Making Our Democracy Work (35 page)

Read Making Our Democracy Work Online

Authors: Stephen Breyer

But a broader question still remains to be answered. As I said at the outset, when Benjamin Franklin was asked what kind of government the Constitutional Convention had created, his famous reply, “A republic, Madam, if you can keep it,” challenges us to maintain the workable democratic Constitution that we have inherited. In a democracy, enduring institutions depend upon the enduring support of ordinary citizens. And citizens are more likely to support those institutions they understand. Thomas Jefferson pointed this out. Even under the “best forms” of government, he said, “those entrusted with power have, in

time, … perverted it into tyranny”; the “most effectual means of preventing this” is “to illuminate … the minds of the people at large.”

2

So the broader question is, how do we “illuminate” those minds? How do we explain to the ordinary American why and how he or she should try to maintain a strong judiciary? The need is great. As we have seen, judicial independence forms one necessary part of a judicial institution that can help make the Constitution’s promises effective. And, as Justice David Souter has pointed out, a

populace that has no inkling that the judicial branch has the job of policing the limitations of power within the constitutional scheme, and no understanding that judges are charged with making good on constitutional guarantees even to the most unpopular people in society, that populace will hardly find much intuitive sense when someone trumpets judicial independence or decries calls to impeach judges who stand up for individual rights against the popular will.

3

A public that does not understand the judiciary, its role in protecting the Constitution, and the related need for judicial independence may act in ways that weaken the institution. Where judicial elections take place, for example, as they do in many states, the electorate can vote against candidates who reach unpopular decisions, they can authorize litigants to contribute millions of dollars to judicial candidates, they can enhance the electoral importance of individual cases by limiting the length of judicial terms of office, and they can support ballot initiatives such as South Dakota’s “jail for judges” who “wrongly” decide cases. Where judges are not elected, as in the federal system, voters can still communicate to legislators that when they help select judges, politics, not law, is what matters.

4

Indeed, as part of a 2000 survey asking whether judges decide cases on political or legal grounds, about two-thirds of respondents answered “legal”; five years later this number had dropped to about half.

5

But explanation and widespread education are not easy to accomplish. People are busy going about their daily lives. And relevant concepts and reasons are not always easy to understand. Judicial

independence, for example, is essentially a state of mind. Judicial independence was not present when a Soviet party boss would telephone a judge to tell him how to decide a case—on the unspoken penalty of the judge’s being deprived of a decent apartment or good schooling for his children. How can we explain the isolation of a judge confronted with the task of independently deciding an unusually difficult case? Can we explain this quickly to our fellow citizens who live busy, pressured lives?

It takes time and continuous effort to communicate the nature and importance of our government institutions. Support for the judicial institution rests upon teaching in an organized way to generations of students about our history and our government. It grows out of knowledge of our Revolution, our founding documents, the Civil War, and eighty years of legal segregation. It rests upon an understanding of our Constitution, of how government works in practice, and of the importance of the students’ own eventual participation to the Court’s continued effectiveness.

There is cause for concern about the health of this kind of education. Compared with a generation ago, there seem to be fewer classes in civics and government, fewer town meetings where (in Justice Souter’s words) “my concept of fundamental fairness began to form.” Only twenty-nine states now require the teaching of civics or government as part of their public school curriculum. This decline may help explain the dismal statistics: that a vast majority of eighth graders are not proficient in civics; only one-third of all Americans can name the three branches of government (two-thirds can name a television judge on

American Idol);

only one-third of eighth graders can describe the historical purpose of the Declaration of Independence; and three-quarters of our population does not understand the difference between a judge and a legislator.

Still, pessimism is not the complete order of the day. Private citizens, foundations, corporate officials, legislative committees, leaders from across the political spectrum, and retired Supreme Court justices are hard at work developing teaching materials and encouraging the teaching of civics. No one has worked harder than Justice O’Connor to explain to the public the need for civics education, including education about how our judicial institutions work.

Lawyers, bar associations, and judges can do the same. They can speak to students about the law; they can arrange for visits to the courts; they can help the schools develop teaching materials. Lawyers and judges can meet with local groups and explain what law is, what our legal system is like, what courts do, how the legal system and the courts affect the lives of ordinary citizens. Their presence transmits a simple message: we work with the law and with the Constitution. Our democratic Constitution assumes a public that participates in the government that it creates. It also assumes a public that understands how government works. Without this public understanding, the judiciary cannot independently enforce our Constitution’s liberty-protecting limits.

The stories this book sets forth are told from the point of view of one judge. I have drawn my own lessons from them. I hope they lead others to study the stories and ponder their lessons about our constitutional history. Then they too will be better able to help make our democracy work. I hope so.

That is why I have written this book.

Images

T

HIS BOOK DISCUSSES LEGAL CASES AND PRINCIPLES AT

length, but it is important to remember that these cases were decided by, and these principles have a profound effect on, human beings. My hope is that the following paintings and photographs will help the reader to make this connection—to recognize that behind each of the famous cases I have described are real issues that have confronted real people.

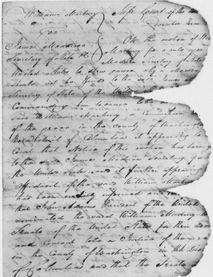

First, I have included a portrait of Chief Justice John Marshall, who did so much to shape our understanding of the Constitution, along with a copy of the order served on James Madison asking him to explain why he never delivered William Marbury his judicial commission. Of course, the controversy over Marbury’s commission led directly to Chief Justice Marshall’s decision in

Marbury v. Madison

, which established the Court’s authority to engage in judicial review.

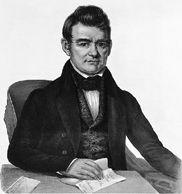

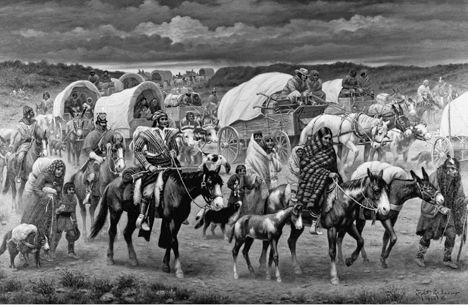

Second is a portrait of Chief John Ross, the Cherokee leader who fought so valiantly for his land, along with a painting of the Cherokee migration along the Trail of Tears, which the tribe traveled to Oklahoma after its eviction from Georgia.

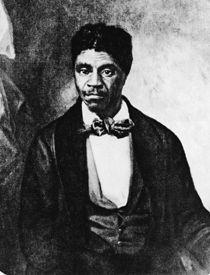

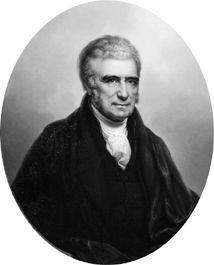

Third, a well-known portrait of Dred Scott still leads us to think of his fortitude and humanity as he brought about a case the very vices of which helped awaken the nation to the need for slavery’s abolition. And portraits of Chief Justice Roger Taney and Justice Benjamin Curtis represent the opposite sides of a deep division that would split not only the

Court in

Dred Scott v. Sanford

, but also the nation four years later in the Civil War.

Fourth, two photographs of the Little Rock integration tell us much without words. The first shows the failed efforts of one of the nine students to integrate the school in the face of strong opposition from those in the crowd. The second shows the world that, with the help of the 101st Airborne Division, the rule of law would carry the day. And a picture of the tombstone of Chief Ross’s wife, who died on the Trail of Tears, reminds us that she, a symbol of a president’s denial of the rule of law, lies only a mile from Little Rock High School, the scene of one of the law’s greatest triumphs.

Fifth, I have included pictures of a sign directing individuals to World War II Japanese internment camps, and of a camp itself, providing a glimpse of the conditions in which these American citizens lived.

The final is a photograph of Thurgood Marshall and members of the Little Rock Nine sitting on the Supreme Court’s front steps. This image suggests the distance our nation has traveled in making Chief Justice Marshall’s vision of America, as set forth in

Marbury

, a practical reality.

This painting, which hangs in the United States Supreme Court, depicts John Marshall, the great chief justice who wrote the Court’s opinion in

Marbury v. Madison

.

(

Rembrandt Peale, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

)

Before deciding

Marbury v. Madison

, the Court issued this show-cause order, in effect asking Secretary of State James Madison to respond to Marbury’s claim. Madison did not respond.

(

National Archives

)

Chief John Ross led the Cherokee Nation. He strongly opposed Georgia’s efforts to seize the Cherokees’ territory, and he encouraged Supreme Court litigation on the matter.

(

Library of Congress

)

After the ultimate failure of the tribe’s efforts to keep their land, they were forced to immigrate to the West. This painting depicts their involuntary journey along the Trail of Tears.

(

The Granger Collection, New York

)