Mrs. Pringle of Fairacre

Read Mrs. Pringle of Fairacre Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Domestic Fiction, #Country Life - England, #Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place)

Miss Read

Illustrated by J. S. Goodall

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston New York

First Houghton Mifflin paperback edition 2001

Copyright © 1989 by Miss Read

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Visit our Web site:

www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Read, Miss.

Mrs. Pringle of Fairacre

ISBN 0-618-155 88-0 (pbk)

I. Title.

PR

6069.

A

42

M

58 1990

B

823'. 914âdc20 90-4669

Printed in the United States of America

QUM

10 9 8

To Vicki and Horace

with love

Face to Face

It is snowing again. We shall certainly have a white Christmas this year, a rare occurrence even in this downland village of Fairacre.

I have been the head teacher of Fairacre School for more years than I care to remember, and the school house, where I write this, has been my home for all that time. It is particularly snug at the moment: the fire blazes, the cat is stretched out in front of it, and Christmas cards line the mantelpiece. Very soon the school breaks up for the Christmas holidays, and what a comforting thought that is!

Comfort is needed, not only from the snowflakes which whisper at the window, but also from the aftermath of a recent skirmish with Mrs Pringle, our school cleaner, who has lived in the village even longer than I have.

She does her job superbly, but is a sore trial. It is generally agreed that she is 'difficult', the vicar's expression, and 'a proper Tartar', as Bob Willet our handyman and school caretaker puts it.

During term time our paths cross on most days. It is no wonder that I relish the school holidays and the peace that they bring. How long, I muse, putting another log on the

fire, will I be able to stand her aggression? Stroking Tibby's warm stomach, I look back through the years at my tempestuous relationship at Fairacre School with the doughty Mrs Pringle.

I first encountered Mrs Pringle one thundery July afternoon.

It was a Friday, I remember. The vicar, the Reverend Gerald Partridge who was chairman of the school governors, had invited me to tea before looking over the school house which was to become my home at the end of the month. I had recently been appointed head mistress of Fairacre School.

There were puddles in the playground, and we splashed through them on our way to the school house. A strange mooing noise, as of a cow or calf in distress, was coming from the deserted school building. The children of Fairacre had already started their summer holiday.

'That,' said Mr Partridge, 'is Mrs Pringle, our school cleaner. It sounds as though she is singing a hymn. She is in the church choir.'

We paused for a moment, listening to the distant voice and the plop of raindrops into puddles.

'I don't recognise it,' I ventured.

'Probably the descant,' replied the vicar. He did not sound very sure. 'In any case, perhaps I should take you to meet her before we visit the house.'

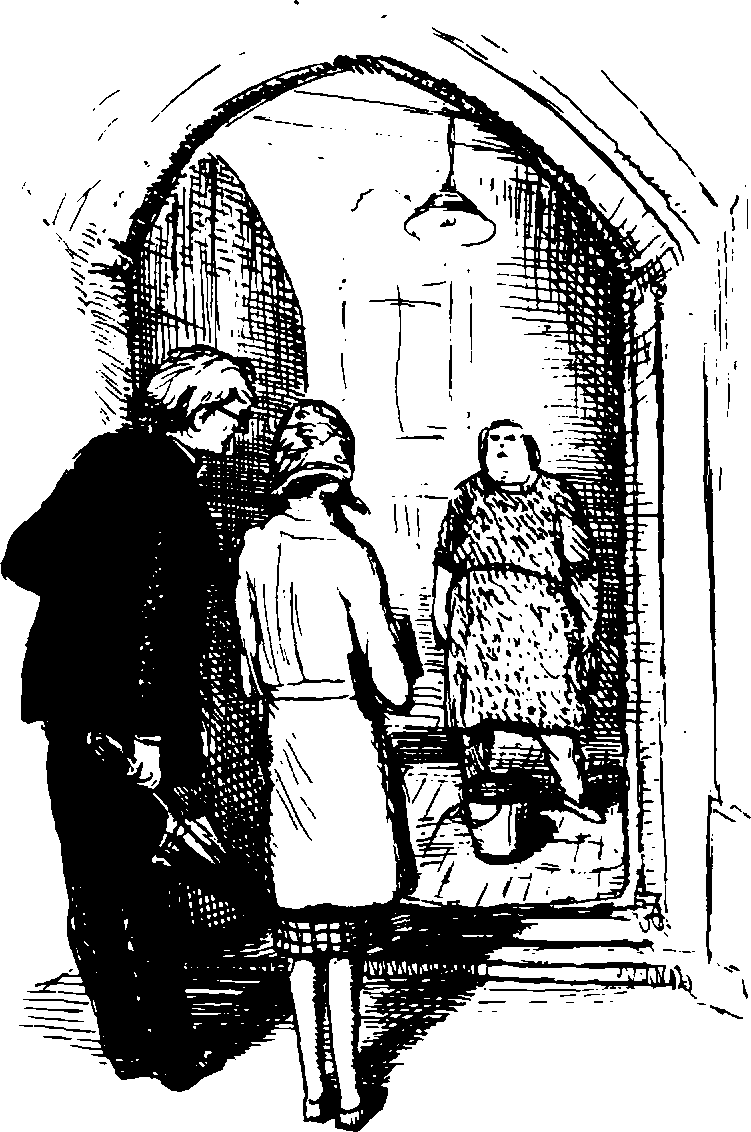

We changed direction, and the vicar pushed open the door into the lobby.

Mrs Pringle, bucket at her feet and floor cloth in the other, stood before us. She was short and stout. Her expression was dour. She made no attempt to smile, offer a hand, or make any other gesture of welcome as the vicar introduced us.

Eventually, she jerked her head towards the floor where our feet had made wet prints.

'I just done that,' she remarked, the four words dropping as cold and flat as the stones upon which we stood.

Although I did not know it at the time, it was the first shot in a war which was to last for many years.

I was the first woman to be appointed head teacher of Fairacre School, and I looked forward eagerly to taking up my duties.

The downland village and the market town of Caxley were known to me, for my good friend Amy who had been with me at college, had married and lived south of Caxley in the village of Bent. On my frequent weekend visits we explored the countryside, and often drove up to the downs for a picnic and an exhilarating walk. We drove through the villages of Beech Green and Fairacre and sometimes stopped to look round their churches, or to buy something from Beech Green's village shop.

When I had seen the headship of Fairacre School advertised in

The Times Educational Supplement

I had applied for the post.

'I'm not likely to get it,' I said to Amy, 'I doubt if I shall even get called to an interview.'

'Rubbish!' said Amy stoutly. 'You are better qualified than most, and I'm positive you'll get the job.'

Although I was grateful for this display of support, biased though it was, I had private misgivings. Consequently, when I was appointed, I felt both pride and trepidation. Could I fulfil the governors' hopes, and would the children and parents be co-operative?

I need not have worried.

Any initial suspicions or doubts on the part of the

inhabitants of Fairacre were soon hidden from me, and as the years passed I was accepted as part of the village community. I could never expect to be in the same category as a native, born and bred in Fairacre, but to be welcomed was quite enough for me.

But on that humid thundery afternoon I was still at the apprehensive stage, and my encounter with the school cleaner aroused my fears.

I tried to put them aside as I followed the vicar round my new home. It was a snug well-built house with a good-sized sitting room, and a decent kitchen flanked by a small dining room. Upstairs were two bedrooms and a tiny box room, later destined to be a bathroom.

At that time the house was empty, for my predecessor, Mr Fortescue, had moved out just before his retirement. It

was Mrs Pringle, the vicar told me, who had a key and kept the premises clean.

'In fact,' went on the vicar, 'she has cared for this house for many years.'

'I see,' I said, my heart sinking.

'Of course, it is entirely up to you, but if you felt like continuing to employ her, I am sure she would carry on.'

'Thank you for telling me.'

'She is really a wonderful worker,' persisted the vicar as we went out into the dripping garden. 'Her manner is a little off-putting, I know, but she is diligent and honest, and has always taken a great pride in her work.'

I did not reply, determined not to commit myself at this stage, to being hostess to Mrs Pringle for years to come.

'What a lovely garden!' I said, changing the subject.

There were a few mature fruit trees displaying small unripe apples, plums and pears, and an impressive herbaceous border flaunting lupins, delphiniums and oriental poppies.

The flowers were looking rather battered from the recent rain, the border was undoubtedly weedy and the lawn shaggy, but basically it was a splendid garden, and my spirits rose.

'Yes, Mr Willet gives a hand,' said the vicar. 'In fact, he gives a hand at most of our activities, as you will find.'

He drew out a watch from his waistcoat pocket.

'Dear, dear! I think we should get back to the vicarage. My wife will have tea ready.'

We retraced our steps to rejoin Mrs Partridge and Amy who had brought me over, and who had spent the time, I learned later, in unravelling the sleeve of a cardigan which the vicar's wife was engaged upon. She had misread the directions for increasing, and the sleeve was ballooning out

in an alarming fashion, to say nothing of using up all the wool before the whole thing was finished.

As the vicar and I walked up the drive to our tea he returned to the subject of Mrs Pringle.

'Do consider the matter of employing her,' he urged. 'I feel sure she is expecting it.'

He sounded, I thought, somewhat nervous. Was he

frightened

of the lady, I wondered? Was she really as fearsome as she undoubtedly looked? It only strengthened my determination not to commit myself.

'I'll certainly consider it,' I assured him, as he opened the front door.

'Ah, good!' he replied, sounding much relieved. 'And good again, I think I can smell toasted teacakes.'

On the way back to Bent, I prattled happily to Amy about the school house and garden, and how much I looked forward to living there.

'You must let me give you a hand in getting it ready,' said Amy, hooting at a pheasant who strolled haughtily across the road intent on suicide.

'I should enjoy your company,' I replied.

'It's not so much my

company,

' said Amy severely, 'as my

advice

you will need. You know you've never been much good at measuring accurately, and I haven't much opinion of your sense of colour.'

'Thank you,' I said, trying not to sound nettled. That is the worst of friends who have known you from youth. They remember all those faults which one has done one's best to eradicate over the years. However, Amy always means well, despite her undoubted bossiness, and on this occasion I managed not to answer back.

In any case, I reminded myself, I had quite a few

memories of Amy's early indiscretions, and should have no hesitation in using them if she continued to rake up the infirmities in my own past.

But I was too euphoric about my future to take serious offence as Amy's car swished through the puddles. The sky remained lowering, and it was obvious that the thunderstorm was not yet over.

'Of course, the garden needs tidying,' I continued, 'but the vicar seems to think that someone called Bob Willet will give a hand. I must get in touch with him.'

'And what about the house?'

I felt a slight pang as I recalled Mrs Pringle's visage, quite as dark and menacing as the sky overhead.

'Well,' I began, 'the school cleaner seems to have looked after the head teacher's house before, but I didn't really take to her.'

'Taking to her or not,' said Amy, 'is beside the point. You're not exactly the model housewife, as you well know. I should advise you to take whatever domestic help is offered.'

'But, Amy,' I protested, 'you haven't seen this Mrs Pringle. She's quite formidable. Why, I believe the vicar himself is afraid of her, and after all he's girt about with righteousness and all the other Christian armament. What hope for a defenceless woman like me?'

'You exaggerate,' replied Amy, swinging neatly into her drive. 'I'll come over with you next time and meet the lady.'

And what a clash of the dinosaurs that could be, I thought with some relish as I clambered from the car.

James, Amy's husband, proved to be a welcome ally later that evening when the subject of help in my new abode cropped up.

'I shouldn't saddle myself with that lady if I were you,' he said. 'Fob her off. Say you want to see how things work out. Play for time.'

'My feelings entirely,' I responded. 'I didn't like to press Mr Partridge too much. He seems so anxious not to offend her, but perhaps a few discreet enquiries among other villagers would be useful. This Bob Willet might be helpful.'