, and refers to the fact that toads and other amphibians can live both on land and in the water. Indeed, water or a very moist environment is required for amphibians to reproduce, although many spend most of their lives on dry land.

Amphibians are a truly ancient race. They alone, among primitive vertebrates, first crept out of the primal waters to set foot on land some 360 million years ago—an almost unimaginable span of time. This was at the beginning of the Carboniferous period, when plants such as the giant tree ferns flourished in immense profusion, eventually to be transmuted into coal beds by the labors of eons.

This was no small step for life on our planet. Up to that time, all vertebrates were aquatic; this transition, which might be termed the Great Leap for vertebrates, was truly monumental, because it paved the way for the development of all vertebrate life on earth. Radical evolutionary changes were vital in order to make this momentous transition from aquatic to terrestrial environment. The ability to obtain oxygen from the air was critical; this required the development of lungs and moist skin that could absorb oxygen. Limbs that could support these new creatures on land and enable them to move about were also necessary.

Without other vertebrate predators, at least for a very long time, these early amphibians were able to prosper and evolve further. Still, this evolution was incredibly slow in terms of our human time frame. The earliest known ancestor of toads and frogs, barely recognizable as a very primitive prototype, dates back to the early part of the Triassic period, about 240 million years ago, or 120 million years after the first amphibians appeared. A mere 50 million years or so later, in the early Jurassic, evolution had proceeded apace and produced what could reasonably be termed the first recognizable frog. To put this development in perspective, the earliest true frog evolved even before most types of dinosaurs!

Ancient times were the heyday of amphibians, which comprised perhaps fifteen major groups at their peak. However, the development of reptiles, followed by birds and mammals, provided serious competition, and amphibians slowly declined. Today there are just three remaining orders of amphibians—frogs and toads, salamanders, and caecilians, a group of wormlike tropical creatures.

In a sense, amphibians represent a sort of arrested development. Unlike the reptiles—which, incidentally, evolved from an amphibian ancestor roughly 315 million years ago—amphibians never took that final step to become completely terrestrial. Although many reptiles, such as turtles and crocodilians, spend most of their time in the water, all reptiles (except for some sea snakes) bear their young on land, and many are completely terrestrial.

Reptiles were able to accomplish this transition by developing eggs that wouldn’t dry up on land and skins that greatly reduced the loss of water. In contrast, the soft, gelatinous amphibian eggs are useless out of water, and amphibians themselves can only withstand hot, dry conditions by protecting themselves in a moist environment. Perhaps the enormous early success of amphibians was a mixed blessing, halting further development so that amphibians remained in a sort of evolutionary limbo, neither fish nor fowl, so to speak.

The question sometimes arises, what is the difference between frogs and toads? From a strictly scientific point of view, there’s hardly any difference. Frogs have teeth in their upper jaw, whereas toads lack them, but otherwise the distinction between toads and frogs is largely an artificial one for purposes of convenience.

Most

toads have dry, rough skin, a plump body, and short legs best suited for hopping.

Most

frogs, on the other hand, have smooth, moist skin, a fairly slender body, and long legs well suited for leaping. However, there are frogs with rough skin and toads with smooth skin, for example, so frogs and toads can’t be differentiated simply by appearances.

There has been a great deal of concern among scientists because of a recent worldwide decline in some species of frogs and toads. Various theories have been propounded for this decline, ranging from pollution to an increase in ultraviolet rays from sunlight, but no definite conclusions have been reached. Fortunately, the common toad seems to be maintaining its numbers.

Life for toads (or frogs) begins in the water. After emerging from hibernation in March or April—or even in May, depending on the climate—male toads make their way toward suitable breeding areas, such as shallow marshes, ponds, and pools. There the males begin to sing, a loud, high trill that can continue uninterrupted for as much as thirty seconds. This sound is produced when the male inflates his vocal sac and vibrates it during the course of the call. The sound of trilling toads at a discreet distance is a welcome sign of spring, but a number of males trilling simultaneously at very close range can be almost deafening!