Manhattan Mafia Guide (19 page)

Read Manhattan Mafia Guide Online

Authors: Eric Ferrara

Mirra and his thirteen codefendants remained behind bars until the retrial in April 1962. This trial turned out to be more colorful than the first and was beset by several sensational outbursts and interruptions. In May 1962, two codefendants, Carmine and Salvatore Panico, attempted to intimidate the jury by standing up from their chairs and shouting at them; Salvatore climbed into the jury box and began pushing around a jurist. The Panico brothers were gagged and chained to their chairs for over a week after the incident.

One week later, on June 4, Mirra stood up from the witness stand while being cross-examined and, without a word, picked up the fifteen-pound wooden chair he was sitting on and hurled it at assistant U.S. attorney John Rosner. Mirra was tackled by four officers and bound by shackles. On June 8, the trial was temporarily adjourned when Salvatore Panico slit his wrists in a Federal House of Detention cell (427 West Street).

Mirra, Galante, Di Pietro, Ormento and nine others were sentenced on July 10, 1962, to a total of 276 years in prison. Mirra, Galante and Di Pietro received 20-year sentences, while ringleader Ormento was hit the hardest, with a hefty 40-year sentence. Mirra, Galante and six others were awarded additional sentences of up to eighteen months for contempt of court. Appeals by Mirra in 1963 and 1967 were unsuccessful.

Anthony Mirra was back on the street by the early ’70s. Spending over a decade behind bars did little to dissuade the ex-con from engaging in organized crime, and he began a large-scale shakedown racket of Manhattan nightclubs, bars and restaurants. Working under Bonanno capo Michael Zaffarano, Mirra became involved in the adult film industry (behind the scenes) and provided muscle in the Bonanno-controlled porn theaters of Times Square.

In October 1974, a Bangladeshi immigrant and restaurateur named Shamsher Wadud provided the public a firsthand account of how a Mafia shakedown is carried out, via an article in the

New York Times

.

102

Wadud opened a discotheque called Nirvana Culture at 151 East Fiftieth Street and claimed that within two weeks three men walked in and offered to help increase business. A man introduced as Anthony Graziano (a Lucchese family member) told Wadud, “You’ve got a terrific place here…But you should be doing a lot more business than this. Give us a call. We can do a lot to help you.”

Wadud did not call, and two days later over a dozen men entered the club and began to harass the patrons. An associate of Graziano told Wadud, “This kind of problem can happen all the time. When you wind up in the hospital, you’ll wish you had called us.”

The very next day, Wadud met with Graziano and company, who offered to increase his business from $7,000 to $25,000 a week for 10 percent of the profits. He explained to the naïve club owner, “This is not a shakedown, just give us a chance.” Wadud agreed, and sure enough patronage increased almost immediately. Only there was a problem: the crowd was composed of mob associates who ran up large tabs, refused to pay their bills, got into fights and drove away regular customers.

As (bad) luck would have it, Wadud was soon approached by Anthony Mirra, who demanded a whopping 50 percent of profits from the discotheque. Wadud went to his new partner, Anthony Graziano, who essentially offered to keep Mirra off his back for 25 percent of the club’s profits. Instead of dealing with the headache, Wadud closed Nirvana within a few days and went into hiding. Such was the cost of doing business in 1970s New York City.

In March 1977, Anthony Mirra met a man who introduced himself as a jewel thief named Donnie Brasco, unknowingly setting in motion the near collapse of the Bonanno crime family. Thanks to Hollywood, the story of undercover FBI special agent Joseph Pistone, aka Donnie Brasco, has been well told. But unfortunately for Mirra, he would not live to see the movie.

On February 18, 1982, a woman complained to police that a gray Volvo was blocking the garage entrance to Independence Plaza, a residential apartment building at 80 North Moore Street. Upon investigation, the engine was still running, and Mirra’s body was found slumped over with four bullet wounds to the back of his head and $10,000 in his pocket.

Mirra’s murder is said to have been orchestrated by his own uncle, Alfred Embarrato, and carried out by cousins Joey D’Amico and Richie Cantarella on the orders of Bonanno boss Joe Massino. It was retaliation for Mirra allowing the FBI infiltration.

M

ORELLO

, G

IUSEPPE

178 Christie Street, 1903; 630 East 138

th

Street, 1909; 207 East 107

th

Street, 1910

Alias: Piddu, Peter Morello, Clutch Hand

Born: May 2, 1867, Corleone, Sicily

Died: August 15, 1930, New York City

Association: Founder of the Morello gang

At the turn of the century, Morello organized a band of Sicilian extortionists and counterfeiters in New York City, unknowingly planting the seeds of what would become known as the “First Family of the American Mafia,” an organization the FBI would christen the “Genovese crime family” in the 1960s.

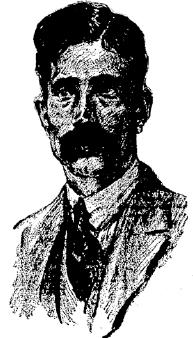

Giuseppe Morello sketch.

“My Ten Biggest Man Hunts” article by William J. Flynn, former chief of the United States Secret Service. Published in the

New York Herald,

January 29, 1922

.

In 1872, when Morello was a child back in Sicily, his father, Cologero Morello, died, leaving his son in the care of young mother Angela Piazza Morello. In 1876, Angela remarried, to a man named Bernardo “Beney” Terranova (July 6, 1847–May 28, 1913), who had three sons of his own: Ciro, Vincenzo and Nicolas.

When the Morello-Terranova stepbrothers became teenagers, Bernardo, a member of the Sicilian Fratelanza himself, encouraged them to join the local Cosca before moving the family to the United States in 1893.

The Terranovas initially settled on the Lower East Side,

103

before family members branched out into East Harlem and the Bronx. The brothers tried their hand at several legitimate occupations and business ventures but ultimately turned their attention to counterfeiting. Yes, counterfeiting was a primary racket that led to the establishment of La Cosa Nostra in this country—perhaps not as sexy as Hollywood would like us to believe.

Giuseppe Morello took the reins as ringleader and developed great influence in the Corleone criminal communities of New York City. By the turn of the century, Morello had joined forces with Ignazio Lupo,

104

who had arrived in New York by 1899 to escape murder charges back in Sicily. Lupo married into the family on December 22, 1904, by taking Salvatrese Dora Terranova, Morello’s stepsister, as his bride.

The core of Morello’s small clan was Corleonisi, but other Italians were also attracted to the enigmatic leader—as were non-Italian criminals, perhaps impressed with his Mafia pedigree. Without the help of established criminal networks in this city, the Morellos may not have made the impact that they did.

On the morning of June 11, 1900, Giuseppe Morello and associate Colagero Meggiore were arrested and held on $5,000 bail, suspected by the Secret Service of producing counterfeit five-dollar bills. Four Irishmen, named Whalen, Green, Gleason and Thompson, were also picked up in the sweep, on suspicion of purchasing the crudely made currency for two dollars each and then distributing it in non-Italian Brooklyn and Queens communities. Morello, who gave his address as 337 East 106

th

Street, was held for about a week before being released due to lack of evidence.

The arrest did little to dissuade Morello from expanding his criminal enterprises over the next decade; however, the outfit would face a few obstacles along the way. In the fall of 1902, five members of Morello’s ring were incarcerated for manufacturing counterfeit silver coins in a Hackensack, New Jersey home. Arrested during the sting was visiting Sicilian Mafia boss Vito Cascioferro, who gave his address as 361 First Avenue—he was ultimately released.

The fact that Cascioferro spent time in New York City with the Morello gang at the turn of the century does not mean that there was an official connection between the Sicilian and American Mafias, as is often implied. In fact, there is not much evidence to support that theory. Don Vito did work closely with the Morellos during his almost three years in America, but his activities in the United States are not known to have been on behalf of any Sicilian Mafia organization.

Giuseppe Morello was suspected in the July 1902 Brooklyn murder of Giuseppe Catania, thought to have had a falling out with the Morellos, but no charges were ever brought against the gang leader. Later that year, the small gang would take another hit when three of its members were again arrested in December for passing illegal currency through a Morristown, New Jersey bank.

After the 1902 counterfeiting arrests, the U.S. Secret Service kept a close eye on the Morellos. The homes and businesses of several gang members were under constant surveillance, especially Morello’s “saloon and spaghetti kitchen” at 8 Prince Street, which served as the gang’s headquarters.

That block of Prince Street between Bowery and Elizabeth would eventually become known to locals and authorities as “Black Hand Block.” It was an epicenter of early Mafia activities in this city for close to two decades. The

New York Times

reported in 1911, “When detectives have wanted to get wind of an Italian criminal, they began their search at that address [8 Prince Street].”

105

It was at 8 Prince Street where Vito Cascioferro held meetings with the Morellos during his time in America. It was also at the center of a sensational 1903 murder investigation, after the body of a Buffalo, New York man named Benedetto Madonia was found stuffed inside a sugar barrel on the sidewalk in front of 743 East Eleventh Street on the morning of Tuesday, April 14. (See Madonia, Benedetto, “Gangland Hits” chapter.)

After the “Barrel Murder,” Giuseppe Morello moved the base of his operations from the Lower East to the Upper East Side. The gang leader set up a primitive printing press in an apartment at 329 East 106

th

Street, where he produced modest quantities of barely passable paper money. Morello then sold these fake bills to Sicilian and Irish launderers (shovers) who purchased them at about forty cents on the dollar, redistributing them to saloons and gambling parlors across the five boroughs.

8 Prince Street today.

Courtesy of Shirley Dluginski

.

Beyond counterfeiting, Morello expanded into real estate and construction by establishing the Ignatz Florio Co-Operative Association Among Corleonesi in 1902. Company shares were offered to (and/or forced on) members of the Italian community, and Morello was soon handling property deals worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The Morellos flourished in the real estate market for a few years, both legitimately and otherwise, though the company folded by the end of the decade. By this time, the family’s operations had branched out to Italian communities in major cities across the United States, like New Orleans, Buffalo, Philadelphia and Boston. They had accumulated enough money and power to pay off corrupt police and sway favor from local politicos. It appeared as though the Morellos were almost untouchable; however, the law finally caught up with the outfit by 1909.

In the summer of that year, Secret Service detectives secured a tenement apartment across the street from a Morello gang–run grocery at 235 East Ninety-seventh Street, which they suspected was operating as a front for the ring’s counterfeiting racket. Throughout the fall of 1909, authorities recorded all the goings-on at that location and others and noticed a steady supply of inks and paper being shipped to a farm in Highland, New York, among other suspicious activities.