My Guantanamo Diary (25 page)

Read My Guantanamo Diary Online

Authors: Mahvish Khan

THE POLICE CHIEF

Abdullah Mujahid thought that the feminist movement had shortchanged American women. Once they were loved just for being “nurturing mothers and wives, precious sisters, and little girls.” But now, Mujahid perceptively noted, women in our country carry an ever-growing load of responsibilities; in addition to caring for a family, they’re expected to work.

“If a woman chooses to work because she likes and wants to, she should,” the thirty-five-year-old Afghan detainee said to me and Carolyn Welshhans, a lawyer from Dechert’s Washington, D.C., office, at a meeting in March 2007. “But women shouldn’t have to get jobs. We are happy to take care of our women, protect them. And women in my country are happy to depend on their husbands and fathers.”

It sounds good. But as I listened to Mujahid, I thought that “depend” was the wrong verb. Afghan women don’t just “depend” on men; they’re at men’s mercy. Men dictate when and whom a woman may marry, how she may dress, with whom she may interact, and whether she’ll ever be able to read a book or write a letter. But I kept all of that to myself because I sensed that Mujahid was gently trying to bridge our worlds and paint a better image of his countrymen for the two women from America.

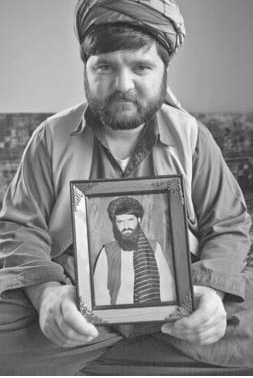

Farid Ahmad holds his brother

Abdullah Mujahid’s framed

photograph; Gardez, Afghanistan.

Jean Chung/WPN for

Boston Globe.

We didn’t have our first real conversation with Mujahid until our third meeting with him. He was a strongly built man with closely cropped hair without a single strand of gray. He was well mannered and gracious, like Dr. Ali Shah Mousovi, but somehow reserved and slightly guarded. The first time I met him, I assumed, because of his strong physical presence, that he would take control of the meeting, but in fact he said little. He only politely answered questions, never steering the discussion or even hinting at an initial mistrust, as most prisoners do. So, the afternoon of our third meeting in Camp Iguana was unique.

“Afghan men really believe that women should spend their lives comfortably. We love our mothers and wives,” Mujahid said. “They’re so delicate, and they need someone to protect and care for them. There’s nothing wrong with this. I just don’t think women should have to worry about feeding their families and making money.”

“What if they enjoy working, like we do?” Carolyn gently challenged him.

“There’s nothing wrong with a woman working, but being forced to . . .” Mujahid’s words trailed off, as if he were about to say that it would be like child labor.

Still, I thought to myself that an Afghan women’s movement would at least give girls the right to an education. And Mujahid agreed. Before his July 2003 arrest, he had been the police chief of Gardez, the same town from which Dr. Ali Shah hailed. When I visited Afghanistan, I met an official from the Ministry of Education who described Mujahid as a zealous supporter of girl’s schools. In fact, as soon as the Taliban were pushed out of Gardez, Mujahid had financed the construction of numerous schools for girls out of his personal savings, then spent time encouraging hesitant parents to enroll their daughters.

Mujahid was curious about how Americans perceived Muslims and Afghans and whether the young blond lawyer sitting before him had any prejudgments of her own.

“What did you think about Muslim men before you came here?” he asked Carolyn.

“Actually, the first Muslims I ever met were at Guantánamo Bay,” she told him, “and the experience has completely opened my eyes.”

He asked how.

“I was a little apprehensive before I came,” Carolyn told him. “I didn’t know what to expect. But every prisoner has treated me with dignity, respect, and kindness.”

Carolyn admitted that she had once lumped all Gitmo detainees together, as an indistinguishable mass of numbered

Muslim men. While she felt that they deserved representation, she had come in with a headful of biases.

“I was afraid of being rejected as an American and as a woman,” she admitted.

Mujahid nodded. “The problem,” he said, “is that the Taliban’s short rule of Afghanistan has given all Afghan and Muslim men a horrible name. But the Taliban and what they did to our country does not offer a true picture of Afghanistan or of Afghan men. It was a terrible time for us, and anyone who had the money fled.”

“You’re right,” Carolyn said. “And as I got to know each prisoner here, one by one, they’ve chipped away at my biases. With every prisoner I met, I realized that each was a unique individual. Every man was as different from the next as any two people could be.”

She described how Abdullah Wazir Zadran, a good-looking twenty-eight-year-old Afghan shopkeeper from Khost, reminded her of her younger brother Jeff, who was the same age and had the same light brown eyes.

“Jeff is younger than I am, and we’re very close,” she said. “Seeing Zadran chained to the floor made me think of my brother and that it could have been him, thousands of miles from home, without access to his family, friends, or a fair hearing.”

The boyish-faced shopkeeper was Carolyn’s only client younger than her, as well as the only one who tried to boss her around. Sometimes, after some discussion of what was going on in Afghanistan or the legal issues in his case, Zadran would get a bored look on his tanned face and start telling Carolyn to do something, insisting that she bring him a book after lunch,

for example. Even after she explained that books had to go through a clearance process, he would keep right on insisting.

Carolyn wouldn’t get offended. She knew he was just being stubborn and trying to do things his own way. It was the kind of thing that reminded her of her younger brothers. “Although,” she said, “they both know better than to boss me around.”

The first prisoner Carolyn had met, therefore the one who left the strongest mental impression, was Abdul Haq Wasiq.

“He was the first I ever saw chained to the floor,” she recalled. “He was the first to thank me for being a humanitarian. He was the first to refuse to meet with me when I visited again. He was the first to then change his mind again—and meet with me on another trip. He was also the first to use the word ‘torture’ in reference to how he was treated. He was the first to indicate how badly Guantánamo was affecting him psychologically.”

The words of Dr. Hafizullah Shabaz Khail, a sixty-one-year-old Afghan pharmacist from Gardez, haunted her. “If you free one Afghan, it will be like you are bringing someone back from the dead,” he said.

Meanwhile, Mohammad Zahir, a fifty-four-year-old Afghan schoolteacher from Ghazni who was badly in need of dentures, impressed her with his dry sense of humor. “Mohammad Zahir is as lonely, depressed, angry, hurt, and devastated as our other clients,” Carolyn said. “He is very worried about his family. But we also have ended up laughing at least once in each of our meetings, and I think it said a lot about him that he still tries to laugh—even if most of the time he is laughing at me. Every time I meet with him, I worry that his spark will have gone out, but so far he has managed to hold onto it.”

“All of the men I have met here,” she told Abdullah Mujahid, “have treated me with respect and kindness.”

“Religious freedom was something I always believed in,” she said, “but now when I hear people speaking critically of Muslim men and Islam, I have a point of reference for disagreeing. I can now say that it is not consistent with my friend Abdullah Mujahid or Abdullah Wazir Zadran or Mohammad Zahir. I know these men, and I know they are good people with good hearts.”

Mujahid listened. “I think the problem is that Americans are very removed in many ways from the Muslim world,” he said finally. “There is a perception that Muslim men will gobble people up—that we are all terrorists. The West fears the Muslim world because of the actions of a few bad people, and those bad people are considered just as evil in the Muslim world as they are in America.”

Really, we are more alike than different, Mujahid said. “If Americans could sit down with Muslims and get to know them, they would see how similar we are. We are just like you. We love our families. We want the best for our children. We want peace in our country. We want a future to look toward.”

Again, he emphasized that most men in Afghanistan love the women in their lives and treat them well. “Men in my country give women a huge amount of respect, but the only image that is left in the minds of Americans is the Taliban’s mistreatment of women,” he said. “This was a single horrible regime in our history, and most Afghans hated them.”

He told us about things I’d experienced myself in Afghanistan: women go straight to the front of lines, they are

waved past checkpoints, they’re never searched, and their cars are never stopped.

Carolyn looked at him intently. “Americans have done something very wrong to you, something you’ll never forget,” she said. “I’m asking whether it would be possible for you to try to understand that not all Americans are like the ones who have kept you here for so long.”

I don’t know whether I could have been as forgiving as Mujahid was in his reply. “I know that even every soldier here is not bad. Most have nothing to do with my arrest or lack of investigation,” he said. “I know this. And I do not hold a negative judgment of individual Americans.”

Mujahid was brought to Guantánamo Bay in mid-2003. A provincial police chief working to improve public safety, he was a strong supporter of Afghan democracy. He had welcomed U.S. soldiers to his neighborhood and maintained close contact with U.S. military officials. He had also helped orchestrate the removal of Taliban insurgents from Gardez.

When Hamid Karzai became president, Mujahid was promoted to a more senior position in Kabul. Like many others, he thought that this time peace would last in Afghanistan. He didn’t realize that he wouldn’t be a part of the new peace process. In July 2003, he was arrested in his father’s home for mysterious reasons and taken to Bagram, then eventually to Gitmo.

The murkiness surrounding his arrest has never been cleared up, and the reasons for his continued detention are

equally mysterious. The military said he had been colluding with al-Qaeda and had attacked U.S. forces in Gardez. His attorney has knocked down the allegations as hearsay one by one. But as her client was cleared of one set of accusations, the military would come up with new ones. In 2005, the Department of Defense (DOD) decided to accuse him of something fairly far-fetched. It alleged that he had played a pivotal role in a separatist group called Lashkar-i-Tayiba, which operated cells in Indian-occupied Kashmir.

The allegation seemed absurd. Mujahid had had nothing to do with the struggle between India and Pakistan over the disputed Kashmiri territory. But when Carolyn did an Internet search on Mujahid, she found that there was in fact a man named Abdullah Mujahid who was intricately tied to the Kashmiri separatist group. It just wasn’t her client. According to press reports, the Abdullah Mujahid of Lashkar-i-Tayiba died in November 2006, while her client was still at Gitmo. It was a bad case of mistaken identity, and Carolyn quickly pointed it out to the military.