Manhattan Mafia Guide (15 page)

Read Manhattan Mafia Guide Online

Authors: Eric Ferrara

In a 1920 federal census, Joseph Lanza is listed as a driver at the (Fulton) “fish market.” By 1930, father Salvatore was out of the picture, and Joseph was listed as “head” of the family, living with his new wife, Rose; his mother, Carmella; and seven siblings at 102 Madison Street and working as a “delegate” for the “fish union.”

In August 1924, young Joseph and a fireman named William Seavers saved two men from drowning when a group of four drunken workers fell off the pier behind the fish market. Quick-thinking Lanza swam to the floundering drunks and held two of them above water. Seavers threw Lanza a buoy and a rope and then successfully plucked the men out of the rough waters. The other two men did not survive.

87

In 1919, nineteen-year-old Lanza got his feet wet in union racketeering at the Fulton Fish Market when he organized and became business agent of a United Seafood Workers local,

88

a charter of the American Federation of Labor. Shortly after, the Fulton Market Watchmen and Patrol Association was established, offering merchants “protection” from vandalism of their property or stock. Over the next decade, Lanza’s influence at the market grew, and virtually every single union worker, wholesaler, retailer, transporter and commercial business associated with the fish market would be subject to a variety of extortion rackets.

Fulton Market, 1939. New York World-Telegram

and the

Sun

Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress). Photo by Edward Lynch

.

For example, merchants were forced to purchase fish at marked-up prices from “approved” shipments and pay a $3-a-week tax to protect their personal autos parked on local streets from damage. Ship captains were required to pay $10 for every docking. Those who did not cooperate could not unload their boats and were refused ice to keep their inventories fresh, often forcing crews to dump thousands of pounds of spoiled fish into the ocean at the end of the day. Even local hotels and restaurants had to pay up to $1,000 a year for the “privilege” of purchasing fresh fish from the market. Victims soon realized it was simply cheaper to pay Lanza than to go through the legal system.

The power Lanza wielded over the industry came to the public’s attention during a 1931 investigation of New York district attorney Thomas C.T. Crain, who was accused of failing to prosecute the racketeers of the Fulton Fish Market, citing the fact that out of 150 cases, only 3 led to indictments.

89

At least three days of testimony centered on the United Seafood Workers, as several witnesses (as many as fifteen in one day) pointed to Lanza as the man behind the fish market extortion rackets, claiming to have paid up to $6,000 a year in “tributes” for the right to do business at the market over a ten-year period.

By the end of 1931, a network of truck drivers and fishermen from Connecticut and Rhode Island united to create the Southern New England Fisherman’s Association in an effort to breach the mob’s control of the Fulton Fish Market. Among several complaints was the allegation of being discriminated against for being from out of state. The association complained that out-of-town trucks could not unload without paying tribute to a New York union or hiring a union member “or else.”

90

Some of the mob’s retaliations were subtle on the surface but could cost out-of-state companies thousands of dollars a day. For example, despite lining up at the break of dawn, non–New York truckers had to wait and then fight for space on the loading docks toward the end of the day, when the value of their delivery was at its lowest.

Corruption charges against District Attorney Crain were eventually dismissed, but the experience seems to have motivated the nearly fallen prosecutor to take up a crusade against organized crime at the Fulton Fish Market, at least for the public’s sake. In May 1933, he opened a new investigation into Lanza and his union rackets. On June 5, 1933, Lanza and fifty-three associates were indicted on various charges ranging from coercion to extortion. In October 1934, Lanza was again acquitted of all charges.

Another investigation of the market’s managing practices in 1935 led to the indictments of eighty-two racketeers and a two-year prison term for Lanza. He remained on the USW payroll for a year while behind bars, until retiring from his position on December 31, 1937.

When released from a Michigan federal penitentiary, Lanza again attempted to gain control of his old union. The American Federation of Labor threatened to dissolve the USW charter if Lanza was reelected to his old position, citing a lengthy criminal record of seventeen arrests in as many years. In July 1940, Lanza was voted in regardless of the threat, and the AFL made good on its promise and dropped the USW. The troubled ex-con was forced to retire in August in order for the union to survive.

Despite the lack of an official title, Lanza remained the undisputed king of one of the largest wholesale markets in America. It is said that he worked closely with U.S. Navy intelligence during World War II, offering his intimate knowledge of waterfront activities and network of dockworkers, fisherman, boat crews and ship captains to the war effort.

By the end of the war, Lanza found himself incarcerated again on a seven- to ten-year extortion conviction. He was so powerful by then that it is said he was paid kickbacks from Fulton Fish Market activities throughout his entire prison sentence.

Lanza was arrested one more time in 1957 on parole violations for gambling and “associating with notorious criminals and known racketeers,”

91

but his nearly half century of control of the Fulton Fish Market lasted until October 11, 1968, when he passed away at sixty-four.

L

ISI

, A

NTHONY

97 Madison Street, 1927; 154 East Broadway, 1950s; 1 Essex Street, 1966

Alias: Anthony Leis

Born: July 11, 1911, Giarre, Sicily (b. Lisi, Gaetano)

Died: 1971, New York City

Association: Bonanno crime family

92

Father Sebastian Lisi and mother Sebartiana “Neli” Grno

93

arrived in New York City from Palermo with babies Gaetano (Anthony) and Isiidora (Dorothy) on the SS

Italia

on December 30, 1912. Here, they settled at 97 Madison Street in the mob-heavy Fourth Ward district of the Lower East Side, where Sebastian went to work as a bottler at a 139 Madison Street factory.

Anthony Lisi’s first arrest came in 1932, and within two decades, he had racked up multiple charges for everything from weapons possession, robbery and disorderly conduct to grand larceny, federal narcotics violations and murder. By the 1950s, he was working with the Bonannos and had close ties to the Montreal Controni crime organization. He also held interest in several legitimate businesses, like the CIA and Holiday Inn bars.

97 Madison Street today.

Courtesy of Sachiko Akama

.

In the 1960s, it is said that Lisi stayed loyal to boss Joe Bonanno during the Banana War, which divided the family for most of the decade. In July 1966, Lisi and three other Bonannos were sentenced to thirty days in jail and $250 in fines for contempt of court, a term Lisi served in October of that year. He was convicted of contempt again in 1969 for refusing to testify before a grand jury inquiry into organized crime.

In February 1971, fifty-four members of an alleged heroin ring, including sixty-year-old Lisi, were swept up by authorities during a simultaneous raid in four cities; however, Lisi was never sentenced. He passed away before the trial was complete.

L

UCIANO

, C

HARLIE

265 East Tenth Street, 1910s–1930s; 160 Central Park South (Essex House Hotel), 1930s; 106 Central Park South (Barbizon-Plaza Hotel), 1930s; 301 Park Avenue, Thirty-ninth Floor (Waldorf Hotel), 1930s

Alias: Salvatore from Fourteenth Street, Charlie Lucky, Lucky, Charles Ross, Charles Reid, Charles Lane

Born: November 24, 1897, Lercara Friddi, Sicily (b. Lucania, Salvatore)

Died: January 26, 1962, Naples, Italy

Association: Luciano/Genovese crime family boss

“Charlie Lucky,” as he liked to be called, was the legendary mobster whom many claim to be the most important in American history. That title has been challenged over time, but there is no denying the vice kingpin’s legacy and influence during the Mafia’s formative years.

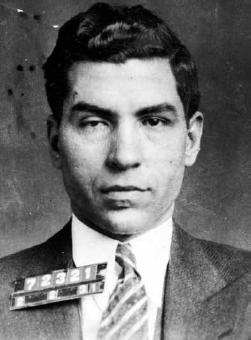

Charlie “Lucky” Luciano mug shot, 1931.

Luciano’s story has been told with varying nuances in countless books, articles and movies for over a half century; however, rarely does the author tell you that much of what we know about this iconic mobster is essentially entirely speculative. Most of the familiar narrative was pulled together from the testimony of Mafia turncoat Joe Valachi and what was purported to be Luciano’s own personal memoirs, the 1974 book

The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano

(which itself was pieced together from Valachi testimony according to the FBI, as discussed later in this chapter). Almost every word that has been written about Charlie Lucky since then has pretty much been inspired by these same sources and embellished to fit whatever narrative the storyteller is presenting.

Sicilian-born to parents Antonio and Rosalia Lucania, Luciano arrived in New York City in October 1907 at ten years old, settling with his family in the working-class district of Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The future gangster icon had no Mafia ties when he arrived in this country.

94

His father was said to be a hardworking, law-abiding sulfur miner from a rural Sicilian town who tirelessly saved for years to give his family a better life in America.

As Luciano would later recall:

We had a calendar that come from the steamship company in Palermo, which was where you got on the boat. My old man used to get a new one every year and hang it up on the wall, and my mother used to cross herself every time she walked past it. Sometimes we even went without enough to eat, because every cent my old man could lay his hands on would go into a big bottle he kept under his bed.

95

In America, young Luciano attended Public School 19 (344 East Fourteenth Street, now the site of a YWCA) until about 1911, when he dropped out at age fourteen and secured employment at a local factory for a few months before deciding that holding down a legitimate job was for “crumbs.”

As the story goes, Luciano’s volatile relationship with his father had all but deteriorated during this time period. The future vice king had by that time already been influenced by the street and was flirting with a life of crime, spending time in juvenile detention and getting into trouble for various petty crimes like shoplifting. The tipping point was said to have come when Antonio discovered that his fourteen-year-old son was in possession of a revolver. The altercation was so intense that Luciano fled the family apartment at 265 East Tenth Street, only to stealthily return on occasion during the day for a home-cooked meal from Mom.