Map of a Nation (20 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

B

EFORE LONG, ACCOUNTS

of William Roy’s death reached the

drawing

room of Goodwood House, a semi-octagon of brick and flint at the centre of a vast estate just inland from the Sussex coast. Goodwood belonged to Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, the great-grandson of Charles II and that king’s mistress, the ‘young wanton’ Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth. By July 1790 Charles Lennox was fifty-four years old and somewhat worn out. He retained the muscular figure of his youth, but his jowls were sagging and his hair was greying and thinning. News of Roy’s demise is likely to have affected him deeply. The two men had

experienced

wildly different upbringings: Roy was the son of a land-steward, Lennox the offspring of a duke, the employer of numerous estate managers of his own and the owner of vast property in London, Sussex and the Loire Valley in France. But the two men’s lives had often converged and Lennox had publicly celebrated Roy during his lifetime as an ‘excellent and

universally

esteemed officer’.

In the months that followed Roy’s death, Lennox took up the cause that Roy had owned ever since his experience on the Military Survey of Scotland: the conviction that ‘the honour of the nation’ depended on creating ‘a map of the British islands’ that was ‘greatly superior in point

of accuracy to any that is now extant’. William Roy’s own

recommendations

and supplications had mostly fallen on deaf ears during his lifetime. But by 1790, Charles Lennox – aristocrat, politician and Master-General of the Board of Ordnance – possessed sufficient power to transform those recommendations into reality. It was through Roy’s imagination and ambition and Lennox’s clout that the Ordnance Survey finally came into being.

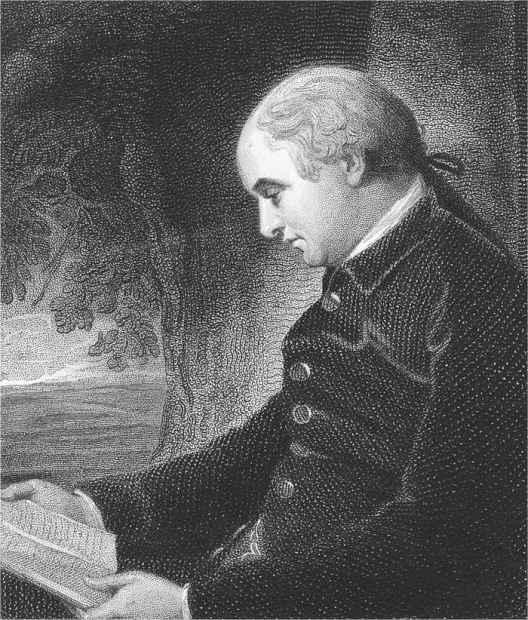

18. Portrait of Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, by William Evans, after George Romney, 1808 (1776).

C

HARLES

L

ENNOX HAD

been fascinated by maps since childhood. His father had encouraged all his children to read widely in geography, travel-writing, history and natural philosophy. Inspired by this education, Lennox’s sisters went on to encourage their own offspring to enjoy surveying and topography, often using the wooden jigsaw maps that were a popular early aid to geographical education. (Jigsaws as we know them were invented in Britain in the 1760s by the London map-maker John Spilsbury. All these first jigsaws took the form of maps, and were designed as educational aids. In Jane Austen’s novel

Mansfield Park

(1814), the heroine Fanny Price was mocked for her inability to ‘put the map of Europe together’ using one of these jigsaws.) The Lennox sisters’ love of maps lasted a lifetime. By 1808 Charles’s younger sister Sarah had lost her sight, but she was thrilled when her son constructed an early form of Braille map that allowed her to

visualise

the events of the Napoleonic Wars. He depicted Spain and Portugal by fixing raised patches of cardboard to the map and ‘contrived by little pebbles to mark out the different places by feeling, very cleverly; the rivers by bits of twist. The result is that she feels out any place she wants to find in a minute and diverts herself for hours with it.’

Charles Lennox was even more actively engaged with cartography than his sisters. Practical map-making skills were an important component of eighteenth-century aristocratic male education and in Lennox’s case this was augmented by a thorough education in trigonometry at the University of Leiden. In the 1750s, when Lennox was on the Grand Tour, his chaperone and tutor Abraham Trembley helped him to practise surveying on Europe’s major battlefields. On his return to England, Lennox straight away commissioned a map of Richmond in Yorkshire.

On coming of age, Lennox began to buy up the properties that surrounded his estate. Originally 1100 acres, Goodwood gobbled up its neighbours:

Halnaker House and Park, Westhampnett House and its adjoining land, West Lavant, Raughmere, Stoke, Singleton, Charlton, East Dean and Selhurst Park. Soon the estate was almost seventeen times its initial size. Lennox then ruthlessly ‘improved’ his new monster territory. He envisaged

pleasure-gardens

, a ‘high wood’ in which exotic birds sang, a working mill to produce mortar from the estate’s sandpits, a secluded ‘pheasantry’, heated lodges for tenants and employees, and acres of forests, rare trees and imported plants. (Lennox’s improvements were precursors of the current multifunctional estate, still owned by his heirs, which incorporates a hotel, spa, farm, forest, aerodrome, golf course and sculpture park, and hosts vintage car rallies and horse races.) With the help of an architect, Lennox also set about converting the old Goodwood House. Later he turned his attention from his own

creature

comforts to those of his beloved hunting dogs and erected ornamental kennels within sight of the house, at a cost of

£

6000.

Lennox’s early interest in cartography and the ambitious plans he

entertained

for his estate’s improvements prompted him on 1 November 1758, shortly after his marriage to Lady Mary Bruce, to offer a young Dutch surveyor called Thomas Yeakell full-time, permament work as his estate surveyor. Landowners frequently commissioned map-makers to make

one-off

charts of their estate but it was extremely unusual to employ a surveyor on a long-term basis. Lennox arranged for Yeakell to be tutored by the Royal Military Academy’s mathematics professor and then, at the beginning of 1759, the aristocrat set off on a four-month tour of Holland and Germany, taking his map-maker with him. On his return to Britain in July, Yeakell was prolific. Over the next four years, this young surveyor made hundreds of maps and sketches of Goodwood, perfecting his methods and draughtsmanship and paying careful attention to every fold and indentation of the landscape.

I

N

1763 L

ENNOX

decided that his vast estate was too big for Yeakell to survey alone, so he employed James Sampson, who ‘gave proofs of an

extraordinary genius for drawing’. Lennox found Sampson stimulating

company

. He was a charismatic young man who spent his leisure hours in the British Museum copying its artefacts and chatting to visitors. Lennox was so taken with his new estate surveyor that he introduced Sampson to his

father-in

-law, Henry Seymour Conway, a senior military officer and politician. Conway also responded to the map-maker favourably and before long Sampson had married one of his senior servants and was enjoying the free run of his enormous house.

But James Sampson had a dark side. As newspapers would later report, he ‘maintained an illicit intercourse with some women of debauched principles, whose extravagances involved him in many embarrassments’. Short of funds, and learning that Conway hid money and valuables in a desk drawer in his library, Sampson hatched a plan. He plotted to steal Conway’s cash and set fire to the library to disguise his crime. At six o’clock one morning in August 1766 Conway awoke to the cry of ‘Fire!’ and the smell of singed vellum. When a team of fire-fighters arrived, he frantically directed them to recover the bureau. Most of the desk had been reduced to ash but Conway’s secret drawer was miraculously intact and he gratefully retrieved its contents. But when the confusion had died down and Conway examined these papers properly, he found that a banknote for the enormous sum of

£

500 and four

£

100 notes were missing. Conway realised at once that the fire was designed to conceal the robbery.

Conway contacted his bank, who informed him that his large note had already been exchanged. But the two clerks who had managed the

transaction

clearly remembered its bearer and, from the physical description they offered, Conway suspected Sampson. He passed this information on to Lennox, who summoned the map-maker to his home ‘on business’. Chattering away to Lennox ‘on different subjects’, Sampson was unaware of the clerks’ concealed presence in the room. Recognising Sampson instantly, they made a signal to Lennox, who then accused his young surveyor of theft and arson. Sampson initially prevaricated but soon ‘confessed all the

particulars

of his guilt’. He was committed to Newgate and eighteen months later, on 11 March 1768, this rash young map-maker was executed at Tyburn.

Charles Lennox’s bad experience with James Sampson did not, however,

stop him from employing more surveyors at Goodwood. He replaced Sampson with a 24-year-old map-maker called William Gardner, and this appointment was an entire success. Lennox’s long-serving estate surveyor Thomas Yeakell struck up a professional and personal relationship with Gardner which endured until Yeakell’s premature death in 1787. The alliance would be recognised as one of the most important in British

cartographical

history.

Throughout the late 1760s and 1770s, Yeakell and Gardner’s joint

responsibility

was to make accurate maps of Lennox’s property. They covered the full seventy-two square miles of his enormous estate with loving intimacy, on the expansive scale of six inches to a mile. But it soon became apparent to Yeakell and Gardner, and to Lennox too, that mapping Goodwood was no longer enough to occupy two surveyors on a full-time basis. Yeakell and Gardner instead began to dream of making a really accurate map of a substantial portion of the British landscape, based on a triangulation and draughted on the scale of two inches to a mile. This would be twice as detailed as the maps submitted to the Society of Arts’ competition. Yeakell and Gardner anticipated that their map of Sussex would

not only contain an accurate plan of every town and village, but every farmhouse, barn, and garden, will have its place. Every inclosure … with the nature of its fence, whether bank, ditch, pale, or wall, will be described; every road public or private, every bridle way will be traced. The hills and vallies will be clearly distinguished from the low lands, and their shape and even height made sensible to the eye.

This was an almost unprecedented level of information for a county map to display.

Yeakell and Gardner’s resulting ‘Actual Topographical Survey of Sussex’ is a stunningly intricate image of mid-eighteenth-century Sussex. Field boundaries lattice the county’s plains and promontories stretch into the sea. The settlement of Chichester is a red weal on a tea-coloured landscape. As the northern part of the county rears up into the South Downs, black hachures trace the shadow of its slopes and declivities. And nestling in the crook of these hills, depicted in resplendent green, is the delicate, elaborate outline of Lennox’s Goodwood estate. Only the four southern sheets of the

projected eight of Yeakell and Gardner’s ‘Great Map’ were eventually

published

, between 1778 and 1783. Sales were rather poor (probably due to its costliness), but Yeakell and Gardner’s ‘Great Map’ undoubtedly raised the bar for subsequent map-makers.