My Guantanamo Diary (29 page)

Read My Guantanamo Diary Online

Authors: Mahvish Khan

The world will find out the truth about Guantánamo. One day they will read about it in history books. They will watch it in movies. This is very bad for America that they are doing this. May God show them the right path and some humanity.

The problem with the American government is that their decisions are twisted. They are driven by greed. They follow their stomachs, they follow oil, and where they can make the most money. And then it is the poor Afghans who suffer at your hands. We were very happy when the Americans first came. We considered you our friends from the time of the Russians. But then the bombs began to fall from the sky. They shattered what was left of our poor country and imprisoned us without charge or evidence.

Is America really in a position to be establishing democracies? They have much they need to change about themselves first. I am not saying that all Americans are bad. Please don’t get me wrong. There are good among us all. But, there are two people in this war on terrorism who have gotten a bad name: The Americans and the Taliban.

All the detainee meetings left me feeling helpless. The men I met showed me the human face of the war on terrorism.

Though they were systematically dehumanized, to me they became like friends, or brothers, or fathers and uncles. I often see their faces in my dreams at night.

Once I dreamed that my father, Baba-jaan, was at Gitmo. He was being led away out of Camp Echo by two guards. I don’t remember what he was wearing, but like all the others, he put on a brave face and called out to me, “I love you,

bachai

—my daughter.” I stood there at a loss as he disappeared. I thought of that dream when I saw the Afghan men in their cages. Any one of them could have been my dad, or somebody else’s.

I can honestly say that I don’t believe any of the Afghans I met were guilty of crimes against the United States. Certainly, some of the Guantánamo detainees were, just not the men I met. Some might have been allied with Afghan warlords, and some might have worked under the Taliban. Perhaps, had I met some of these prisoners in Afghanistan five years ago, they would have wanted to cane me for not covering properly. But there was no evidence they had committed crimes under U.S. law.

I wish we could have just handed most of them the freedom they so desperately craved.

Tehran, October 12, 2006

The phone rang at a little after 3

PM

. Waheeda knew at once that

it was good news. Her brother-in-law, Ismael, was calling from

Gardez, giddy with excitement.

“Doctor Sahib is coming home today, inshallah!” he exclaimed.

He’d just heard a public announcement: a group of Afghan prisoners

would be arriving from Guantánamo later that day. Among the sixteen

names was that of her husband, Ali Shah Mousovi.

Even as Ismael’s message echoed through Mousovi’s Tehran home,

the doctor was aboard a plane headed east, toward home. Blindfolded

and shackled, he pictured his family in his mind and wondered

what it would be like to see them after so long. The minutes

seemed endless.

Then, at last came the vibrations of wheels descending and locking

into place and the aircraft gliding down the tarmac of Bagram

Air Force Base. Mousovi heard the cabin doors being opened.

One by one, the men were led off the windowless plane, loaded into

vehicles, and driven about thirty miles south to Kabul. There, American

soldiers handed them over to the Afghan Peace and Reconciliation

Committee, a Kabul-based organization headed by former

Afghan president Sibghatullah Mujadidi. Their blindfolds and shackles

were removed. The men said a prayer together, and afterward,

some spoke with journalists and Afghan officials. When it was

Mousovi’s turn, he stood up but found himself at a loss for words.

“Someone who has spent four years only speaking to walls—it is

difficult for him to talk in the presence of leaders,” he began. “You

must be assured that all those sitting here and most of those still in

Cuba, none of them have done anything to deserve [what happened

to them in] Cuba.” Most had nothing to do with terrorism, he said.

They had been turned over, because of tribal, ethnic, religious, and

political animosities, to the American military who “without any investigation,

arrested people and put them in jail.”

1

After a short ceremony, the former detainees were reunited with

family and friends who stood waiting outside. Still wearing their

Gitmo prison garb, the weary but contented men walked quickly into

the arms of their loved ones.

Ali Shah Mousovi scanned the crowd for his brothers’ faces. When

he spotted them, they began to cry.

“Those were the hardest years of our lives,” one brother who lives

in Washington, D.C., told me later. “I will never forget that day. I

cried like a baby when I saw him there.”

From Kabul, Mousovi was whisked to Gardez, where he was

given a hero’s welcome by crowds of well-wishers who had flocked

from neighboring towns for his homecoming.

“There weren’t any gift shops at Guantánamo Bay,” Mousovi

joked. “All I have is this prison uniform, if you want it!”

In fact, Mousovi said he would probably keep the uniform for the

rest of his life. His brothers, however, urged him to trim the beard he

had grown in Cuba and dye it black again. Mousovi was hesitant,

but his brothers knew that it would be good for him, particularly before he saw his wife and children

in Iran. He finally agreed, and

with his beard shorn close and

dyed black, he instantly looked

decades younger.

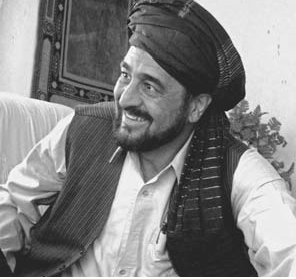

Ali Shah Mousovi at his Gardez home.

That evening though, his

brothers watched with concern

as he lay down to rest and curled

his body into a defensive, almost

fetal position. It was very unlike

the relaxed way he had always

slept before.

Once arrangements were made, Mousovi was off to see his family in

Iran. His homecoming was not a small family affair. Dressed in a tan

suit, he was greeted at Tehran International Airport by hundreds of

well-wishers and journalists. The crowds flocked around him;

friends, neighbors, and locals placed flower garlands around his neck

and congratulated him.

Crowd of well-wishers

greeting Ali Shah Mousovi

at Tehran International

Airport.

Courtesy of Dr. Ali

Shah’s family.

Ali Shah Mousovi with daughter, Hajar, at

Tehran International Airport.

Courtesy of

Dr. Ali Shah’s family.

Dr. Ali Shah with his mother at

Tehran International Airport.

Courtesy of Dr. Ali Shah’s family.

Abu-Zar cut through the crowds and reached out for his father.

Mousovi did a double-take, looking at his eldest boy, now a tall lanky

teenager with a beard. After that initial look-over, Abu-Zar remained

glued to his father’s side. And then, one by one, the doctor and his

teary-eyed family embraced.

Mousovi’s younger son, Kumail, ran around with a camcorder,

recording the end of a bitter chapter in the family’s history. Paparazzi

followed as the family slowly made its way out of the airport

and Mousovi stopped in front of a waiting car to speak to the

crowd of onlookers and local news reporters who had gathered

around him.

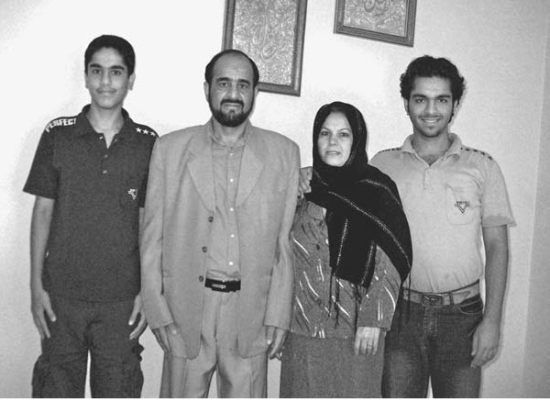

Ali Shah with his two sons, Kumail and Abu-Zar, and his wife, Waheeda, at their

Tehran home a few months after his release.

Courtesy of Dr. Ali Shah’s family.

“I am returning from prison. I don’t have stories of adventures or

vacation. I have nothing exciting to speak of. I was a prisoner. There

are many more just like me. Unfortunately, we all saw only hardship,”

he said.

Then, he and his family got into the car and drove off.

When I visited Afghanistan in the winter of 2006, Mousovi was

still in Iran, but we spoke once in a while by telephone. “It’s so great

that I can pick up a phone and call you now, Doctor Sahib,” I told

him in one of those calls, addressing him with a term of high regard

and admiration.

“I will never forget the love you showed me while I was a prisoner,”

he said. “I hope to see you one day soon in Afghanistan.”

When I went back to Afghanistan a year later to collect affidavits

and exonerating evidence for my client, Hamidullah al-Razak, I was

happy to learn that Ali Shah Mousovi was there too. He’d come from

Iran to house-hunt in Kabul, to finally set up his clinic and build a

life for his family in their war-torn country.