Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece (18 page)

Read Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece Online

Authors: Donald Kagan,Gregory F. Viggiano

176

. Cf. Cartledge (1977, 22).

177

. Salmon, 95.

178

. Salmon, 99.

179

. Salmon, 99.

180

. Salmon, 101.

181

. Hans van Wees, “The Homeric Way of War: The Iliad and the Hoplite Phalanx (part II),”

Greece & Rome

41.2 (1994), 155 n. 100.

182

. Van Wees (1994, 155 n. 100).

183

. Peter Krentz, “The Nature of Hoplite Battle,”

Classical Antiquity

4 (1985), 50–61.

184

. Krentz, 61; Krentz sites the painting by the C painter on the bowl of a tripod-pyxis in the Louvre to support his thesis. See illustrations.

185

. Krentz, 53.

186

. Krentz, 53.

187

. Krentz, 54.

188

. Krentz, 59–60; Snodgrass conceded Salmon’s point in A. Snodgrass,

Archaic Greece

, Berkeley, 1980, 106.

189

. Krentz, 61.

190

. G. L. Cawkwell, “Orthodoxy and Hoplites,”

CQ

39 (1989), 375–89, 389.

191

. Peter Krentz in this volume discusses the nature of the

othismos

and the orthodoxy’s use of the rugby analogy, which Cawkwell discusses in detail.

192

. Penguin translation by T. J. Saunders.

193

. Cawkwell, 379; Xen.

Anab

. 6.1.11.

194

. Cawkwell, 381.

195

. Cawkwell, 381.

196

. Cawkwell, 384.

197

. Cawkwell, 384–85.

198

. Cawkwell, 386–87.

199

. See the introduction in this volume.

200

. In the second edition of his classic study,

The World of Odysseus

, originally (1954) written close to a decade after Lorimer’s article on hoplites, Finley (1977, xxi) commented on the delayed impact that theories of oral composition had had on Homeric studies: “About oral poetry and its techniques, in contrast [to the negligible changes made to the rest of the first edition], the alterations (in the first two chapters) are significant, though not numerous. I originally wrote at a time when the discoveries of Milman Parry, which revolutionized our understanding of heroic poetry, had just been digested by scholars in the English–speaking world, and were still largely ignored.”

201

. Lorimer, 113.

202

. Finley, 21.

203

. Anthony Snodgrass, “An Historical Homeric Society?”

JHS

94 (1974), 114–25.

204

. Cartledge (1977, 18 n. 59).

205

. Paul Cartledge,

Spartan Reflections

, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2001, 157.

206

. Anthony Snodgrass, “The ‘Hoplite Reform’ Revisited,”

Dialogues d’ Histoire ancienne

19 (1993), 47–61, accepts this aspect of Latacz’s argument.

207

. Van Wees (1994, 131–55, 143–44).

208

. Van Wees (1994, 145–46).

209

. Van Wees (1994, 148).

210

. Van Wees (1994, 148).

211

. Van Wees (1994, 131).

212

. Hans Van Wees, “Kings in Combat: Battles and Heroes in the

Iliad

,”

CQ

38 (1988), 1–24.

213

. Van Wees (1988, 14).

214

. Hans Van Wees,

Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities

, London, 2004, 157; see

Iliad

4.446–56 and 11.90–91.

215

. Hans Van Wees “The Development of the Hoplite Phalanx: Iconography and Reality in the Seventh Century,” 149, in Van Wees, ed.,

War and Violence in Ancient Greece

, London, 2000, 125–66; scholars have dated Tyrtaeus as early as 680.

216

. Van Wees (2000, 149).

217

. Emphasis that of van Wees (2000, 150).

218

. Van Wees (2000, 151);

Iliad

4.112–14; 8.266–72; 15.436–44.

219

. Van Wees (2000, 155).

220

. Van Wees (2000, 156); for a more detailed discussion see van Wees (2004, 166–83, 195–97), which tries to show that the phalanx did indeed develop c. 550–450 BC.

221

. Hans van Wees,

Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities

, London, 2005.

CHAPTER 2

The Arms, Armor, and Iconography of Early Greek Hoplite Warfare

GREGORY F. VIGGIANO AND HANS VAN WEES

The Greek Hoplite (c. 700–500 BC)

Although elements of the bronze panoply associated with the classical hoplite began to appear in the late eighth century, what set the hoplite apart from his predecessors was above all his distinctive heavy wooden shield with a double handle, which is first attested circa 700 BC (see below,

fig. 2-4

). This date may therefore be regarded as the beginning of the hoplite era. A great deal of the debate about the origins of the classical phalanx centers on what the adoption of this type of shield might imply about the nature of hoplite fighting and battle formations.

The Hoplite Shield

The simple scene of combat shown in

figure 2-1

is representative of a very common type in archaic vase painting. It is a scene from heroic legend—explicitly identified by captions as Menelaus facing Hector over the dead body of Euphorbus (described in the

Iliad

17.1–113)—but the combatants are equipped with the panoply of the contemporary hoplite. It is included here primarily to illustrate the nature of the double grip of the hoplite shield, as shown on the figure on the left: the shield has a central metal armband (the

porpax

), through which the bearer thrust his left forearm up to the elbow, and a hand grip (

antilabe

), at the rim of the shield, that he grasped with his left hand.

It is worth noting that in archaic art the hoplite shield is almost always shown in scenes like this, used by combatants who are “dueling” or otherwise engaging in what looks like combat in a quite open order, rather than in a regular, close formation of the classical type. On a view widely adopted since the study of Lorimer, all such images show a combination of contemporary arms and armor with unrealistic “heroic” combat tactics. Alternatively, it could be argued that early hoplite tactics were not yet like those of the classical phalanx and that both the equipment and the manner of fighting shown on the vases may reflect contemporary reality.

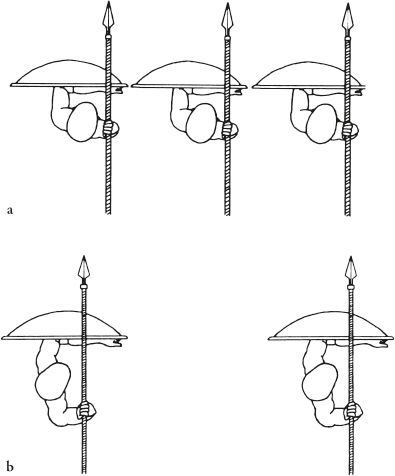

The common view is that the double-grip hoplite shield could be effectively employed only in a dense formation because the bearer used the protection of only half the shield, leaving him vulnerable on his right unless he exploited the cover of the “redundant” half of his right-hand neighbor’s shield, as shown in

figure 2-2a

. If so, the presence of the shield implies the existence of a close-order phalanx in which the intervals between men are such that their shields nearly touch, that is, about three feet. On Victor Hanson’s view, the shield was adopted to meet the needs of an already existing form of massed combat; more commonly, it has been argued that the invention of the shield immediately, or in the course of some fifty years, brought about the adoption of close-order formations. Others, by contrast, have argued that the double-grip system was invented primarily to enable warriors to carry heavier shields that offered more protection, and that the hoplite shield could be used without serious disadvantage in more open formations. In particular, van Wees has suggested that hoplites stood sideways (left side forward) when in close combat with their opponents, as shown in

figure 2-2b

, and that in this position they would make full use of the cover of their entire shield, leaving no “redundant” section and thus little opportunity or need for men to rely on the shelter of their neighbor’s shield. He argues that this pose is both the more natural stance to adopt in fighting with a spear, and is frequently shown in Greek art; see

figures 2-2c

and

d

.

1

If so, the hoplite formation could have been more open, with intervals of, say, six feet between soldiers, which are attested elsewhere and would have allowed room for brandishing spear and sword, as well as for some movement between

the lines, without losing the cohesion of ranks; in archaic hoplite combat, the formation may have been still more open.

FIGURE 2-1. Rhodian plate, c. 600 BC. London, British Museum 4914. Redrawn by Nathan Lewis.

Other significant features of the large wooden hoplite shield are its more limited maneuverability compared with the single-grip shield and its greater weight compared with a variety of types that were smaller and/or made of lighter materials such as leather or wicker. A hoplite shield could be held out no farther than the length of the upper arm, whereas a single-grip shield could in principle be held out at arm’s length, though if it was carried on a strap (

telamon

) the range of its forward movement was in practice limited. The hoplite shield could not be brought over to the right-hand side as far as a single-grip shield, though in practice the lateral range of the latter was restricted by how much space the bearer needed in order to wield the spear or sword in his right hand. A hoplite shield was not carried on a

telamon

and could thus not be slung across the shoulders, as a single-grip shield on a strap could; it thus offered no protection for one’s back in retreat or flight, though the bronze corselet, which was introduced at the same time, would have at least partly compensated for this.

2

The greater weight of the hoplite shield made the bearer less mobile, but how much less mobile depends on one’s estimation of its actual weight (see Krentz,

chapter 7

this volume), and literary and iconographic evidence show that it did not stop hoplites from being able to charge into battle at a run (see

fig. 2-2e

and the Chigi vase,

fig. 2-8

).

Many scholars argue that the cumulative effect of the above factors was enough to make the bearer of a hoplite shield a largely static fighter who relied heavily on the protection of a close-order formation. For some, however, the effect of the shield was primarily to provide much greater frontal protection, and neither the reduced mobility nor the reduced protection for the right flank and the back were significant enough to produce (or reflect) a fundamental change in manner of combat. On this latter view, “If this change to the shield did not necessarily entail a change in formation, it does suggest that in the late eighth century BC the trend in warfare was towards more frequent or prolonged hand-to-hand fighting, where improved protection was vital since blows landed with more force and were less easily dodged than in missile exchanges.”

3

Finally, Victor Hanson has argued that the bowl-shaped hoplite shield was particularly well suited to physical “shoving” of the enemy: the bearer could lean his shoulder into the hollow of the shield and thus push with his whole bodily weight against the enemy, or into the back of the comrade in the rank ahead of him.

4

Krentz, however, has argued that most references to “pushing” refer to a forward drive in combat, not to a physical shove,

5

and van Wees has suggested that hoplite shields were tilted back (see

figs. 2-2e

and

2-2f

), so that the upper rim rested on the shoulder and the lower rim pointed outward, and any physical “pushing of shields” could not have involved shoving with one’s whole bodily weight into the shield, but rather “shoving the protruding lower part of one’s shield against the corresponding part of the enemy’s shield—with the aim, no doubt, of driving him back, disturbing his balance, or at least breaking his cover.”

6

The rear ranks would not engage in this type of pushing, but played a more passive role, including replacing fallen or tired men from the front ranks.