More Guns Less Crime (7 page)

Read More Guns Less Crime Online

Authors: John R. Lott Jr

Tags: #gun control; second amendment; guns; crime; violence

Another concern is that otherwise law-abiding citizens may have carried concealed handguns even before it was legal to do so. 22 If nondiscre-tionary laws do not alter the total number of concealed handguns carried by otherwise law-abiding citizens, but merely legalize their previous actions, passing these laws seems unlikely to affect crime rates. The only real effect from making concealed handguns legal could arise from people being more willing to use them to defend themselves, though this might also imply that they would be more likely to make mistakes in using them.

It is also possible that concealed-firearm laws both make individuals safer and increase crime rates at the same time. As Sam Peltzman has pointed out in the context of automobile safety regulations, increasing safety may lead drivers to offset these gains by taking more risks as they

34/CHAPTER TWO

drive. 23 Indeed, recent studies indicate that drivers in cars equipped with air bags drive more recklessly and get into accidents at sufficiently higher rates to offset the life-saving effect of air bags for the driver and actually increase the total risk of death for others. 24 The same thing is possible with regard to crime. For example, allowing citizens to carry concealed firearms may encourage them to risk entering more dangerous neighborhoods or to begin traveling during times they previously avoided:

Martha Hayden, a Dallas saleswoman, said the right-to-carry law introduced in Texas this year has turned her life around.

She was pistol-whipped by a thief outside her home in 1993, suffering 300 stitches to the head, and said she was "terrified" of even taking out the garbage after the attack.

But now she packs a .357 Smith and Wesson. "It gives me a sense of security; it allows you to get on with your life," she said. 25

Staying inside her house may have reduced Ms. Hayden's probability of being assaulted again, but since her decision to engage in these riskier activities is a voluntary one, she at least believes that this is an acceptable risk. Likewise, society as a whole might be better off even if crime rates were to rise as a result of concealed-handgun laws.

Finally, we must also address the issues of why certain states adopted concealed-handgun laws and whether higher offense rates result in lower arrest rates. To the extent that states adopted the laws because crime was rising, econometric estimates that fail to account for this relationship will underpredict the drop in crime and perhaps improperly blame some of the higher crime rates on the new police who were hired to help solve the problem. To explain this problem differently, crime rates may have risen even though concealed-handgun laws were passed, but the rates might have risen even higher if the laws had not been passed. Likewise, if the laws were adopted when crime rates were falling, the bias would be in the opposite direction. None of the previous gun-control studies deal with this type of potential bias. 26

The basic problem is one of causation. Does the change in the laws alter the crime rate, or does the change in the crime rate alter the law? Do higher crime rates lower the arrest rate or the reverse? Does the arrest rate really drive the changes in crime rates, or are any errors in measuring crime rates driving the relationship between crime and arrest rates? Fortunately, we can deal with these potential biases by using well-known techniques that let us see what relationships, if any still exist after we try to explain the arrest rates and the adoption of these laws. For example, in examining arrest rates, we can see how they change due to such things as changes in crime rates and then see to what extent the unexplained

HOW TO TEST THE EFFECTS OF GUN CONTROL/35

portion of the arrest rates helps to explain the crime rate. We will find that accounting for these concerns actually strengthens the general findings that I will show initially. My general approach, however, is to examine first how concealed-handgun laws and crime rates, as well as arrest rates and crime rates, tend to move in comparison to one another before we try to deal with more complicated relationships.

Three. Gun Ownership, Gun Laws,

and the Data on Crime

Who Owns Guns?

Before studying what determines the crime rate, I would like to take a look at what types of people own guns and how this has been changing over time. Information on gun-ownership rates is difficult to obtain, and the only way to overcome this problem is to rely on surveys. The largest, most extensive polls are the exit polls conducted during the general elections every two years. Recent presidential election polls for 1988 and 1996 contained a question on whether a person owned a gun, as well as information on the person's age, sex, race, income, place of residence, and political views. The available 1992 survey data did not include a question on gun ownership. Using the individual respondent data in the 1988 CBS News General Election Exit Poll and the 1996 Voter News Service National General Election Exit Poll, we can construct a very detailed description of the types of people who own guns. The Voter News Service poll collected data for a consortium of national news bureaus (CNN, CBS, ABC, NBC, Fox, and AP).

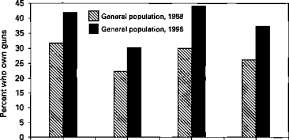

What stands out immediately when these polls are compared is the large increase in the number of people who identify themselves as gun owners (see figure 3.1). In 1988, 27.4 percent of voters owned guns. 1 By 1996, the number of voters owning guns had risen to 37 percent. In general, the percentages of voters and the general population who appear to own guns are extremely similar; among the general population, gun ownership rose from 26 to 39 percent, 2 which represented 76 million adults in 1996. Perhaps in retrospect, given all the news media discussions about high crime rates in the last couple of decades, this increase is not very surprising. Just as spending on private security has grown dramatically—reaching $82 billion in 1996, more than twice the amount spent in 1980 (even after taking into account inflation)—more people have been obtaining guns. 3 The large rise in gun sales that took place immediately before the Brady law went into effect in 1994 accounts for some of the increase. 4

Three points must be made about these numbers. First, the form of

GUN OWNERSHIP, GUN LAWS, DATA ON CRIME/37

Voters Voters General General

1988 1996 population population

1988 1996

Gun ownership among voters and the general population

Figure 3.1. Percent of women and men who owned guns in 1988 and 1996: examining both voters and the general population

the question changed somewhat between these two years. In 1988 people were asked, "Are you any of the following? (Check as many as apply)," and the list included "Gun Owner." In 1996 respondents were asked to record yes or no to the question, "Are you a gun owner?" This difference may have accounted for part, though not all, of the change. 5 Second, Tom Smith, director of the General Social Survey, told me he guessed that voters might own guns "by up to 5 percent more" than nonvoters, though this was difficult to know for sure because in polls of the general population, over 60 percent of respondents claim to have voted, but we know that only around 50 percent did vote. 6 Given the size of the error in the General Social Survey regarding the percentage of those surveyed who were actual voters, it is nevertheless possible that nonvoters own guns by a few percentage points more than voters. 7

Finally, there is strong reason to believe that women greatly under-report gun ownership. The most dramatic evidence of this arises from a comparison of the ownership rates for married men and married women. If the issue is whether women have immediate access to a gun in their house when they are threatened with a crime, it is the presence of a gun that is relevant. For example, the 1988 poll data show that 20 percent of married women acknowledged owning a gun, which doesn't come close to the 47 percent figure reported for married men. Obviously, some women interpret this poll question literally regarding personal ownership as opposed to family ownership. If married women were assumed to own guns at the same rate as married men, the gun-ownership rate

in 1988 would increase from 27 to 36 percent. 8 Unfortunately, the 1996 data do not allow such a comparison, though presumably a similar effect is also occurring there. The estimates reported in the figures do not attempt to adjust for these three considerations.

The other finding that stands out is that while some types of people are more likely than others to own guns, significant numbers of people in all groups own guns. Despite all the Democrat campaign rhetoric during 1996, almost one in four voters who identify themselves as liberals and almost one in three Democrats own a gun (see figure 3.2). The most typical gun owner may be a rural, white male, middle-aged or older, who is a conservative Republican earning between $30,000 and $75,000. Women, however, experienced the greatest growth in gun ownership during this eight-year period, with an increase of over 70 percent: between the years 1988 and 1996, women went from owning guns at 41 percent of the rate of men to over 53 percent.

High-income people are also more likely to own guns. In 1996, people earning over $100,000 per year were 7 percentage points more likely to own guns than those making less than $15,000. The gap between those earning $30,000 to $75,000 and those making less than $15,000 was over 10 percentage points. These differences in gun ownership between high-and low-income people changed little between the two polls.

When comparing these poll results with the information shown in table 1.1 on murder victims' and offenders' race, the poll results imply

Categories of voters: political views, candidate the respondent voted for, and respondent's party

Figure 3.2. Percent of different groups of voters who owned guns in 1988 and 1996

GUN OWNERSHIP, GUN LAWS, DATA ON CRIME/39

that, at least for blacks and whites, gun ownership does not explain the differential murder rates. For example, while white gun ownership exceeds that for blacks by about 40 percent in 1996 (see figure 3.3), and the vast majority of violent crimes are committed against members of the offender's own racial group, blacks are 4.6 times more likely to be murdered and 5.1 times more likely to be offenders than are whites. Blacks may underreport their gun ownership in these polls, but if the white gun-ownership rate is anywhere near correct, even a black gun-ownership rate of 100 percent could not explain by itself the difference in murder rates.

The polls also indicate that families that included union members tended to own guns at relatively high and more quickly growing rates (see figure 3.3). While the income categories by which people were classified in these polls varied across the two years, it is clear that gun ownership increased across all ranges of income. In fact, of the categories examined, only one experienced declines in gun ownership—people living in urban areas with a population of over 500,000 (see figure 3.4). Not too surprisingly, while rural areas have the highest gun-ownership rates and the lowest crime rates, cities with more than 500,000 people have the lowest gun-ownership rates and the highest crime rates (for example, in 1993 cities with over 500,000 people had murder rates that were over 60 percent higher than the rates in cities with populations between 50,000 and 500,000).

For a subset of the relatively large states, the polls include enough respondents to provide a fairly accurate description of gun ownership even at the state level, as shown in table 3.1. The 1988 survey was extensive enough to provide us with over 1,000 respondents for twenty-one

White

Black

Union member in family

No union member in family

Race and union membership Figure 3.3. Percent of people by race and by union membership who own guns