Moominvalley in November (2 page)

Read Moominvalley in November Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

Tags: #General, #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Family, #Classics, #Children's Stories; Swedish, #Friendship, #Seasons, #Concepts, #Fantasy Fiction; Swedish

way up the walls looking for a way in, but they won't find one, everything is shut, and you sit inside, laughing in your warmth and your solitude, for you have had foresight.

There are those who stay at home and those who go away, and it has always been so. Everyone can choose for himself, but he must choose while there is still time and never change his mind.

Fillyjonk started to beat carpets at the back of her house. She put all she'd got into it with a measured frenzy and

everybody could hear that she loved beating carpets. Snufkin walked on, lit his pipe and thought: they're waking up in Moominvalley. Moominpappa is winding up the clock and tapping the barometer. Moominmamma is lighting the stove. Moomintroll goes out on to the veranda and sees that my camping-site is deserted. He looks in the letter-box down at the bridge and it's empty, too. I forgot my goodbye letter, I didn't have time. But all the letters I write are the same: I'll be back in April, keep well. I'm going away but I'll be back in the spring, look after yourself. He knows anyway.

And Snufkin forgot all about Moomintroll as easily as that.

At dusk he came to the long bay that lies in perpetual shadow between the mountains. Deep in the bay some early lights were shining where a group of houses huddled together.

No one was out in the rain.

It was here that the Hemulen, Mymble and Gaffsie lived, and under every roof lived someone who had decided to stay put, people who wanted to stay indoors. Snufkin crept past their backyards, keeping in the shadows, and he was as quiet as he could be because he didn't want to talk to a soul. Big houses and little houses all very close to each other, some were joined together and shared the same gutters and the same dustbins, looked in at each other's windows, and smelt their food. The chimneys and high tables and the drain-pipes, and below the well-worn paths

leading from door to door. Snufkin walked quickly and silently and thought: oh all you houses, how I hate you!

It was almost dark now. The Hemulen's boat lay pulled up under the alders, and there was a grey tarpaulin covering it. A little higher up lay the mast, the oars and the rudder. They were blackened and cracked by the passing of many a summer, they had never been used. Snufkin shook himself and walked on.

But Toft curled up inside the Hemulen's boat heard his steps and held his breath. The sound of Snufkin's footsteps got farther and farther away, and all was quiet again, and only the rain fell on the tarpaulin.

The very last house stood all by itself under a dark green wall of fir-trees, and here the wild country really began. Snufkin walked faster and faster straight into the forest. Then the door of the last house opened a chink and a very old voice cried: 'Where are you off to?'

'I don't know, 'Snufkin replied.

The door shut again and Snufkin entered his forest, with a hundred miles of silence ahead of him.

CHAPTER 2

Toft

T

IME

passed and the rain went on falling. There had never been an autumn when it had rained so much. The valleys along the coast sank under the weight of all this water that was streaming down the hillsides and the ground rotted away instead of just withering. Suddenly summer seemed so far away that it might just as well have never been and the distances between the houses seemed greater and everyone crept inside.

Deep in the prow of the Hemulen's boat lived Toft. No one knew that he lived there. Only once a year in spring was the tarpaulin lifted off and someone gave the boat a coating of tar and tightened the worst cracks. Then the tarpaulin was pulled over again and under it the boat just went on waiting. The Hemulen never had time to take it out to sea and anyway he didn't know how to sail.

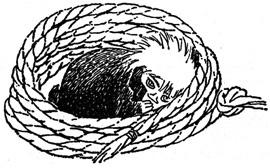

Toft liked the smell of tar and he was very particular about living in a place which had a nice smell. He liked the coil of rope that held him in its firm grasp and the unceasing sound of the rain. His big overcoat was warm and a very good thing to have on during the long autumn nights.

In the evening, when everyone had gone home and the bay was silent, Toft would tell himself a story of his own. It was all about the Happy Family. He told it until he went to sleep, and the following evening he would go on from where he had left off, or start it all over again from the beginning.

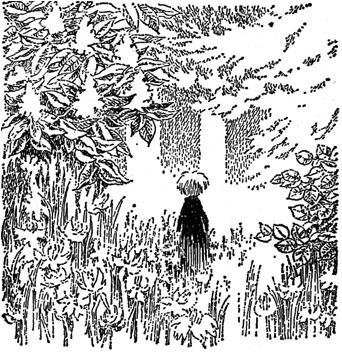

Toft generally began by describing the happy Moomin-valley. He went slowly down the slopes where the dark pines and the pale birch-trees grew. It became warmer. He tried to describe to himself what it felt like when the valley opened out into a wild green garden lit by sunshine, with green leaves waving in the summer breeze, the green grass all round him with patches of sunlight in it, and the sound of bees, and everything smelling so nice, and he walked on slowly until he heard the sound of the river. It was important not to change a single detail: once he had placed a summer-house by the river, but it had been a mistake. All that had to be there was the bridge and the letter-box. Then came the lilac-bushes and Moominpappa's woodshed, both with their own smells of summer and safety.

It was very quiet and rather early in the morning. Now Toft could see the ornamental ball of blue glass which stood on a pillar at the bottom of the garden. It was Moominpappa's crystal ball and it was the finest in the whole valley. It was a magic ball.

The grass grew tall and was full of flowers, and Toft described them to himself. He told himself about the raked paths neatly bordered with shells and nuggets in gold, and dallied when he came to the little spots of sunlight that he was particularly fond of. He let the wind sigh high above the valley and through the forest on the hillside and then die down again so that the stillness was perfect again. The apple-trees were in bloom. He put apples on some of the

trees, but then took them away again, he put up a hammock and scattered yellow sawdust in front of the woodshed, and now he was quite near the house. There was the peony bed and now came the veranda... The veranda lay basking in the morning sun, and it was exactly as Toft had made it, the rail in fretsaw work, the honeysuckle, the rocking-chair, everything.

Toft never went into the house, he waited outside. He waited for Moominmamma to come out on the steps.

Unfortunately, at that point he usually went to sleep. Only once had he caught a glimpse of her nose in the doorway, a round friendly nose, all of Moominmamma was round in the way that mamas should be round.

Now Toft wandered through the valley again. He had done this hundreds of times before and each time the excitement of going over it again became more and more intense. Suddenly a grey mist descended over the landscape, it was blotted out, and he could see only the darkness inside his closed eyes and hear the endless autumn rain falling on the tarpaulin. Toft tried to get back to the valley, but he couldn't.

This had happened quite a few times during the past week and every time the mist descended earlier. The day before it had come down at the woodshed, and now it was already dark by the lilac-bushes. Toft huddled up inside his coat and thought tomorrow perhaps I shan't even get as far as the river. I don't seem to be able to describe things so that I can see them any longer, everything's going backwards.

Toft slept for a while. When he woke up in the dark he knew what he would do. He would leave the Hemulen's boat and make his way to Moominvalley and walk on to the veranda, open the door and tell them who he was.

When Toft had made up his mind, he went to sleep again and slept all night without dreaming.