Manhattan Mafia Guide (23 page)

Read Manhattan Mafia Guide Online

Authors: Eric Ferrara

On August 8, 1949, John the Bug was sentenced to six years in prison based on the testimony of a fingerprint expert, who claimed to have lifted a partial print of Stoppelli’s ring finger from an envelope of heroin confiscated during an Oakland, California hotel room raid. The only problem was that Stoppelli had proof that he was three thousand miles away in New York City, where he checked in with a parole officer.

Despite contradicting evidence, Stoppelli was convicted. In November 1951, the FBI examined the print in question and concluded that it was not Stoppelli’s. President Harry S Truman ordered that “the Bug” be released.

In January 1977, Stoppelli was rounded up with Genovese capo James Napoli and held on charges of conspiracy and promoting gambling. The ring was busted when an undercover officer using the name “Joseph DeVito” infiltrated the group in 1974 and worked for two years as a “pickup man” (someone who collects and delivers gambling records for “district managers” or “controllers”). Stoppelli and Napoli were said to be partners in the multimillion-dollar operation.

Stoppelli died of natural causes at eighty-six years old, ending a sixty-plus-year career in crime.

S

TROLLO,

A

NTHONY

177 Thompson Street, 1920

Alias: Tony Bender

Born: June 18, 1899, New York City

Died: April 8, 1962(?), Fort Lee, New Jersey (disappeared)

Association: Genovese crime family acting boss

Anthony Strollo was born to forty-four-year-old Leone Strollo and thirty-two-year-old Giovannina “Jennie” Nigro, Calabrian immigrants who arrived in New York City in the late 1880s. He grew up at this address on the outskirts of Little Italy (coincidentally, the same building where Vincent Gigante was born in 1928), where his father owned a local candy store.

Strollo’s arrest record dates back to 1926, when the young gangster lent his criminal talents to the Masseria crime family before wisely defecting, along with Charlie Luciano, Vito Genovese and others, to Salvatore Maranzano’s Brooklyn-based clan in 1930 during the Castellammarese War.

When the Mafia was restructured in 1931, Strollo’s allegiances paid off, and he was recruited into the Luciano (Genovese) crime family, where he took over operations of the organization’s Little Italy crew by 1935. Strollo was said to be one of the few good friends that Vito Genovese had. The pair participated in a double wedding ceremony in March 1934 and stayed close for the next couple of decades.

By the 1950s, Strollo was allegedly controlling much of the Genovese family nightclub, waterfront and policy racket operations, which extended into northern New Jersey. At about midnight on March 14, 1952, Jersey City mayor John V. Kenny was observed meeting with Strollo for ninety-seven minutes at the Warwick Hotel (65 West Fifty-fourth Street), for which the politician was questioned for three hours by the State Crime Commission on May 27. Mayor Kenny first denied everything but eventually admitted to meeting with the known mobster in “an attempt to end waterfront unrest.”

120

It was speculated that the New York mob’s infiltration of the docks in Mayor Kenney’s district upset the politico’s New Jersey mob associates, who put pressure on him to do something about the situation. When Strollo offered to “help,” a meeting was set up by a mutual associate, entertainer Phil Regan, who hosted the event at his Midtown hotel suite.

In the end, Mayor Kenny caved in to Strollo, action that apparently did not please his constituents. Anthony Strollo’s brother, Dominick, who helped oversee the waterfront operations, was found beaten and unconscious on a Jersey City pier on July 5.

On April 1, 1953, it was uncovered that fifty-six longshoreman, who got their jobs because of Mayor Kenny’s influence, had criminal records. Most of them worked at the Army Claremont Terminal—which the military abandoned in November 1952 because racketeering made it too costly to operate—the same location where Dominick Strollo was found beaten.

According to Joe Valachi, Anthony Strollo was his first boss when initiated into the Luciano family in the early 1930s. Valachi also testified that Vito Genovese was behind Strollo’s 1962 disappearance. In a televised 1963 hearing, Valachi told the world that upon hearing news reports of Strollo’s disappearance, Genovese stated that it was “the best thing that should happen.”

121

In 1972, FBI surveillance picked up a conversation in which Jersey mobster Ruggiero “Richie the Boot” Boiardo claimed responsibility for the murder of Strollo, though feds believed it might have been an intentional ploy to mislead them.

Many insiders believe Genovese had longtime friend Strollo murdered because he disobeyed orders to not sell drugs. Others have since claimed that the mobster faked his own death and lived out the rest of his life in Florida. The world may never know. The body of Anthony Strollo has never been found, and the disappearance remains officially unsolved.

T

OURINE

, C

HARLES

, S

R

.

40 Central Park South, 1940s–1970s

Alias: Charlie the Blade

Born: March 26, 1906, New Jersey

Died: May 28, 1980, Miami, Florida

Association: Luciano/Genovese crime family capo

This Jersey-born mob heavyweight was a big-time gambler with interests in New York, New Jersey, Las Vegas, Miami and Cuba. He was said to have been considered for the boss position when Vito Genovese passed away in 1969; however, sources say that the fact that he was illiterate prevented the move.

Born to two recent Italian immigrants, Frank, a retail clerk, and mother Mary, young Charles Tourine grew up at 68 Main Street in Matawan, New Jersey. Tourine began his mob career working with a Jersey-based Luciano/Genovese crew led by Richard Bioardo.

On December 15, 1944, thirteen members of an alcohol-manufacturing ring were sentenced to a total of thirty-five years in prison after pleading guilty to running four illegal alcohol stills in Union Township, New Jersey. Tourine, who was living at the swanky San Moritz Hotel at 40 Central Park West, allegedly headed the operation and was sentenced to five years behind bars.

In 1951, Tourine was included on a government list of 126 notorious underworld figures whose income taxes were being investigated.

122

On April 29, 1968, New York customs agents uncovered a bundle of illegal pornographic magazines in a crate shipped from Copenhagen. The contraband was eventually traced to Tourine, who was indicted on May 21, 1969, for conspiring to bribe customs agents in order to smuggle $250,000 worth of adult literature into the country. During the October 1970 trial, all witnesses refused to answer questions, and no convictions were awarded.

In January 1970, while investigating the relationship between the motion picture industry and organized crime, the Joint Legislative Committee on Crime played a tape of a conversation between Tourine and a man named Kirk Kerkorian, controlling stockholder of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios and founding partner of the original MGM Hotel in Las Vegas. In the 1961 recording, Tourine explained to Kirkorian the best way to send him $21,300. A check was to be given to movie star George Raft—the native New York actor famous for playing mobsters on the big screen—who was to cash the check and deliver it to Tourine. Of course, all parties refused to answer questions, and no explanation was ever made as to what the $21,300 was for.

In November 1970, Tourine was spotted having lunch three times with Frank Costello at Gatsby’s Restaurant, at 20 East Forty-first Street. These meetings, held just months after the death of Vito Genovese, led authorities to speculate that Costello was coaxed out of retirement to help sort out the family’s transition.

The semi-retired Charles Tourine had moved to Miami, Florida, by 1976 but never turned down a good business opportunity. In August of that year, Tourine pleaded innocent to federal charges stemming from a scheme to establish a gambling and prostitution ring along the new Alaskan pipeline. After a lengthy trial, Tourine and five co-conspirators were acquitted by October 1977.

On February 26, 1977, Tourine was one of five high-level mobsters, including Meyer Lansky, to be subpoenaed by the Dade County state attorney’s office to answer questions about the May 1976 murder of a former Mafioso named John Rosselli, whose body was found stuffed in an oil drum in Biscayne Bay, Florida. Rosselli had testified before several grand juries and committees about an alleged plot by the CIA to kill Fidel Castro by recruiting the Mafia.

Tourine’s son, Charles Jr. (later known as Charles Del Monico), followed in his father’s footsteps and racked up quite a criminal career himself. He was also born in New Jersey but was living at 420 East Sixty-fourth Street by the 1960s.

T

RAMAGLINO

, V

ICTOR

302 East Twelfth Street, 1912; 214 First Avenue, 1932

Alias: Victor Romano

Born: March 19, 1912, New York City (b. Tramaglino, Vittorio)

Died: May 26, 1980

Association: Genovese crime family soldier

Born to Lorenzo and Amolia Tramaglino in an apartment above John’s Restaurant at 302 East Twelfth Street, the future Genovese soldier attended local PS 19 (the same school Charlie Luciano attended), where the bright student excelled academically and was allowed to skip two grades.

Lorenzo Tramaglino, an insurance salesman, fought hard to keep his eight sons out of trouble; one time he actually turned one of Victor’s brothers in to police when he was caught gambling in the street. Despite Lorenzo’s efforts, the influence of older neighborhood hoodlums like Joseph Biondo set Victor up for a life of crime. In fact, his neighbors at the time read like a who’s who of aspiring mobsters: Joe N. Gallo (future Gambino consigliere), George “Lefty “Rizzo, Billy and Tony Esposito, Thomas “Bullets” Licatta (Tramaglino’s future boss) and Matteo “Marty” DeLorenzo, the future Genovese capo who made headlines in the 1970s for his role in the Vatican Connection.

Victor Tamaglino’s first arrest came at age eleven, when he was collared with two other kids for a petty theft five days before Christmas 1923. They were caught attempting to steal a toy from a display rack at a local shop. Spending most of his childhood in and out of reform schools and detention centers for truancy, Tramaglino formed a lifelong relationship at a young age with many of the men he would work with throughout his life.

Matteo DeLorenzo was with Tramaglino during an early arrest on March 20, 1932. In that incident, the pair attempted to rob a Greek bookmaker named Sempros, who was making his collection rounds on East Fourteenth Street. A man called “Pepe” was recruited as a lookout.

Tramaglino followed the bookie into an East Fourteenth Street apartment building hallway while DeLorenzo stood guard across the street. When a suspicious beat cop happened upon the scene, Pepe, who was a few doors away, fled without warning his accomplices.

The officer followed Tramaglino into the building, gun drawn. The armed gangster swung around and came face to face with the barrel of a police revolver. In the heat of the moment, the two exchanged shots, and Tramaglino was struck in the side of his head and shoulder. When he tried to run, a second officer shot him in the knee.

DeLorenzo was picked up across the street, and Pepe got away. As was customary of the “code,” the lowest man on the totem pole was usually required to take the fall, and Tramaglino faced twenty-five years for attempted murder alone, plus additional gun charges. DeLorenzo walked away with a two-year sentence.

Instead of facing a jury, Tramaglino opted for a twenty-year plea deal and was sent to Sing Sing. As chance would have it, while Tramaglino was serving time, Pepe showed up in the same prison on an unrelated charge. He was stabbed to death soon after being admitted. No charges were ever filed, but authorities suspected Tramaglino and transferred him to Attica, where he finished his sentence.

By the time Tramaglino was released in 1946, DeLorenzo was already made, and he helped Tramaglino join the Mafia. He didn’t forget that Tramaglino took the rap in 1932 and served his twenty years quietly (he didn’t rat anybody out—a sure sign of loyalty).

Tramaglino was recruited into the Genovese organization that year, and his first boss was Thomas “Bullets” Licatta, whose crew operated out of the same Lower East Side neighborhood—the East Village—where they grew up. Licatta and Tramaglino were close—“Bullets” was even best man at Tramaglino’s wedding.

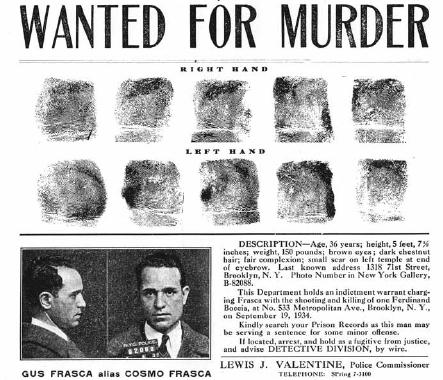

When Thomas Licatta died in 1952, Cosmo “Gus” Frasca took over the Genovese family’s East Village crew. From that point on, Tramaglino stayed out of narcotics and focused on loan-sharking and gambling. By the 1960s, he was running some of the biggest games in the city, essentially floating underground casinos in makeshift apartments, hotel rooms and café cellars.

On February 5, 1963, the FBI released an internal memo that listed 347 suspected Mafia members operating in New York City, requesting that individual investigations be conducted on each. Victor Tramaglino and his brother Julio were listed alongside fellow mobsters Frank Mari, Ralph Polizzano and Carmine “Sonny Pinto” Di Biase, a close friend of Victor Tramaglino and future accused assassin of “Crazy Joe” Gallo.