Making Our Democracy Work (36 page)

Read Making Our Democracy Work Online

Authors: Stephen Breyer

Dred Scott, who invoked the law in order to escape the bonds of slavery, became the subject of a Supreme Court case, now viewed as one of the Court’s worst decisions.

(

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

)

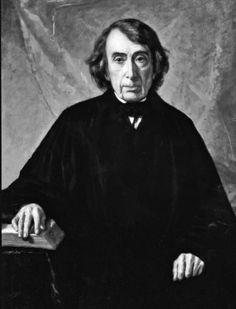

A native of Maryland and once Andrew Jackson’s attorney general, Roger Taney wrote the Court’s

Dred Scott

decision.

(

George Peter Alexander Healy, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

)

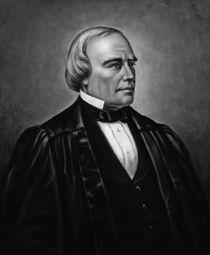

A native of Massachusetts, Justice Benjamin Curtis wrote the principal dissenting opinion in

Dred Scott

.

(

Gregory Stapko, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

)

This famous photograph shows Elizabeth Eckford unsuccessfully attempting to enter Little Rock Central High School.

(

Will Counts Collection: Indiana University Archives

)

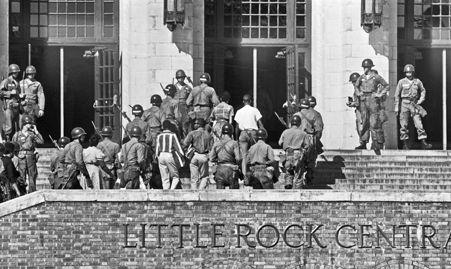

Above:

Members of the 101st Airborne Division escorting the Little Rock Nine into Central High School.

(

Bettmann/Corbis

)

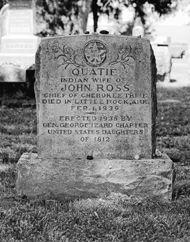

Right:

Quatie Ross, the wife of Chief John Ross, lies buried where she died along the Trail of Tears. The trail symbolizes a defeat for the rule of law, but it is only a mile away from Little Rock Central High School, where, with the help of federal troops, the law won a great victory.

(

Cindy Momchilov

)

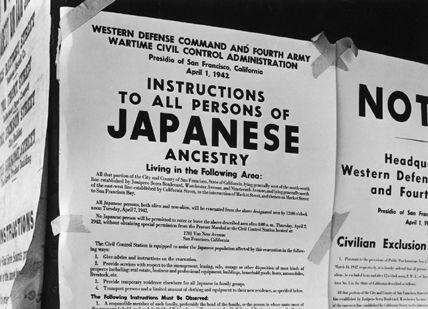

A notice ordering persons of Japanese ancestry to report for internment during World War II.

(

Dorothy Lange/Time and Life Pictures/Getty Images

)

This is one of the places to which those of Japanese ancestry had to report.

(

Corbis

)

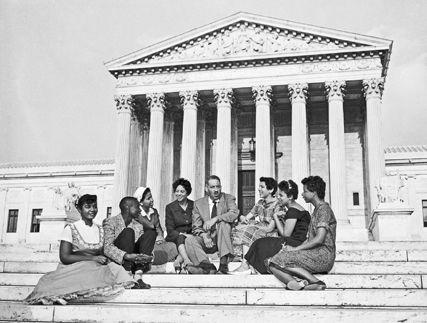

Before he was appointed a justice of the Supreme Court, Thurgood Marshall argued as a lawyer for the plaintiffs (and won) the case of

Brown

v.

Board of Education

. Shown here, he sits on the Court’s front steps with members of the Little Rock Nine.

(

Bettmann/Corbis

)

Background: The Court

T

HOSE NOT FAMILIAR WITH THE

C

OURT MAY BE INTERESTED

in certain essential background facts about how it functions and about the Constitution itself. The Court’s membership changes slowly over time. The Court’s nine members, each appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, serve “during good behavior,” often for life. President Jefferson is remembered to have lamented the fact that Supreme Court judges never retire and they rarely die. In the recent past, the men and women who serve as justices have tended to come from professional judicial backgrounds. In the past, former senators, former governors, former cabinet members, and even a former president have served as justices, but more recently the men and women who serve on the Court have served as judges in lower courts (typically federal courts of appeals), and, like most federal judges, they have begun their judicial careers in midlife after previous legal experience, practicing or teaching law.

1

The Court’s decision-making role is more limited than many imagine. Its work focuses solely upon the interpretation and application of federal law. That law—the federal Constitution, congressional statutes, federal agency action—is itself limited, because the fifty states (each of which has a legislature, governor, and judicial system), not the federal government, are responsible for much of American law, including family law, property law, most tort law, business law, and criminal law. Perhaps 95 percent or more of all judicial proceedings take place in state courts.

Within the area of federal law itself, the Court hears only a handful of cases, mostly those that require the Court to resolve conflicts of interpretation among different lower courts. To put the caseload in perspective, consider that litigants file around forty-five million cases in all state and federal courts each year. Of these, I would guess that about eighty thousand to a hundred thousand may both raise a question of federal laws and reach the stage where a federal court of appeals or final state court decides that question. In about eight thousand of these cases, the losing litigant will ask the Supreme Court to hear the case. The Court in a year will fully hear and decide about eighty of those cases. Thus, those cases that the Court fully hears amount to a virtually invisible tip of a giant iceberg.

2

These eighty cases, while few in number, are important in kind. Because the Court typically hears cases in which different lower courts have decided the same legal question in opposite ways, the Court’s decision, resolving the conflict, will almost always have considerable legal significance. And, as the Court’s history shows, decisions in some cases—for example, those involving desegregation or electoral reapportionment—have changed the life of our nation. In short, the Court comprises a small number of men and women of diverse views and backgrounds, appointed for life, who decide a small number of cases involving federal law. The Court’s decisions are usually final and frequently have considerable legal and practical impact.

In reading this book, one needs to understand a few basic features of the Constitution. (I exhort readers who have not done so—and those who have not done so recently—to read the Constitution itself; it is an admirably concise document.) The document, adopted in 1789, almost immediately amended with a Bill of Rights, and subsequently amended a further seventeen times, establishes a federal government. From the time of its adoption, the Constitution with its Bill of Rights provided a framework for democratic government. The framework included an explicit delegation of powers to the federal government (reserving all others to the states); an allocation of governmental powers (among three branches, legislative, executive, and judicial); protections, particularly in the Bill of Rights, of certain individual liberties, including speech, press, religion, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures, and the payment of compensation for the taking of private

property, as well as guarantees of fair procedures for those threatened with criminal prosecution.