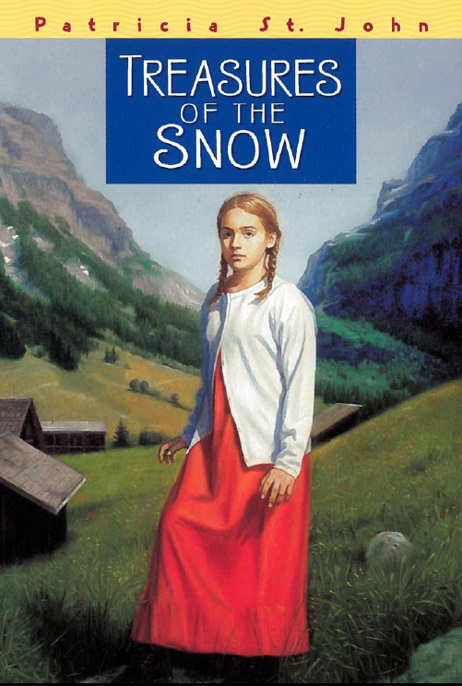

Treasures of the Snow

Read Treasures of the Snow Online

Authors: Patricia St John

Treasures of the Snow

Patricia St John

Revised by Mary Mills

Illustrated by Gary Rees

M

OODY

P

UBLISHERS

CHICAGO

© 1948 P

ATRICIA

M. S

T

. J

OHN

First published 1948

This edition first published 1999

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

Interior and Cover Design: Ragont Design

Cover Illustration: Matthew Archambault

ISBN: 0-8024-6575-7

ISBN-13: 978-0-8024-6575-7

Printed by Versa Press in Peoria, IL – 04/2010

We hope you enjoy this book from Moody Publishers. Our goal is to provide high-quality, thought-provoking books and products that connect truth to your real needs and challenges. For more information on other books and products written and produced from a biblical perspective, go to

www.moodypublishers.com

or write to:

Moody Publishers

820 N. LaSalle Boulevard

Chicago, IL 60610

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

3 A Very Special Christmas Present

11 A Trip to the High Pastures

15 Christmas Again—and Gingerbread Bears

22 Lucien Finds Monsieur Givet

24 Jesus’ Love Makes All the Difference

Revised Edition

It has been over fifty years since the first editions of Patricia St. John’s

Treasures of the Snow

and

The Tanglewoods’ Secret

were published, and they have become classics of their time.

In these new editions, Mary Mills has sensitively adapted the language of the books for a new generation of children, while preserving Patricia St. John’s superb skill as a storyteller.

A note from the author

W

hen I was a child of seven I went to live in Switzerland. My home was a chalet on the mountain, above the village where I have imagined Annette and Dani to live.

Like them, I went to the village school on a sled by moonlight, and helped to make hay in summer. I followed the cows up the mountain, and slept in the hay. I went to church on Christmas Eve to see the tree covered with oranges and gingerbread bears, and was taken to visit the doctor in the town up the valley. Klaus was my own white kitten, given to me by a farmer, and my baby brothers rode in the milk cart behind the great St. Bernard dog.

But all this was over twenty years ago, and I have been back only as a visitor; Switzerland today is probably very different. I expect it would be impossible now for a child to miss school for any length of time, and no doubt the medical service has improved. Perhaps all little villages have their own doctors now. I do not know.

But I do know that today, as twenty years ago, the little school and the church still stand, the cowbells still tinkle in the valley, and the narcissi still scent the fields in May. And I hope that little children still sing carols under the tree at Christmas and love their gingerbread bears as much as I loved mine.

I have not given the village its proper name, because for the sake of the story, I have added one or two things that are not really there. For instance, there is no town nearby that could not be reached except by the Pass. But otherwise I have tried to keep it true to life, and if ever you go to Switzerland and take an electric train up from Montreux you will stop at a tiny station where hayfields bound the platform and high green hills rise up behind, dotted with chalets. To the right of the railway the banks drop down into a foaming, rushing river, beyond which the mountains rise again, and between a long, green mountain and a rocky, pointed mountain there lies a Pass. If, added to all this, you see a low white school building not far from the station and a wooden church spire rising from behind a hillock, you will know that this is the village where this story was born.

Patricia St. John

1950

Christmas Eve

I

t was Christmas Eve, and three people were climbing the steep, white mountainside, the moonlight throwing shadows behind them across the snow. The middle one was a woman in a long skirt with a dark cloak over her shoulders. Clinging to her hand was a black-haired boy of six, who talked all the time with his mouth full. Walking a little way away from them, with her eyes turned to the stars, was a girl of seven. Her hands were folded across her chest, and close to her heart she carried a golden gingerbread bear with eyes made of white icing.

The little boy had also had a gingerbread bear, but he had eaten it all except the back legs. He looked at the girl spitefully. “Mine was bigger than yours,” he said.

The girl did not seem upset. “I would not change it,” she replied calmly, without turning her head. Then she looked down again with eyes full of love at the beautiful bear in her arms. How solid he looked, how delicious he smelled, and how brightly he gleamed in the starlight. She would never eat him, never!

Eighty little village children had been given gingerbread bears, but hers had surely been by far the most beautiful.

Yes, she would keep him forever in memory of tonight, and whenever she looked at him she would remember Christmas Eve—the frosty blue sky, the warm glow of the lighted church, the tree decorated with silver stars, the carols, the crib, and the sweet, sad story of Christmas. It made her want to cry when she thought about the inn where there was no room. She would have opened her door wide and welcomed Mary and Joseph in.

Lucien, the boy, was annoyed by her silence. “I have nearly finished mine,” he remarked, scowling. “Let me taste yours, Annette. You have not started it.” But Annette shook her head and held her bear a little closer. “I am never going to eat him,” she replied. “I am going to keep him forever and ever.”

They had come to where the crumbly white path divided. A few hundred yards along the right fork stood a group of chalets with lights shining in their windows and dark barns standing behind them. Annette was nearly home.

Madame Morel hesitated. “Are you all right to run home alone, Annette?” she asked doubtfully, “or shall we take you to the door?”

“Oh, I would much rather go home alone,” answered Annette, “and thank you for taking me. Good night, Madame; good night, Lucien.”

She turned and ran, in case Madame should change her mind and insist on seeing her to the door. She so badly wanted to be alone.

She wanted to get away from Lucien’s chatter and enjoy the silence of the night. How could she think, and look at the stars, when she was having to make polite replies to Madame Morel and Lucien?

She had never been out alone at night before, and even this was a sort of accident. She was supposed to have gone to the church on the sleigh with her parents. They had all been thinking about it and planning it for weeks. But that morning her mother had been taken ill and her father had gone off on the midday train to fetch the doctor from the town up the valley. The doctor had arrived about teatime, but he could not cure her in time to get up and go to church as Annette had hoped he would, so to her great disappointment she had to go instead with Madame Morel from the chalet up the hill. But when she had reached the church it had been so beautiful that she had forgotten everything but the tree and the magic of Christmas, so it had not mattered so much after all.

The magic stayed with her, and now, as she stood alone among snow and stars, it seemed a pity to go in just yet and break the spell. She hesitated as she reached the steps leading up to the balcony and looked around. Just opposite loomed the cowshed; Annette could hear the beasts moving and munching from the manger.

An exciting idea struck her. She made up her mind in a moment, darted across the sleigh tracks, and lifted the latch of the door. The warm smell of cattle and milk and hay greeted her as she slipped inside. She wriggled against the legs of the chestnut-colored cow and wormed her way into the hayrack. The cow was having supper, but Annette flung her arms around its neck and let it go on munching, just as the cows must have munched when Mary sat among them with her newborn baby in her arms.

She looked down at the manger and imagined Baby Jesus was lying in the straw with the cows, still and quiet, worshipping about Him. Through a hole in the roof she could see one bright star, and she remembered how a star had shone over Bethlehem and guided the wise men to the house where Jesus lay. She could imagine them padding up the valley on their swaying camels. And surely any moment now the door would open softly and the shepherds would come creeping in with little lambs in their arms and offer to cover the child with woolly fleeces. As she leaned further, a great feeling of pity came over her for the homeless baby who had had all the doors shut against him.

“There would have been plenty of room in our chalet,” she whispered, “and yet perhaps after all this is the nicest place. The hay is sweet and clean and Louise’s breath is warm and pleasant. Maybe God chose the best cradle for his baby after all.”

She might have stayed there dreaming all night if it had not been for the gleam of a lantern through the half-open door of the shed and the sound of firm, crunchy footsteps in the snow.

Then she heard her father call her in a quick, hurried voice.

She slipped down from the rack, dodged Louise’s tail, and ran out to him with wide-open arms.

“I went in to wish the cows a happy Christmas,” she said, laughing. “Did you come out to find me?”

“Yes, I did,” he replied, but he was not laughing. His face was pale and serious in the moonlight, and he took her hand and almost dragged her up the steps. “You should have come in at once, with your mother so ill. She has been asking for you for half an hour.”

Annette suddenly felt very sorry, for somehow the Christmas tree had made her forget about everything else, and all the time her mother, whom she loved so much, was lying ill and wanting her. She had thought the doctor would have made her better. She took her hand out from her father’s and ran up the wooden stairs and into her mother’s bedroom.

Neither the doctor nor the village nurse saw her until she had crept up to the bed, for she was a small, slim child who moved almost silently. But her mother saw her and half held out her arms. Annette, without a word, ran into them and hid her face on her mother’s shoulder. She began to cry quietly, for her mother’s face was almost as white as the pillow and it frightened her. Besides, she felt sorry for having been away so long.