More Guns Less Crime (8 page)

Read More Guns Less Crime Online

Authors: John R. Lott Jr

Tags: #gun control; second amendment; guns; crime; violence

General population, 1988 General population, 1996

Gun ownership by size of community and by age

Figure 3.4. Percent of people living in different-size communities and in different age groups who owned guns in 1988 and 1996

states, and over 770 respondents for three other states. The 1996 survey was less extensive, with only fourteen of the states surveyed having at least 100 respondents. Since these fourteen states were relatively more urban, they tended to have lower gun-ownership rates than the nation as a whole.

The polls show that the increase in gun ownership was nationwide and not limited to any particular group. Of the fourteen states with enough respondents to make state-level comparisons, thirteen states had more people owning guns at the end of this period. Six states each had over a million more people owning guns. Only Massachusetts saw a decline in gun ownership.

States differ significantly in the percentage of people who own guns. On the lower end in 1988, in states like New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, only 10 or 11 percent of the population owned guns. Despite its reputation, Texas no longer ranks first in gun ownership; California currently takes that title—approximately 10 million of its citizens own guns. In fact, the percentage of people who own guns in Texas is now below the national average.

Understanding Different Gun Laws and Crime Rate Data

While murder rates have exhibited no clear trend over the last twenty years, they are currently 60 percent higher than in 1965. 9 Driven by sub-

Table 3.1 Gun-ownership rates by state

CBS General Election Exit Poll (November 8, 1988) surveyed 34,245 people

Voter News Service General Election

Exit Poll (November 5, 1996) surveyed

3,818 people

Change in states over time

Table 3.1 Continued

CBS General Election Exit Poll (November 8, 1988) surveyed 34,245 people

Voter News Service General Election

Exit Poll (November 5, 1996) surveyed

3,818 people

Change in states over time

Source: The polls used are the General Election Exit Polls from CBS (1988) and Voter News Service (1996). The estimated percent of the voting population owning a gun is obtained by using the weighting of responses supplied by the polling organizations. The estimated percent of the general population owning a gun uses a weight that I constructed from the census to account for the difference between the percentage of males and females; whites, blacks, Hispanics and others; and these groups by age categories that are in the voting population relative to the actual state-level populations recorded by the census. 'State poll numbers based upon at least 770 respondents per state.

2 State poll numbers based upon at least one hundred respondents per state. Other states were surveyed, but the number of respondents in each state was too small to provide an accurate measure of gun ownership. These responses were still useful in determining the national ownership rate, even if they were not sufficient to help determine the rate in an individual state.

GUN OWNERSHIP, GUN LAWS, DATA ON CRIME/43

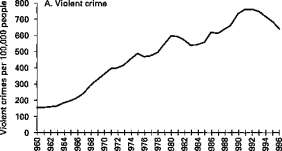

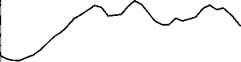

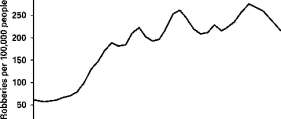

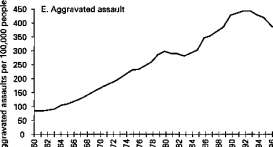

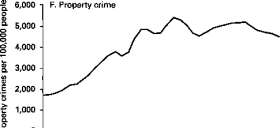

stantial increases in rapes, robberies, and aggravated assaults, violent crime was 46 percent higher in 1995 than in 1976 and 240 percent higher than in 1965. As shown in figure 3.5, violent-crime rates peaked in 1991, but they are still substantially above the rates in previous decades.

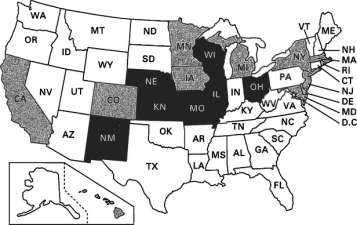

Such high violent-crime rates make people quite concerned about crime, and even the recent declines have not allayed their fears. Stories of people who have used guns to defend themselves have helped motivate thirty-one states to adopt nondiscretionary (also referred to as "shall-issue" or "do-issue") concealed-handgun laws, which require law-enforcement officials or a licensing agency to issue, without subjective discretion, concealed-weapons permits to all qualified applicants (see figure 3.6). This constitutes a dramatic increase from the eight states that had enacted nondiscretionary concealed-weapons laws prior to 1985. The requirements that must be met vary by state, and generally include the following: lack of a significant criminal record, an age restriction of either 18 or 21, various fees, training, and a lack of significant mental illness. The first three requirements, regarding criminal record, age, and payment of a fee, are the most common. Two states, Vermont and Idaho (with the exception of Boise), do not require permits, though the laws against convicted felons carrying guns still apply. In contrast, discretionary laws allow local law-enforcement officials or judges to make case-by-case decisions about whether to grant permits, based on the applicant's ability to prove a "compelling need."

When the data set used in this book was originally put together, county-level crime data was available for the period between 1977 and 1992. During that time, ten states—Florida (1987), Georgia (1989), Idaho (1990), Maine (1985), 10 Mississippi (1990), Montana (1991), Oregon (1990), Pennsylvania (1989), Virginia (1988), 11 and West Virginia (1989)—adopted nondiscretionary right-to-carry firearm laws. Pennsylvania is a special case because Philadelphia was exempted from the state law during the sample period, though people with permits from the surrounding Pennsylvania counties were allowed to carry concealed handguns into the city. Eight other states (Alabama, Connecticut, Indiana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Washington) have had right-to-carry laws on the books for decades. 12

Keeping in mind all the endogeneity problems discussed earlier, I have provided in table 3.2 a first and very superficial look at the data for the most recent available year (1992) by showing how crime rates varied with the type of concealed-handgun law. According to the data presented in the table, violent-crime rates were highest in states with the most restrictive rules, next highest in the states that allowed local authorities discretion in granting permits, and lowest in states with nondiscretionary rules.

A. Violent crime

OiOiOiOiOiOiOiOi

Year

12 t B. Murder

10

Q. O © Q.

O

£ 6 -

a

J2 a

"2

=3 2

2 -

0 I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

ON^(000ON^(000ON^(000O(M^(0 <0<0<0<0

0>0>0>O>O>0>0)O)O)O)

Year

45 -I C. Rape

40 -

Q.

O

Q.

to

CC

35 30 25 20 15 10 -5 -

0 I I I l I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

SM^tDOOON^tDOOOM'ttDOOOM^lO (O(O(53NNhhh0000l»00SSO)O>O)(» 0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)0)

Year

Figure 3.5. U.S. crime rates from 1960—1996 (from FBI's Uniform Crime Reports)

300 -I D. Robbery

0 I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I 1 I I I I II I I I I I I I

_)OQOCW'

CM _ CD

a> o)

Year

_cococDCDr-r-r-r-r-oooooooo —

OiOiOiOiOiOiOiOiOiOiOiOiOiOiOi

Year

Year

Figure 3.5. Continued

I I States with nondiscretionary rules or no permit requirements || States with discretionary rules | States forbidding concealed handguns