Midnight and the Meaning of Love (41 page)

Read Midnight and the Meaning of Love Online

Authors: Sister Souljah

“Do you plan on working for the military?” I asked her.

“Definitely not. I’m going to have my own company. I’m gonna be a mercenary,” she said solemnly. But I didn’t know that word, so I didn’t comment. I would look it up tonight.

“Sun’s down,” Chiasa announced.

“Let’s drink some water and split a banana. Then we’ll go out for dinner,” I told her.

“Okay, if you want,” she agreed.

“Have you ever seen this symbol?” I asked her, drawing the symbol for halal foods on a scrap of paper.

She looked at it curiously, paused, and answered, “No, but I have seen this one.” She drew another symbol. Immediately I recognized it, same as my ring, the one Sensei had gifted to me. She walked away, opened her desk drawer, and placed the same ring on her finger. “I’ve seen it on you. Now you see mine on me. It is the symbol of the Secret Society of ninja trained warriors,” she said softly. Then she added, “Comrade, please take me seriously.” She bowed her head, but not her body.

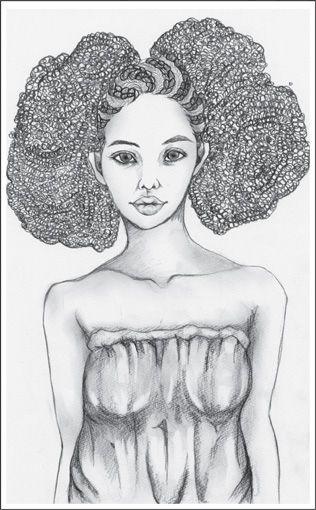

Chiasa unbraided.

* * *

Ebisu was where we ate dinner, a halal restaurant owned by some African Muslims from Senegal. Haki, the Kenyan who I met in Harajuku, put me up on it.

“It depends on what you are looking for in terms of atmosphere,” Haki said. “You will find halal foods in Shin-Okubu prepared by the Pakistanis, in Shinjuku prepared by the Indians, and in Ikekuburo prepared by the Nigerians or Bangladeshis, or in Ebisu by the Senegalese. Which one do you prefer?” Then he added with a smile, “And I see you are still here. Your one night in Harajuku has turned into two and this is only the beginning I am sure,” he joked.

The Senegalese, I knew, were similar in presentation to the Sudanese, tall, blacker than black, and regal, strong men. A delegation of Senegalese had visited my father’s estate once. While I joined and sat silently watching, I heard them joke of the ways they shared and other ways they differed. One of them boasted that my father was just getting started with his “small group of only three wives.” My father told them that it was his understanding that in Islam “Allah sets limits because it is best for us.” He then added that “Yes, I have only three wives, but they are the best three women in the world, with more purpose and value than three hundred!” My father’s words may have made them curious. However, Muslim-male-style, that delegation would for certain never get to lay eyes on my father’s wives.

Chiasa had unbraided her hair while she waited for me in Harajuku. Now it was long and thick like rope. She shook it with her fingers and wore it wild. After seeing my reaction to her “school uniform” and then the thin blouse that she tried to wear out to dinner, she knew to dress modestly. She was chilling now in a sky-blue linen dress with matching pants and blue leather sandals. She was not my woman, but I believed that when a man stands side by side with a woman, he is responsible for her in that moment. And if anyone offended her, it would be the same as if they attacked me, because

she was with me. So I believe that any woman walking in public or traveling anyplace outside her home puts all the men at risk if she is immodest and nearly naked. I knew from living in America that for me to think this way was unpopular. But my faith and beliefs as well as my heart were all homegrown, in the soil tilled and built on by my father, his father, and his father’s father.

We ate at a restaurant named Terenga. The owner, a tall, dark Senegalese wearing natural locks, greeted me with a welcoming West African smile and embrace of brotherhood. He introduced himself as Billy, a ridiculous name, I thought. I knew however, that many Muslims and people of any and all faiths in foreign lands give themselves ridiculous English names to make it easy for others to pronounce and remember. Besides, I had not told anyone my name. Of course in the telling of my true name is the name of my father, grandfather, and great-grandfather.

So the owner was “Billy” to me, no problem.

The warmth inside and the vibrant music and scent of spices created that feeling that separated Chiasa and me from the fact that we were in Tokyo. In fact it reminded me that I hadn’t heard any real music for three days! Now it was as though we had been transported to Dakar. The walls were all earth tones and the cooking station formed an aisle, which made two sections in the same restaurant. Whatever side you chose, you were unable to see the other. So all the customers gathered to one side, African-style. It was as though every customer had arrived at the restaurant in one same group and had known each other for weeks or months or even years. The owner and host, Billy, raised the topics of conversation and invited and stroked and pulled till everyone joined in comfortably, like one family.

Chiasa was hungry and didn’t seem to mind that she was surrounded by about eight African men. When we arrived, they were speaking in Wolof, the main language of Senegal. They would shift into French at times. But when I ordered our food in English, Billy switched to using English, and then everyone followed.

“So, my brother, how long have you been in Tokyo?” Billy asked me loud enough for all.

“Three days,” I told them.

“And already you are losing weight, welcome to Japan.” All the men laughed. “You have come now to the right place. We will give you

an African man’s meal, and when you have finished, no matter where you go in Tokyo, you will be banging on Billy’s door. And most of the time Billy will be here. But sometimes, Billy go out!” he dramatized in his deep voice, like my Southern grandfather. They all laughed. I looked around. “Take it easy, brother, we are all friends here. All of us are married men,” he admitted. “But we are all missing our mommas.” They laughed some more as the cooking seasonings thickened in the air and brought a fragrance that could also fill up the belly. I eased some. They were married, and for me that is a good thing.

“I figured out that if I didn’t cook my food myself, I couldn’t survive Japan; such stingy and tasteless little meals make a big man angry.” He performed, and I saw Chiasa smile. Billy’s show continued. “So I call Momma. Momma say, ‘Come home, son. I cook for you everything.’ Billy say, ‘Momma, I sent you much money today for our family. Japan is good for making money. So I stay.’ Momma say, ‘My son has to eat good food. I’ll send good Senegalese wife to cook for you!’ But Billy say noo … ‘Noo, Momma, don’t do dat!’ ” Now everyone is laughing. Billy turns to me and says, “Senegalese girl is good girl! But Japanese wife no like! In Senegal woman knows how to share and behave. In Japan Billy needs Japanese wife for

immigration

!” He hollered out the word. Two African male cooks came rushing out from the kitchen, looking startled. Meanwhile the male waiter came carrying me and Chiasa’s meal still sizzling on one large tray, same way we serve it in Sudan.

As the comedy continued, Chiasa and I cleaned our fingers with the steaming hot washcloths we were given. I whispered “Allah” over my food and began eating with my right hand from me and Chiasa’s one tray, African style. Chiasa looked at my hand and her eyes scanned the other tables. She hesitated. She opened her handbag, pulled out a pair of chopsticks, looked at them, looked around the room, and put them back.

“Before Billy married Japanese girl, he had to creep around Tokyo like dis …” Billy raised his more than six-foot frame on his tiptoes and began tiptoeing across his restaurant. “One day back then I am at apartment with friends. Police come on the block, I say, ‘Oh no!’ ”

All the African men in the restaurant stopped joking, and their laughs turned to murmurs of disapproval. It seemed all around the world African men all felt the same stab and burn when the word

police

is spoken, even more whenever cops come around. Billy continued. “First come police. Then come

immigration

police. Now I am on the fire escape crouching like a tiger. But Japanese immigration is mean and patient. They wait on the block, search on the block for six hours. When finally they leave, my legs are so painful, I cannot stand, cannot walk. I tell my Japanese girlfriend, ‘Okay! We get married.’ ” Now everyone was laughing again.

I didn’t know the particular powers of the human mind. But truthfully, my own mind was divided into at least five parts. I could hear Billy’s performance and see all his dramatic actions. He was in my fifth mind. Meanwhile, I observed Chiasa closely, considering whether or not to bring her all the way into my purpose and mission here in Japan. She was in my fourth mind. Then there was my wife, who sat in the center of my visions and made my heart move and rush and race. She was not a compromise or a convenience. She was not a plaything or an immigration decoy. She was not second to any unmarried woman I know or knew or would ever come to know. Akemi was in my third mind. The method and the fight and how to make it all happen with conflicting information and conflicting interest with a foreign tongue and on foreign land—that filled up my second mind. Then there was my Umma, my heart and my purpose. She’s always in my first mind. I needed to contact her to be sure that she was at ease and to put her mind at peace. But I was feeling a shame of a particular Sudanese kind, that I had held Akemi in my arms last night, and then let her slip away. But kidnapping and murder are capital crimes. Strategically, I knew, as Sensei had cautioned me, that Akemi needed to leave her father of her own free will, out her own front door, on her own two feet, not by climbing a tree, sliding down a back wall, crawling through a thick bush, and leaping into a back alley without any consideration. That would be no good.

Billy’s booming voice grew extra excited. My fifth mind took over the others and I listened. “In Japan an African man needs two passports! One like this”—Billy pulled his passport from his back pocket—“and …” The restaurant door opened, causing Billy to pause. It was two Japanese girls, coming through all smiles, carrying groceries. Billy seemed surprised, but he pulled them into the drama. “And my Japanese wife!” He walked over and hugged her. The male customers let out muted laughs and were obviously already familiar

with Billy’s wife. The two Japanese girls bowed to the customers and walked over to the other side of the restaurant and disappeared. Billy continued at half the volume. “If you want to be a part of it, you need

two

passports. If you want to own land in Japan, you need

two

passports. If you want to own a business in Japan, you need

two

passports. This one here,” he said, holding his passport up for all to see. “And that one there.” He pointed toward the room where his wife had walked away.

I could tell Chiasa had never tasted Senegalese food. But I could also feel that she was enjoying herself. She was reserved, and aside from her light laughter, she did not say one word to any other person in the room. I thought it was a clever position she was in. No one had to know that she was Japanese or that she spoke Japanese, unless she wanted them to. She blended in well with the Africans, because she was one. She fit in with the Japanese, because she was one. It was also interesting how she knew so much about Tokyo, its customs, its streets, it prefectures and all, but here was a place minutes from her house that she had never seen with her perfect vision. True, we were three flights up on a side street in Ebisu in the Tokyo night, but sometimes even when you know a lot about a place, there is still much to learn.

Billy was easing into his finale. He asked the African men gathered, “My wife here asked me, who is more important to you, me or your ‘mother’? So I put the question to you, my brothers, who is number one?”

All the African men stood. All were six feet tall or more. All the African men were as black as or blacker than me, all masculine and built sturdy and strong. In one chorus they all shouted, and then the shouts became a chant and they jumped and danced. “Momma, Momma, Momma!”

Billy said, “Of course it’s Momma! When my momma say to me, ‘You are a good boy, you look fresh and clean in your

jelabiyah

. You have done a good job, son,’ I smile like this.” Billy’s smile spread brightly across his face.

“No woman nowhere can top that,” Bill said and they all chanted “momma” in agreement.

The night at Terenga in Ebisu ended with a competitive game of darts. Billy had the waiters push all the tables on our side to the wall.

As new customers arrived, he had them seated on the opposite side. The dart competition heated up, and each of the eight African men became deeply serious when they took aim at the bull’s-eye mounted on a far wall.

“You are winning because you have a good luck charm,” Billy said to me, while nodding his head toward Chiasa.

“I don’t think that’s it,” I told him solemnly.

Chiasa stepped up to the board, pulled loose five darts, and stepped all the way back behind the line drawn on the restaurant floor. Without talking or smiling, she fired each of the five darts into the bull’s-eye. Amazed, the men cheered for her.

Throughout the night I saw and heard Billy speak six different languages: Wolof, French, English, Japanese, Italian, and German. He was a gracious host, a humorous man, and a Senegalese Baye Fall Muslim. He loved his momma and handled his business and was not anybody’s fool. Although I never would allow my wife to be my “passport,” I didn’t look down on him. Speaking six languages and sending his money home to his village was worthy of respect, and the way he flowed in his use of the Japanese language got me hyped. I made myself a promise that night: hiragana, katakana, three thousand different kanji, whatever. I would learn to speak Japanese fluently with that kind of ease and dexterity.