Mrs. Pringle of Fairacre (9 page)

Read Mrs. Pringle of Fairacre Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Domestic Fiction, #Country Life - England, #Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place)

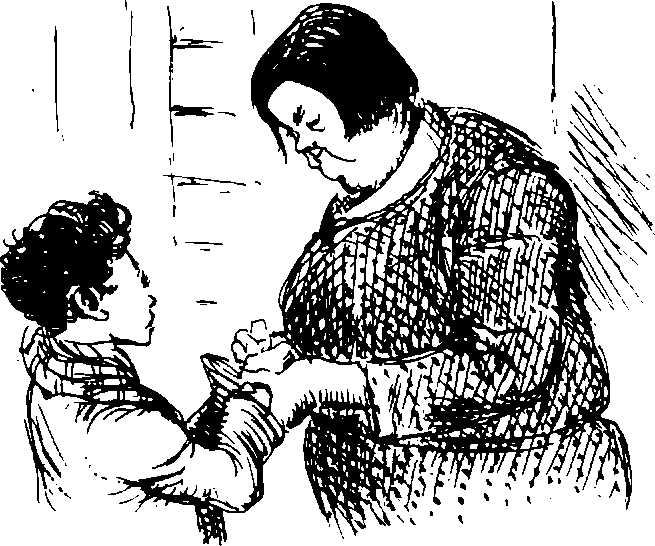

'Well, I'm blowed!' said Mrs Pringle, dignity abandoned in her shock. 'Where did you get that, Joe?'

'Mr Lamb,' faltered Joseph. 'You left it in the Post Office.'

'I've been looking all over for it,' said Mrs Pringle, 'and been worrying about where it could be. Been through my oil-cloth bag times without number, and was just going to search the street.'

She took the key from the child's hand, and felt how cold it was, as cold as the heavy key itself.

'Where's your gloves, boy?'

'Ain't got none.'

'Not at home even?'

'No.'

Mrs Pringle snorted, and Joseph felt his fear returning. Was it so wrong not to have gloves?

'Well, you're a good boy to have brought my key back. You run along home now before it gets dark, and thank you.'

The child turned without a word, cold hands thrust into the pockets of his dilapidated raincoat, and made his way homeward.

***

Later in the day when I had first seen Joe's new gloves, Mrs Pringle and I were alone in the classroom. The children had gone home and all was quiet.

I locked my desk drawers while Mrs Pringle dusted window sills and hummed 'Lead kindly light, amidst the encircling gloom', rather flat.

The key in my hand reminded me of Joseph Coggs. Curiosity prompted me to broach the subject.

'Young Joe has a splendid pair of winter gloves,' I observed.

The humming stopped, and Mrs Pringle faced me, looking disconcerted, which was a rare occurrence.

'Well, time he had! No child should be out in this weather with his hands bare.'

'No,' I agreed. She was about to resume her dusting, but I wanted to know more.

'And were you the kind soul who knitted them?'

Mrs Pringle sat heavily on a desk which creaked in protest.

'The child did me a good turn,' she said. 'I been and left the school key on Mr Lamb's counter, and he give it to Joe to bring along to me. And that child's hands!'

Here Mrs Pringle raised her own podgy ones in horror. 'Cold as clams, they was. A perishing day it was, as well I know, having to get these stoves going far too early. I don't hold with encouraging them Coggses in their slatternly ways, but there's such a thing as Christian Kindness, and seeing how young Joe had helped me out, I thought: "One good turn deserves another" and I got down to the knitting that same evening.'

'It was very good of you,' I said sincerely.

'Well, I had a bit of double-knitting over from our John's sweater, and it did just nicely. The boy seemed grateful. I slipped them to him a morning or two later, and told him to keep them out of his dad's sight.'

'Surely he wouldn't take those?'

'Arthur Coggs,' said Mrs Pringle, 'would drink the coat off your back, if you gave him a chance. And now, if I don't get this dusting done I shan't be back in time to get Pringle's tea.'

Thus dismissed, I left her to her cleaning. She was still humming as I closed the door - it sounded like 'Abide with me', rather sharp.

Whether it was the inescapable draught from the skylight, the wintry weather, or simply what the medical profession calls 'a virus' these days, the result was the same. I went down with an appalling cold.

It was one of those which cannot be ignored. For

several days I had been at the tickly throat stage with an occasional polite blow into a handkerchief, but one night, soon after my conversation with Mrs Pringle, all the germs rose up in a body and attacked me.

By morning every joint ached, eyes streamed, head throbbed and I was too cowardly to take my temperature. It was quite clear that I should be unable to go over to the school, for as well as being highly infectious and pretty useless, I was what Mr Willet described once as 'giddy as a whelk'.

I scribbled a note to Miss Clare, and dropped it from my bedroom window to the first responsible child to appear in the playground.

At twenty to nine, my gallant assistant appeared at the bedroom door.

'Don't come any nearer,' I croaked. 'I'm absolutely leprous. I'm so sorry about this. As soon as it is nine o'clock I'll ring the Office and see if we can get a supply teacher for a couple of days.'

'I shall ring the Office,' said Miss Clare, with great authority, 'and I shall bring you a cup of tea and some aspirins, and see that Doctor Martin calls.'

I was too weak to argue and accepted her help gratefully.

After my cup of tea I must have fallen asleep, for the next I knew was the sound of Doctor Martin's voice as he came upstairs. As always, he was cheerful, practical and brooked no argument.

'When did this start?' he asked when he had put the thermometer into my mouth.

I wondered, not for the first time, why doctors and dentists ask questions when you are effectively gagged by the tools of their trade.

'About two or three days ago,' I replied, when released from the thermometer.

'You should have called me then,' he said severely. How is it, I wondered, that doctors can so quickly put you in the wrong?

Relenting, he patted my shoulder. 'You'll do. I'll just write you a prescription and you are to stay in bed until I come again.'

'And when will that be?' I asked, much alarmed.

'The day after tomorrow. But I shan't let you loose until that temperature's gone down.'

He collected his bits and pieces, gave me a beaming smile, and vanished.

I resumed my interrupted slumbers.

It was getting dark when I awoke, and I could hear the children running across the playground on their way home. I could also hear movements downstairs, and wondered if Miss Clare had come over again on a mission of mercy, but to my surprise, it was Amy who appeared, bearing a tea tray.

I struggled up, wheezing a welcome.

'Dolly Clare rang me,' she said, 'and as James is in Budapest, or it may be Bucharest, I was delighted to come. What's more, I've collected your prescription, and pretty dire it looks and smells.'

She deposited a bottle of dark brown liquid on the bedside table.

'I may not need it,' I said, 'after a good cup of tea.'

'You'll do as you're told,' replied Amy firmly, 'and take your nice medicine as Doctor Martin said.'

We sipped our tea in amicable silence, and then Amy told me that she intended to stay until the doctor called again.

'But what about the school? I can't leave Miss Clare to cope alone.'

'Someone's coming out tomorrow, I gather, and in any case, I could do a hand's turn.

I am a

trained teacher, if you remember, and did rather better than you did in our final grades.'

She vanished to make up the spare bed, and left me to my muddled thoughts for some time. I thought I heard her talking outside in the playground, but decided it must be Miss Clare or even Mrs Pringle going about their affairs.

When Amy reappeared, the clock said half past seven.

'I can't think what's happened to today,' I complained, 'I must keep falling asleep.'

'You do,' she assured me, 'and a good thing too.'

'But there's such a lot to do. The kitchen's in a fine mess. I left yesterday's washing up, and the grate hasn't been cleared.'

'Oh yes, it has! Mrs Pringle came over after she'd finished at the school. She had it all spick and span in half an hour.'

'Amy,' I squeaked, 'you haven't asked

Mrs Pringle

to help! You know how I've resisted all this time.'

'And what's more,' went on Amy imperturbably, 'she is quite willing to come every Wednesday afternoon, if you need her.'

'Traitor!' I said, but I was secretly amused and relieved.

'Time for medicine,' replied Amy, advancing on the bottle.

Christmas

As so often happens in the wake of nervous apprehension, reality proved less severe than my fears.

The advent of Mrs Pringle into my personal affairs had its advantages. For one thing, the house benefitted immediately from her ministrations. Furniture gleamed like satin, windows were crystal clear, copper and brass objects were dazzling, and even door knobs on cupboards, which had never hitherto seen a spot of Brasso, were transformed.

The beauty of it was, from my point of view, that I hardly came across the lady when she was at her labours. She chose to come on a Wednesday afternoon. (Mrs Hope, that paragon of domestic virtue who had been an earlier occupant in the school house, had always preferred Wednesdays, according to Mrs Pringle.) So Wednesday it was.

She went straight from her washing up in the school lobby to my house, and worked from half past one until four o'clock. As I was teaching then it meant that I seldom saw her in the house, but simply marvelled at the shining surfaces when I returned.

Occasionally, of course, I ran into her and we would share a pot of tea before she set off for home.

It was on one of these tea-drinking sessions that she first told me about her niece, Minnie Pringle, daughter of the black sheep of the family, Josh Pringle of Springbourne.

'She come up this morning to see if I'd got any jumble for their W.I. sale next week. At least, that's what

she said

she'd come for, but it was money she was after for herself.'

I knew that the girl had two small children, so enquired innocently if her husband was out of work.

'Work?

A

husband

?' cried Mrs Pringle. 'Minnie never had a husband. These two brats of hers is nothing more than you-know-what beginning with a B but I wouldn't soil my lips with saying it.'

'Oh dear,' I said feebly. 'I didn't realise...'

'And another on the way, as far as I could see this morning. One is one thing, most people give a girl the benefit of the doubt. But two is taking things too far, especially when the silly girl can't say for sure who the father is.'

'She must have

some

idea.'

'Not Minnie, she's that feckless she just wouldn't remember. Not that she's entirely to blame. That father of hers, our Josh - though I'm ashamed to claim him as part of the Pringle family - he's an out and out waster, and his poor wife is as weak-minded as our Minnie. Nothing but a useless drudge, and never gave Minnie any idea of Right and Wrong.'

'But surely -' I began, but was swept aside by Mrs Pringle's rhetoric. Mrs P. in full spate is unstoppable.

'I told her once, "If you can't tell that girl of yours the facts of life, then send her to church regular. She'll soon find out all about adultery."'

It seemed a somewhat narrow approach to the church's teachings but I did not have the strength to argue.

'More tea?' I asked.

Mrs Pringle raised a massive hand, rather as if she were holding up the traffic. 'Thank you, no. I'm awash. Must get along to fetch my washing in. It looks as though there's rain to come.'

I accompanied her to the gate. A few children were still in the playground taking their time to go home.

'Mind you,' said Mrs Pringle, dropping her voice to a conspiratorial whisper in deference, I presumed, to the innocent ears so near us, 'if there

is

another on the way, I shan't put myself out with more baby knitting. Minnie don't have any idea how to wash knitted things. It's my belief she

boils them

!'

As Christmas approached that term, the school began to deck itself ready for the festival.

In the infants' room a Christmas frieze running around the walls kept Miss Briggs's children busy. Santa Claus, decked in plenty of cotton wool, Christmas trees, reindeer resembling rabbits, otters, large dogs and other denizens of the animal world, as well as sacks of toys, Christmas puddings, Christmas stockings and various other domestic signs of celebration were put in place by the young teacher's careful hands, and glitter was sprayed plentifully at strategic points.

At least, the stuff was supposed to be at strategic points such as the branches of the Christmas trees, but glitter being what it is we found it everywhere. It appeared on the floor, on the window sills, in the cracks of desks, and sometimes a gleam would catch our eyes in the school dinner, blown there, no doubt, by the draught from the door. The stoves suffered too, much to Mrs Pringle's disgust.

In my own room, glitter was banned on the grounds

that we had quite enough from the room next door, but we had a large picture of a Christmas tree, on which the children stuck their own bright paintings. We also made dozens of Christmas cards for home consumption, and some rather tricky boxes to hold sweets.

I bought the sweets, a nice straightforward approach to Christmas jollifications. The construction of the boxes, which appeared such a simple operation from the diagram in

The Teachers' World,

was not so easy. Half the boxes burst open at the seams whilst being stuck together. The rest looked decidedly drunken. By the time we had substituted a household glue for the paste we had so hopefully mixed up, the place reeked with an unpleasant fishy smell and I was apprehensive about the sweets although they were wrapped.

However, nothing could quell the high spirits of the children, and the traditional Christmas party for their parents and friends of the school was its usual jubilant occasion on the last afternoon.