No Pain Like This Body (2 page)

Read No Pain Like This Body Online

Authors: Harold Sonny Ladoo

Tags: #Historical, #Literary, #Fiction, #General

In the ancient text the Ramayana, Rama is wrongfully sent into exile from Ayodhya. He spends fourteen years fighting various battles, the most crucial to reclaim his wife, Sita, from the demon king of Lanka, Ravana and he returns in triumph to Ayodhya to sit as its rightful king. On his return the people light deyas along his way welcoming him home. That epic myth arrived in the diaspora with indenture workers. It was perhaps a source of sustenance throughout their own exile. A return garlanded in the lights of welcome awaited them after the bleak drudgery of a life tied to plantations of cane and rice.

This epic lies somewhere in the text of

No Pain Like This Body.

But no garland of lights precedes or follows Ladoo's Rama. A fever burns in him, he is stung by scorpions and eventually carried even farther away from mythic Ayodhya. The lights that preceded Rama were supposed to remove darkness not only from homes but also to banish ignorance and hatred from hearts. Ladoo renders a Ramayana steeped in hatred and violence. Plagued by incessant rain (“the rain fell like a shower of poison over Tola”) and a god terrible and indifferent (“God does only eat and drink in that sky”), Ladoo's onomatopoeic insistencies make more horrifying the action in the novel. His characters' trusting innocence, their supplication to fate are made more disastrous by his feats of verbal play. Told through the view of a child, nature and human beings are overwhelmingly brutal.

“Better than a thousand verses, comprising useless words, is one beneficial single line, by hearing which one attains peace.”

These words uttered by the Buddha possibly describe Harold Ladoo's contribution to both Caribbean and Canadian literature. How can I say this of a novel so unrelentingly brutal. Because

No Pain Like This Body

is a novel that strips its reader of sentiÂmentality of any kind â pity or superiority. It is a novel unconcerned with anything but truth-telling. And because peace is nothing without the truth, I suspect for Ladoo this was obviÂous. So much of his life had been spent in truth's bald presence that he was able to capture it in his brief time.

â Dionne Brand March 2003

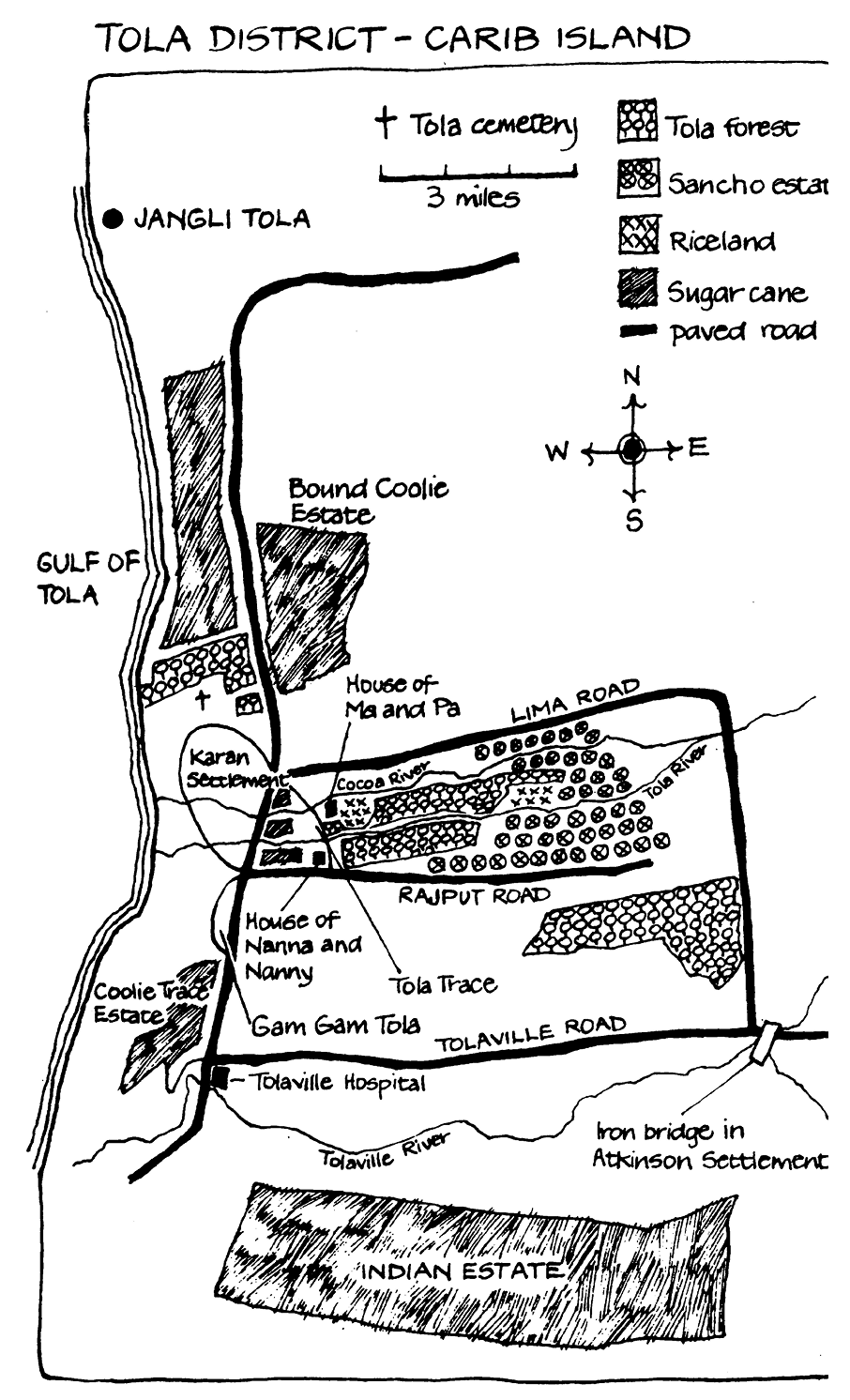

TOLA TRACE

August, 1905

CARIB ISLAND

Area: 1000 square miles.

History: Discovered by Columbus in 1498. Taken over by the British in 1797. East Indians came to Carib Island to work on the sugar plantations from 1845 to 1917.

Chief Exports: Sugar, petroleum, rum, cocoa, coffee, citrus fruits and asphalt.

(Also see Glossary)

I

PA CAME HOME

. He didn't talk to Ma. He came home just like a snake. Quiet.

The rain was drizzling. Streaks of lightning like long green snakes wriggled against the black face of the sky. Balraj, Sunaree, Rama and Panday were in the riceland, not far from where Ma was washing clothes. The riceland began about ten feet away from the tub. Balraj was trying hard to catch the tadpoles; they were black black, black like rain clouds, and they were moving like spots of tar in the water. Balraj was the oldest. He was twelve. He tried hard like hell to catch the tadÂpoles and put them in the ricebag. But the tadpoles were smart, smarter than Balraj. They behaved like drunk people in the water; they were giving a lot of trouble; they kept running and running in the water; they had no legs, but they were runÂning in the muddy water; just running and running away from Balraj. Balraj wanted to catch the tadpoles so he kept on running behind them; and they knew that Balraj wanted to put them inside the ricebag, so they ran all the time away from him.

Sunaree was ten years old. She was dragging the ricebag in the water, just behind Balraj. But Balraj was getting fed up. The tadpoles were hiding away from him.

Rama and Panday were eight years old. Twins. They were naked. Both of them were running behind Sunaree. As they ran they kicked up water and soiled Sunaree's dress. Sunaree turned around. She was vexed and her face looked like a rain cloud. Then she said, “Now Rama and Panday behave all you self!”

While she was talking to Rama and Panday, Balraj dragged his hands in the water to catch the tadpoles. He lifted his hands out. There were about ten tadpoles inside them. They were trying to jump out of his hands and go back into the water. Balraj turned around to put the tadpoles in the ricebag. Sunaree was not paying attention; she had the bag in the water, and she was talking to Rama and Panday. Balraj got mad; he bawled out, “Sunaree I goin to kick you! Where de bag is?”

“De bag in de wadder bredder.”

“Wot it doin in de wadder?”

“It not doin notten.”

“Well pick up dat bag and open it.”

“Oright.”

Sunaree had a great love for the tadpoles also, so she opened the ricebag. Balraj dropped the crappo fish inside the ricebag, and bent down in the water again.

Rama and Panday walked up to Sunaree. They were not walking easy as a fly walks; they were walking like mules; feet went

splunk splunk splunk

in the water.

“Rama and Panday all you walk easier dan dat,” Balraj told them. “Dese crappo fish smart like hell. Wen dey hear all you walkin hard hard dey go run away.”

Rama and Panday didn't listen to Balraj. They held on to the ricebag. They opened it and peeped inside the bag. Their eyes were bulging like ripe guavas; they were trying hard to see the tadpoles that were in the bag, but they could not see anything. Rama sucked his teeth and said, “I want to go in dat bag.”

Sunaree told him he couldn't go inside the ricebag, because he was going to kill the tadpoles.

“I want to go in dat bag too,” Panday declared.

“But I say all you cant go in dat bag. All you goin to kill de fish.”

Rama and Panday tried to pull the ricebag away from Sunaree. She was talking and begging them not to pull the bag; crying and begging them not to pull it away; crying not for her sake but for the tadpoles' sake, because she wanted the crappo fish to live. But Rama and Panday pulled the bag away from her.

Balraj walked in the water. His back was bent as if he was an old man. He knew that the tadpoles were smart, so he watched them carefully. There were some crappo fish near the bamboo grass; there were hundreds of them; they were dancÂing and moving like a patch of blackness. Balraj walked quietly. He moved closer to them; they did not see him, because they were dancing in a group. He bent down. Slowly. He stretched his hands. Then

wash wash

his hands swept through the water. He turned around to put the tadpoles in the ricebag. Balraj just turned around and dropped them inside the bag. But there was no bag; the tadpoles fell back into the water. Balraj just stood and looked and looked at the tadpoles that were free again in the water, then he got mad like a bull. He looked. Rama and Panday were dragging the bag in the water.

“Wot de hell all you Join wid dat bag?”

“We just playin bredder,” Panday said.

“Now all you drop dat bag!”

Balraj couldn't control himself. He ran up to them just like a horse. Rama and Panday dropped the bag in the water and started running towards the cashew tree.

Sunaree saw Balraj coming like a jackspaniard. She did not know what to do, so she just stood there and stared at Balraj. “Why you give dem two son of a bitches dat bag?”

“I not give dem it.”

“Den who give dem it?”

“I tell you dey take it deyself.”

Sunaree had long black hair; it was thick like grass. Balraj grabbed her hair and started kicking her in the water. She pushed Balraj, and he fell

splash

in the water. Sunaree wanted to run away, but she couldn't run away; Balraj grabbed her hair again; he was pulling her hair as if he was going to pull out her head. Then he started dragging her in the muddy water.

Balraj couldn't see Pa at all. Pa just stood in the banana patch like a big snake and watched all the time. Ma was busy, washing the clothes; she couldn't see Pa either. Pa was just hidÂing and watching with poison in his eyes. Ma was just washing the clothes under the plum tree. Her back was bent low over the tub, and she was washing as if the clothes were rottening with dirt; she just bent over the tub and scrubbed like a crazy woman. Then she heard Sunaree bawling. Ma lifted her head. Balraj was still dragging Sunaree in the water.

Ma shouted, “Leggo dat chile Balraj!”

“I not lettin she go!”

“Boy I is you modder. I make you. You just lissen to me. Leggo she.”

“I not lettin she go!”

“I comin in dat wadder for you right now Balraj!”

Ma was fed up. She washed out her hands in the soapy water. Then she walked to the edge of the riceland. Ma was quarrelling and pointing at Balraj. Suddenly she stood up. She saw Pa. Ma turned around and walked back to the tub.

Pa came out of the banana patch.

“Now all you chirens come outa dat wadder!” he shouted. Pa had a voice like thunder. When he spoke the riceland shook as if God was shaking up Tola.

Rama and Panday were near the cashew tree. They were trying to hold the mamzels, but they moved like the wind. “Let we catch dem crabs,” Rama suggested.

“And do wot wid dem?” Panday asked.

“Kill dem.”

“It not good to kill notten.”

They had to be careful in the riceland. There were deep holes all over the place, especially near the cashew and barahar trees. The holes were not deep like a well or a river, but they were deep enough to drown Rama and Panday.

“It have crabs near dat barahar tree,” Rama said.

“It too deep by de barahar tree,” Panday told him.

“It not too deep. Dem red crabs livin in dem holes.”

“But dem holes deep deep.”

“I still goin to walk to de barahar tree,” Rama declared.

Rama began walking eastwards across the riceland. Panday was begging him not to go, but Rama was not listening; he was harden like a goat. But Rama couldn't go. He and Panday heard when Pa shouted at Balraj and Sunaree. Panday and Rama ran out of the riceland, passed through the banana patch and went by the rainwater barrel. The rainwater barrel was almost touching the tapia wall at the eastern side of the house.

When Pa shouted, Balraj released Sunaree. She ran out of the riceland, passed Ma by the tub and went and joined Rama and Panday by the rainwater barrel, but Balraj remained inside the riceland. He stood up and looked at Pa; he was watching as if he was going to eat Pa; he was really playing man for Pa. Pa made an attempt to go in the water. Balraj was afraid; he ran to the eastern side of the riceland. He ran as fast as a cloud moves in the sky. Then he stood up on a meri on the other side of the riceland and looked at Pa.

“Now Balraj come outa dat wadder!”

“I fraid you beat me.”

“I not goin to do you notten boy.”

“Oright.”

Pa was smarter than a snake; he began to talk soft as if a child was talking. He said that he was not going to beat Balraj, because he was a child. He thought that Pa was talking the truth; he began to walk to meet him. Pa just stood there and looked at him; just stood on the edge of the riceland and waited as a snake.

Balraj walked slowly. His feet didn't go

splash splash

in the water; they went

splunk

and

splunk

and then

splunk

as if a litÂtle child was walking in the water. He watched Pa with fear in his eyes as he came closer to the western edge of the riceland. Pa wasn't backward; he was watching Balraj with snaky eyes. The wind was blowing cold cold. Balraj was trembling. His teeth went

clax clax clax.

The wind was blowing from the north. It was cold as ice cream, and Balraj was trembling and watching Pa. The sky was black as Sunaree's hair, and Pa was watching Balraj. Balraj was almost out of the water. Pa leaned over the edge of the riceland and tried to hold his hand. Balraj ran

splash splash.

Pa ran eastwards along the rice-land bank; his feet went

tats tats tats.

There were many snakes in the riceland; they lived inside the deep holes near the barahar tree. Balraj was trying to keep away from the holes, because he was afraid of the snakes. Balraj was tired running. He just stood in the water and looked at Pa. Pa was mad. He jumped up and down on the riceland bank.