Midnight and the Meaning of Love (13 page)

Read Midnight and the Meaning of Love Online

Authors: Sister Souljah

“I don’t know. She could have known already. Maybe since Brittany’s mother goes to the same lady, she confided that to her. You never know. The fortune-teller’s goal is just to get thirty dollars from every customer. Think about it!” I scolded her.

“Uh-uh, ’cause why we went to her in the first place was because there was this lady on our block who had a son. Her little son was born with a straight line down the middle of his palm. I mean, it was a thick brown line that went straight through and over all of the other lines in his palm. Well, this fortune-teller told the lady that her son would not live past fourteen because of that line in his palm. And that boy was named Gregory Baker. He actually died on his fourteenth birthday, shot in the head at his own party by a jealous nigga. His mother told the story of what the fortune-teller had said at his funeral. So everybody in the neighborhood got worried. It was like we were all checking the lines in our palms, then going to her to get our fortunes told.”

“Bangs, you’re gonna be late getting home and I gotta go. But I want to get you some books like I said. So look around and show me what you like. I’m gonna look also. Then we’ll see.”

That’s all I could give her. I had too much on my mind to consider anything deeper, so I left it at that. I could see that she and I were worlds apart in our state of mind. We were too far to close the gap. Still, I wanted to get her started thinking differently for her sake. Muslims don’t believe that it is right to hide the knowledge and turn people away from Islam or to assume that anyone in the world cannot learn the straight and narrow path to Allah. So I had a duty to at least introduce her to the right way and leave the rest to Allah.

The faith section of Marty Bookbinder’s store was the smallest of all the shelves. Marty had told me once over a game of chess that he didn’t believe in God. I thought it was a strange confession because I knew that he was Jewish. I wondered how he could not believe in God, or for that matter Ibrahim, Musa, Jesus, and Mohammad, all prophets sent by Allah, peace be upon them. I am Muslim and we acknowledge all of Allah’s prophets. I didn’t debate Marty on his beliefs, didn’t even comment. But after that, I looked down on him some.

I was able to find two copies of the Torah, the sacred book used by Jewish people, two copies of the Holy Bible as followed by Christian people, and two copies of the Holy Quran as followed by Muslim people. He also had the Gita, which I learned was followed by some people from India, and some Buddhist text as followed by some people throughout the Asian continent as well as other places in the world. I picked up one of the two copies of

The Communist Manifesto

, which was also there. I had never heard of it and was running out of time, so I put it back and chose a Holy Quran. I also purchased a copy of a slim, two-hundred-page softcover book titled

The Muslim Woman.

Easily I decided that these were the books I would gift her. I didn’t want to think about if they were too much information for her or too difficult for her to read and understand. I just wanted to see what she would make happen in her own life.

Thinking further, Marty Bookbinder’s beliefs were different from my own, but I respected that he was comfortable providing his customers with a wide range of choices in religions and philosophies and subjects that he didn’ agree with.

It was almost closing before Bangs came up with her two book

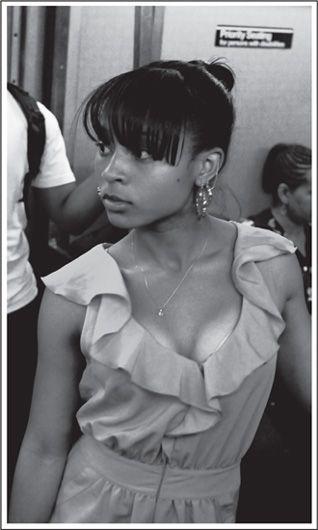

choices. For half an hour I saw her picking books up and pushing them back onto the shelves. She walked up to me with her choices, looking unsure of what she selected but so confident about her body and style. Like most women, her eyes always gave her away.

“Most of these books in here is boring,” she said casually, catching Marty’s immediate attention.

“What kind of books do you like?” Marty asked her, while ringing up my order on his register.

“I don’t know ’cause I don’t really like reading.” She was answering Marty but looking at me. “Why should I read some book when I could be out doing something?”

“Maybe if you read the right book, you’ll be out doing something better,” I told her. She smiled, stepped behind me, and leaned against the back of my body. Marty tried to act like he wasn’t watching, but he was.

“Now I see why

we

didn’t get to play chess tonight,” Marty said, while accepting and counting out my payment. I smiled and grabbed our bags and said, “Your game is better in the afternoons anyway.” Marty laughed some and followed us halfway through the door. “Nice to meet you, Tiffany. Drop by anytime. I’ll get some new books in here that you might like. Good night, my friends.”

Outside I handed Bangs her new books. She took them and stuffed her grandmother’s dress in the bag also. “It seems like you are always giving me something, Supastar. When you gonna give me what I really want?”

“Slow down, shorty,” I told her calmly.

She jumped up once, then shook her whole body and stamped each foot, throwing a temper tantrum. “How could it get any slower?” she asked. “You got me waiting, waiting, waiting. It be different if nobody wasn’t getting it,

but I know somebody is getting it.

It’s just not me! Here, take this. I want to give it to you.”

She pointed to her front right jeans pocket. Her jeans were so tight, I could see from the impression that she had something in there. I wasn’t falling for what she wanted, me to put my hand in her snug pocket. That would be too much for me and she knew it. I didn’t respond. She used her slender fingers to drag it out.

“Those are my feelings.” It was the music she had been listening to on her Walkman, I figured.

“Nah I’m good,” I told her, believing that in this case accepting her music would be the same as accepting her feelings for me. She leaped up and pushed the music in my pocket and laughed and ran. Now she wanted me to chase her. When I didn’t, she ran back to me.

I checked my Datejust. “You got nine minutes to get home on time, Bangs,” I reminded her.

“If you give me a kiss, Supastar, you don’t have to walk me back. I promise I’ll run straight home and beat the motherfucking clock!” She smiled mischievously, rocking back and forth on her Reeboks and then shifting side to side. She was always bursting with energy and couldn’t keep still for more than a few seconds.

“I’ll walk you back,” I said, a subtle way of declining her enticing kissing offer. “But I’m not going inside your house, I’m telling you now. Matter of fact, I’ll take the shortcut up to the back of your house. Then I gotta break out. I got something important to do.”

“You won’t say hi to my grandmother? She likes you

so much.

She asks about you all the time. Since you don’t come around, Grandma be asking me, ‘What did you do wrong to him?’ And she been feeling sick lately. If she saw us together, she would probably cheer up.”

“Nah, it’s late. If she’s sick, she should sleep. Don’t give her a hard time either. If she’s sick, you should be taking care of your baby instead of leaving her in the house.”

“Oh, you remember my daughter?” Bangs said sarcastically.

“Who forgets a baby?” I asked. “Besides, your milk …,” I said, pointing to the spot on her thin blouse.

“I know. Every time it’s time for her to suck, no matter where I’m at, my milk starts leaking and shooting out.” She laughed at herself, a little embarrassed. But she didn’t need to be embarrassed about that in front of me. It was that kind of thing that seduced me the most. It was being up close, and seeing and feeling that, that caused me to stay away. But she kept coming back.

At the back of Bangs’s house I watched as she walked slowly on purpose through the alleyway that led to the front. She knew I was watching, so she swang her hips more for me. She kept glancing back at me and smiling. Soon as she stepped to turn the corner onto her stoop, I left.

I was close to the subway about to go down the stairs when Bangs came racing back without her bag of books. “They took her,”

she said, stopping short and her face the opposite of how it was only seconds ago.

“My grandmother! The ambulance came and took her.” Bangs was gasping, and tears were welling up in her eyes.

“Then she gotta be at the closest hospital. Take it easy. Did you lock up your house?” I asked her.

“No, I never went in the house. My neighbor, Mrs. King, was sitting right there on my stoop waiting for me. She said the ambulance came and took my grandmother, and that my uncle took the baby!” Her body began trembling. “Mrs. King said that she had offered to hold the baby till I got right back, but my uncle said no and took my daughter. Mrs. King said she didn’t argue with him ’cause she could smell the liquor on him and didn’t want him to start acting crazy like she knew he would. I’m gonna kill him!” Bangs spoke with a forceful tone but not a loud voice, as though she truly meant it.

“He probably went up to the hospital to see about your grandmother. She’s

his

mother, right? Don’t worry. He’ll bring the baby right back. What’s he gonna do with an infant who needs breast milk?” I said, trying to console her. But she gave me a flat stare. Without any words, she reminded me with her eyes that her uncle was her rapist. Her uncle was a man who never worried about pleasing his mother or protecting his family. In fact, he was the biggest threat to all of them. And except for her trembling, Bangs was finally standing still, face stiff with anger, spilling hot tears.

“He didn’t take the baby to keep her safe. He took her to control me, to make me do whatever

he say.

That’s what

he does.

He wouldn’t even go and check on Grandma. That’s how he do,” she said, as though she was 100 percent sure that she was right.

I checked my watch but I really didn’t have to. I knew for certain it was time for me to go get Umma. I peeled a twenty from the pile I had in my pocket and handed it to Bangs. “Take a taxi to the closest hospital. Go and check everything out first, before you panic.”

“Are you coming with me?” she asked, as I knew she would.

Her uncle is the baby’s father

, I thought to myself about the sickening truth. And even though I felt for Bangs, and hated her uncle and liked her infant daughter and grandmother, I put Umma first,

my mother

and

my purpose.

I left.

SON, FATHER, GRANDFATHER

Back at our apartment, after Umma was sleeping, I sat down on my bed thinking about my life while holding the new Sony Handycam that Ameer and Chris had bought for me. It was the latest model, an HDR-XR100. Studying the device, the buttons and attachments, I unfolded the user’s manual and glanced it over. Akemi didn’t like cameras too much, I believed. As an artist, her eyes and mind were her camera, and her gifted hands recreated the images that her eyes and mind saw through drawings and paintings.

How do I feel about cameras?

I wondered to myself. I had never relied on them and neither had my father or grandfather. The images of my past in the Sudan were bright and colorful and powerfully clear, as though I could step right inside them and begin reliving every scene. But if I had known that there would be so many miles and meters between my father and grandfather and me, separated by continents, would I be happier if I had filmed them and could project them right onto the wall of my bedroom? Would Umma be happier if she could see my father on film when she was sitting all alone in her bedroom? Would Naja be happy if she could see a moving picture of our father instead of having to move her imaginings around in her head, full of the flaws of not really knowing or even having the pleasure of remembering?

A smile stretched across my face naturally when I thought of my Southern Sudanese grandfather. He wouldn’t even give me the option of taking his photo or filming him. He was an expert at refusals. When he said no he meant it, no negotiations or backpedaling. In fact he only had one picture on the wall of his hut. It was of a European

missionary man who, Southern Grandfather said, came from Europe “talking that Jesus talk with his eyes on our women and foot on our land and hands all over the place.” The missionary man’s photo was posted right beside a few locks of his blond hair and a rawhide strip with the missionary’s teeth, fingers, and toes and his dried-out “lying tongue” dangling in the middle like a flesh jerky pendant. My grandfather, a respected elder and counsel in his village, husband of six wives and father of nineteen children, my father the youngest one, only wore his necklace featuring the missionary’s demise when he needed to remind ambitious villagers or intrusive outsiders of what he was capable of and how much influence he carried and how fearless he was in the face of the British or of the presumptuous Arabs, or any pushy intruders, for that matter.

My Southern Sudanese grandfather’s voice was so deep, he made the walls rattle and the snakes slide and escape deep into the ground. He never ate refrigerated or frozen foods, drank his milk straight from the udder. He never had ice cream or pizza or any modern food inventions, not because he couldn’t, but strictly because he didn’t want to. He was not a friend to change and believed that

change

and

progress

were two completely different words.