Life in a Medieval Village (7 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Village Online

Authors: Frances Gies

Many manors also had a woodward to see that no one took from the lord’s wood anything except what he was allowed by custom or payment; some also had a cart-reeve with specialized functions. One set of officials no village was ever without was the ale tasters, who assessed the quality and monitored the price of ale brewed for sale to the public. This last was the only village office ever filled by women, who did most of the brewing.

At Elton the titles “beadle” and “hayward” were both in use. Both offices may have existed simultaneously, with the beadle primarily responsible for collecting rents and the fines levied in court. The beadle’s compensation consisted of partial board at the manor house plus exemption from his labor obligation (half the reeve’s, or 58V2 days a year, since he owed for a half rather than a full virgate). At Elton a reap-reeve was sometimes appointed in late summer to help police the harvest work, a function otherwise assigned to two “wardens of the autumn.”

44

The primary aim of estate management was to provide for the lord’s needs, which were always twofold: food for himself and his household, and cash to supply needs that could not be met from the manors. Many lay barons collected their manorial product in person by touring their estates annually manor by manor. Bishop Grosseteste advised careful planning of the tour. It should begin after the post-Michaelmas “view of account,” when it would be possible to calculate how lengthy a visit each manor could support. “Do not in any wise burden by debt or long residence the places where you sojourn,” he cautioned, lest

the manorial economy be so weakened that it could not supply from the sale of its products cash for “your wines, robes, wax, and all your wardrobe.”

45

For Ramsey Abbey and other monasteries, such peripatetic victualing was not practical. Instead, several manors, of which Elton was one, were earmarked for the abbey food supply and assigned a quota, or “farm,” meaning sufficient food and drink to answer the needs of the monks and their guests for a certain period.

46

Whatever the arrangement for exploitation of the manors, the thirteenth-century lord nearly always received his income in both produce and cash. The demesne furnished the great bulk of the produce, plus a growing sum in cash from sales at fair or market. The tenants furnished the bulk of the cash by their rents, plus some payments in kind (not only bread, ale, eggs, and cheese, but in many cases linen, wool cloth, and handicraft products). Cash also flowed in from the manorial court fines. Only a few lords, such as the bishop of Worcester, enjoyed the convenience of a revenue paid exclusively in cash.

47

Cultivation of the demesne was accomplished by a combination of the villein tenants’ contribution of week-work and the daily labor of the demesne staff, the

famuli.

In England the tenants generally contributed about a fourth of the demesne plowing, leaving three fourths to the

famuli.

48

At Elton these consisted of eight plowmen and drivers, a carter, a cowherd, a swineherd, and a shepherd, all paid two to four shillings a year in cash plus “livery,” an allowance of grain, flour, and salt, plus a pair of gloves and money for their Christmas oblation.

49

Smaller emoluments were paid to a cook, a dairyman or dairymaid, extra shepherds, seasonal helpers for the cowherd and swineherd, a keeper of bullocks. a woman who milked ewes. and a few other seasonal or temporary hands.

50

On some manors the

famuli

were settled on holdings, one version of which was the “sown acre,” a piece of demesne land sown with grain. Ramsey Abbey used the sown acre to compensate its own huge

familia

of eighty persons.

51

Another arrangement was the “Saturday plow,” by which the lord’s plow cohort was lent one day a week to plow the holdings of

famuli.

52

The manorial plowman was responsible for the well-being of his plow animals and the maintenance of his plows and harness.

Seneschaucie

stressed the need for intelligence in a plowman, who was also expected to be versed in digging drainage ditches. As for plow animals, Walter of Henley judiciously recommended both horses and oxen, horses for their superior work virtues, oxen for their economy. An old ox was edible and, fattened up, could be sold for as much as he had cost, according to Walter (actually, for 90 percent of his cost, according to a modern scholar; in the 1290s, about 12 shillings). Pope Gregory III had proscribed horsemeat in 732, and though most of Europe ignored the ban, in the Middle Ages and long after, in England horsemeat was never eaten. Consequently an old plow horse fetched less than half his original cost of ten to eleven shillings.

53

Elton’s bailiff or the Ramsey steward may have studied Walter of Henley, because the eight Elton demesne plowmen and drivers used ten stots (work horses) and eighteen oxen in their four plow teams. Horses and oxen were commonly harnessed together, a practice also recommended by Walter. In the Elton region (East Midlands) a popular combination was two horses and six oxen.

54

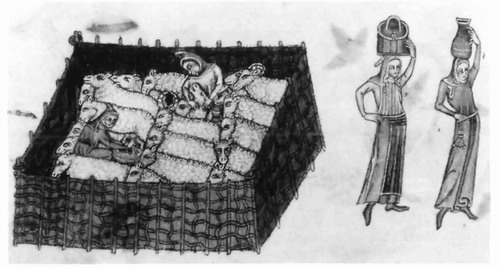

Sheepfold. Man at center is doctoring a sheep, while woman on the left milks and women on the right carry jars of milk. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 163v.

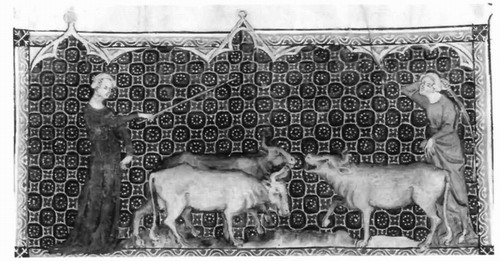

Cattle being driven by herdsmen. British Library, Queen Mary’s Psalter, Ms. Royal 2B Vii, f. 75.

On every manor the tenants’ labor was urgently required in one critical stretch of the annual cycle, the boon-works of autumn and post-autumn. To get the demesne harvest cut, stacked, carted, threshed, and stored and the winter wheat planted before frost called for mass conscription of villeins, free tenants, their families, and often for recruitment of extra labor from the floating population of landless peasants. At Elton, two

meiatores,

professional grain handlers, and a professional winnower were taken on at harvest time.

55

Threshing, done in the barn, was a time-consuming job, winnowing an easy one. Hired labor was paid a penny per ring of threshed wheat, a penny per eight rings winnowed.

56

The staple crops at Elton were those of most English manors: barley, wheat, oats, peas, and beans, and, beginning in the late

thirteenth century, rye. The proportions in the demesne harvest

of 1286 were about two thousand bushels of barley, half as much wheat, and lesser proportions of oats, drage (mixed grain), and peas and beans.

57

Yields were four to one for barley, four to one for wheat, a bit over two to one for oats, and four to one for beans and peas. The overall yield was about three and two-thirds to one, better than the three and one-third stipulated in the

Harrowing. Man following the harrow is planting peas or beans, using a stick as a seed drill. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 171.

Rules of St. Robert.

58

In 1297 the Elton wheat yield reached fivefold, but overall the ratio remained about the same, a third to half modern figures.

59

Prices fluctuated considerably over the half-century from 1270 to 1320, varying from five to eight shillings a quarter (eight bushels) for wheat.

60

Half a ring (two bushels) planted an acre. Even without drought or flood, labor costs and price uncertainty could make a lord’s profit on crops precarious.

The treatises offered extensive advice on animal husbandry—standards for butter and cheese production, advice on milk versus cheese, on suspension of the milking of cows and ewes to encourage early breeding, on feeding work animals (best for the reeve or hayward to look to, since the oxherd might steal the provender), and on branding the lord’s sheep so that they could be distinguished from those of the tenants. The cowherd should sleep with his animals in the barn, and the shepherd should do the same, with his dog next to him.

61

In the realm of veterinary medicine, the best that can be said is that it was no worse than medieval human medicine. Without giving specific instructions, Walter of Henley advocated making an effort to save animals: “If there be any beast which begins to fall ill, lay out money to better it, for it is said in the proverb, ‘Blessed is the penny that saves two.’ ”

62

Probably more practical was Walter’s advice to sell off animals quickly when disease threatened the herd. Verdigris (copper sulfate), mercury, and

tar, all items that appear frequently in the Elton manorial accounts, were applied for a variety of animal afflictions, with little effect on the prevailing rate of mortality, averaging 18 percent among sheep.

63

Sheep pox, “Red Death,” and murrain were usually blamed, the word “murrain” covering so many diseases that it occurs more often in medieval stock accounts than any other.

64

The Elton dairy produced some two hundred cheeses a year, most if not all from ewes’ milk, with the bulk of the product going to the cellarer of the abbey, some to the

famuli

and boon-workers.

65

Most of the butter was sold, some of the milk used to nurse lambs. The medieval practice of treating ewes as dairy animals may have hindered development of size and stamina. But though notoriously susceptible to disease, sheep were never a total loss since their woolly skins (fells) brought a good price. The relative importance of their fleece caused medieval flocks to have a composition which would seem odd to modern sheep farmers. Where modern sheep are raised mainly for meat and the wethers (males) are slaughtered early, in the Middle Ages the wethers’ superior fleece kept them alive for four to five years.

66

Poultry at Elton, as on most manors, was the province of a dairymaid, who, according to

Seneschaucie,

ought to be “faithful and of good repute, and keep herself clean, and…know her business.” She should be adept at making and salting cheese, should help with the winnowing, take good care of the geese and hens, and keep and cover the fire in the manor house.

67

The only other agricultural products at Elton were flax, apples, and wax, all cultivated on a modest or insignificant scale.

68

The wax was a scanty return on a beekeeping enterprise that failed through a bee disease. On other English manors a variety

of garden vegetables, cider, timber, and brushwood were market

products. Wine, a major product on the Continent, was a minor one in England.

In the old days of subsistence agriculture, when the manor’s produce went to feed the manor and the clink of a coin was

Beehive. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 204.