Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece (20 page)

Read Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece Online

Authors: Donald Kagan,Gregory F. Viggiano

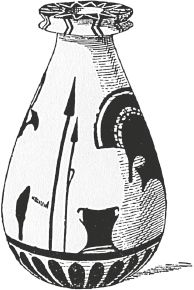

The fading paint has caused most of the spears to disappear, but there is no indication that any soldier had a second spear. All ten warriors on each side hold shields with blazons, including flying birds, bulls’ heads, a lion’s head, and a hare; all wear Corinthian helmets with crests, and greaves, and the left-hand man of each group, the only men whose torsos are visible, wear corselets. Lorimer inferred corselets where the border of a chiton is visible. The equipment is thus typical of the hoplite, although, as in the whole Protocorinthian battle series, there is not a single representation of a sword or dagger, which every man presumably carried.

15

This is the first image that shows lines of hoplites with significantly overlapping figures, and this has generally been interpreted as an indication that the artist is trying to represent a high-density formation, specifically closely spaced organized ranks, as in the classical phalanx. It has been suggested, however, that what appear to be straight ranks may rather be stylized images of dense but irregular crowds, and it has been pointed out that the spacing of the different groups of figures on this aryballos varies. Van Wees argues that the closeness of the men on the far left and their short

stride indicate that “they are standing still, packed tightly together,” while the wider strides of their opponents suggest that the enemy is “moving towards them in rather more open formation.” In the central groups, the even more generous spacing and long strides of the men suggest “a much looser order as the troops briskly advance into battle.”

16

He suggests that even the densest of these formations, on the far left, may not represent a regular phalanx, but rather an irregular stationary crowd massed together in defense, as occasionally described in the

Iliad

(“leaning their shields against their shoulders, raising their spears,” 11.592–5; also 13.126–35, 152).

17

FIGURE 2-6. Battle frieze from the Berlin aryballos. Middle Protocorinthian, c. 650 BC. Berlin 3773; drawing after E. Pfuhl,

Malerei und Zeichnung der Griechen

(Munich, 1923), no. 58. Redrawn by Nathan Lewis.

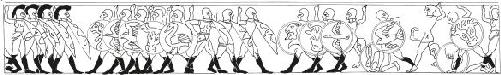

The Macmillan aryballos (

fig. 2-7

), ca. 650, was painted by the same artist as the Berlin aryballos and the Chigi olpe. Nine figures moving from right to left are apparently in the process of defeating nine opponents. From the right, the first five victorious hoplites are dispatching four opponents who have fallen to their knees in flight. The sixth hoplite on the winning side is meeting with resistance from a retreating enemy. The seventh hoplite has exceptionally been defeated by an opponent on the side that is otherwise losing. The final group on the far left shows another two victorious hoplites driving back two retreating opponents who are evidently trying to cover a wounded comrade collapsed behind them. All wear Corinthian helmets and greaves; almost all, including the defeated, carry two spears.

This is the first scene in Greek art to represent a collective rout and pursuit; in classical hoplite battle, a rout almost always meant defeat without any chance of rallying and resuming the fight, so the attempt to portray this crucial moment may reflect the emergence of the phalanx.

18

On the other hand, rout and pursuit are inevitably part of most kinds of infantry combat, and are frequently described in the

Iliad

in a manner similar to the image on this vase, that is, as a series of hand-to-hand combats in which the casualties are all on one side, even if a few put up some resistance (e.g., 5.37–84; 16.306–56).

19

Supplication of the victor by a defeated soldier is also a new feature; it is prominent in epic (e.g.,

Il

. 21.72ff.) and might be a “heroic” feature, as Lorimer suggested, but could equally reflect contemporary practice. Again the use of two spears, in the Homeric manner, could be either a heroizing element that “crops up to mar the perfect picture of hoplite equipment”

20

or else an indication that mid-seventh-century hoplites were indeed still equipped in this way, and sometimes used spears for throwing.

21

FIGURE 2-7. Battle frieze from the Macmillan aryballos. Middle Protocorinthian, c. 650 BC. British Museum, London 1889.4-18.1; drawing after

JHS

11 (1890), pl. II 5.

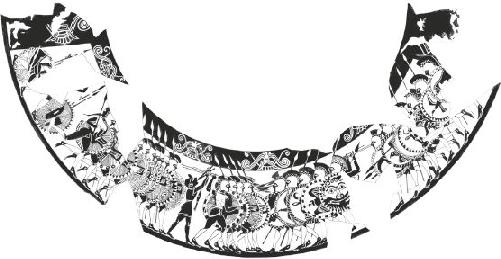

FIGURE 2-8. Chigi vase. Middle Protocorinthian olpe from Veii, c. 640 BC. Museo di Villa Giulia 22679. Redrawn by Nathan Lewis.

Most complex of all surviving battle scenes in seventh-century art, the Chigi vase (

fig. 2-8

) shows four groups of hoplites, two on each side, about to engage in combat. On the far left, two men are arming themselves. Each of the hoplites carries two spears, one in the right hand and another, apparently larger, in the shield hand. Snodgrass has refuted Lorimer’s attempt to explain these second spears as representing an extra rank of hoplites not shown: “contrary to what she says, in the original illustration of the scene in

Antike Denkmaler

, the shafts of at least two of the spears are visible, passing across the shields of the main group of the left, and grasped in their left hands together with the

antilabe

.”

22

The men arming on the far left each have two spears planted in the ground beside them, and here it is clear not only that the spears are of unequal sizes but also that they have throwing loops attached to their shafts.

This is the first scene, and one of the very few scenes ever, to show hoplites in more than one rank, and as a result scholars since at least Nilsson have regarded the Chigi vase as the first undeniable depiction of the classical phalanx; Snodgrass describes the image as follows: “the men fight in close-packed ranks; they advance and join battle in step, to the music of a piper; they balance their first spear for an overhand thrust; they are all equipped with Corinthian helmet, plate-corselet, greaves and hoplite shield.”

23

But the image raises some questions. First, if, as Snodgrass pointed out, the two front ranks of hoplites are raising the smaller of their pairs of spears with loops, the implication seems to be that they are preparing to throw. The two sides, despite standing so close together, would thus be engaging in missile rather than hand-to-hand combat.

Van Wees concludes that “whether we have here a picture of close combat with the wrong weapons, or of missile warfare at the wrong distance, we do not have a picture that matches the classical phalanx.”

24

Second, van Wees observes the extra pair of legs in the front line on the left. He doubts that this can be a careless mistake by the meticulous Chigi Painter. He also notes the redundant spear in the other army (i.e., the third, shorter, upright spear that protrudes behind them), which “must belong to some other, unseen hoplite. In other words, these rows of overlapping figures are not realistic images of single ranks, but schematic representations of larger groups of hoplites—whether in regular formations or bunched together, we cannot tell.”

25

Third, he points out that the second rank of hoplites is in each case larger than the first, and is not marching in step with the men ahead of them, but “unmistakably

running

.” The running hoplites on the left, moreover, are still carrying their spears upright rather than leveled, which may suggest that they are imagined as farther from the front than the second rank on the right, which has begun to level its spears. His overall interpretation of the scene is as follows:

In the centre, two groups of hoplites are about to join battle and throw javelins at one another. The army on the right is about to be reinforced by a larger group of hoplites who have come running up and are just raising their spears to join the fray. In danger of being overwhelmed, the troops on the left call for help in turn, but their reinforcements, the largest group of all, still have some way to run, and indeed some are only just getting armed. The role of the piper in this scenario is not to set a marching rhythm, but to sound a call to arms, as trumpeters do elsewhere: this explains why he is evidently blowing at the top of his lungs, and why we see no piper on the other side, which has the temporary advantage.

26

On this interpretation, the Chigi vase does not, after all, represent a classical hoplite phalanx, but a stylized version of the scenes of escalating combat by sizable but irregular crowds of warriors that one finds described in the

Iliad

(e.g., in the sequence at 13.330–495; men arming while their comrades are already fighting has a parallel at 13.83–128).

27

Van Wees thus contends that these three remarkable vase paintings “prove nothing about the existence of a fully developed phalanx.” Unlike earlier Greek art, they show armies moving into battle and armies in flight and pursuit, as well as “an unprecedented degree of overlapping between figures to create an impression of density.”

28

However, van Wees sees closer analogies to Homeric battle narratives than to the classical phalanx in the work of the Chigi Painter.

Further explicit evidence that hoplites in the seventh century were sometimes armed with throwing spears comes from the alabastron from Corinth (

fig. 2-9

). The still-life arrangement of a hoplite’s equipment shows both a long (i.e., thrusting) spear and a shorter javelin with a throwing loop. The fact that this appears in a still life rather than a battle scene makes it unlikely to be a “heroic” feature. “It seems an inescapable conclusion,” Snodgrass argues, “that the early hoplite often, though not invariably, went into battle carrying two or more spears; and it is very probable that one at least

of these was habitually thrown.”

29

He also argues that the use of throwing spears in the Geometric age “took such a strong hold on current practices that the advent of the heavy infantry panoply, and even of the rudimentary hoplite phalanx, did not at first expunge it.”

30

It is not clear how the use of throwing spears by hoplites was compatible with a dense phalanx formation—which in classical times engaged only in hand-to-hand combat—and it could be argued that the use of this weapon implies a more open and fluid formation even as late as 625 BC.