Life in a Medieval Village (6 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Village Online

Authors: Frances Gies

The steward appeared in each village only at intervals, usually no more than two or three times a year, for a stay of seldom

more than two days. The lord’s deputy on each manor throughout the year was the bailiff. Typically appointed on the steward’s recommendation, the bailiff was socially a step nearer the villagers themselves, perhaps a younger son of the gentry or a member of a better-off peasant family. He could read and write; seigneurial as well as royal officialdom reflected the spread of lay literacy.

23

The bailiff combined the personae of chief law officer and business manager of the manor. He represented the lord both to the villagers and to strangers, thus acting as a protector of the village against men of another lord. His overriding concern, however, was management of the demesne, seeing that crops and stock were properly looked after and as little as possible stolen. He made sure the manor was supplied with what it needed from outside, at Elton a formidable list of purchases: millstones, iron, building timber and stone, firewood, nails, horseshoes, carts, cartwheels, axles, iron tires, salt, candles, parchment, cloth, utensils for dairy and kitchen, slate, thatch, quicklime, verdigris, quicksilver, tar, baskets, livestock, food. These were bought principally at nearby market towns, Oundle, Peterborough, St. Neots, and at the Stamford and St. Ives fairs. The thirteenth-century manor was anything but self-sufficient.

Walter of Henley, himself a former bailiff, advised lords and stewards against choosing from their circle of kindred and friends, and to make the selection strictly on merit.

24

The bailiff was paid an excellent cash salary plus perquisites, at Elton twenty shillings a year plus room and board, a fur coat, fodder for his horse, and twopence to make his Christmas oblation (offering). Two other officials, subordinate to the bailiff, are mentioned in the Elton accounts: the

claviger

or macebearer, and the serjeant, but both offices seem to have disappeared shortly after 1300.

25

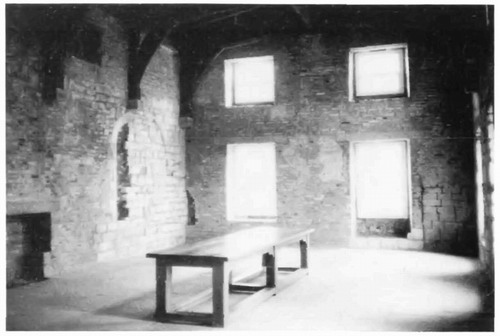

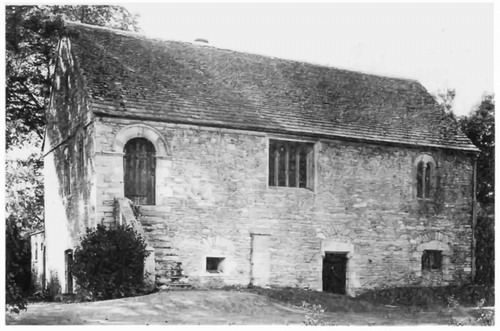

The bailiff’s residence was the lord’s manor house. Set clearly apart from the village’s collection of flimsy wattle-and-daub dwellings, the solid-stone, buttressed manor house contrasted with them in its ample interior space and at least comparative comfort. The main room, the hall, was the setting for the manorial court, but otherwise remained at the bailiff’s disposal.

There he and his family took their meals along with such members of the manorial household as were entitled to board at the lord’s table, either continuously or at certain times, plus occasional visitors. A stone bench at the southern end flanked a large rectangular limestone hearth. The room was furnished with a trestle table, wooden benches, and a “lavatorium,” a metal washstand. A garderobe, or privy, adjoined. One end of the hall was partitioned off as a buttery and a larder. The sleeping chamber whose existence is attested by repairs to it and to its door may have been a room with a fireplace uncovered by the excavations of 1977. A chapel stood next to the manor house.

26

For the entertainment of guests “carrying the lord’s writ,” such as the steward or the clerk of the accounts, the bailiff kept track of his costs and submitted the expenses to Ramsey. Visitors included monks and officials on their way to the Stamford Fair, or to be ordained in Stamford; other ecclesiastics, among them the abbot’s two brothers and the prior of St. Ives; and royal officials—the justice of the forest, the sheriff of Huntingdon,

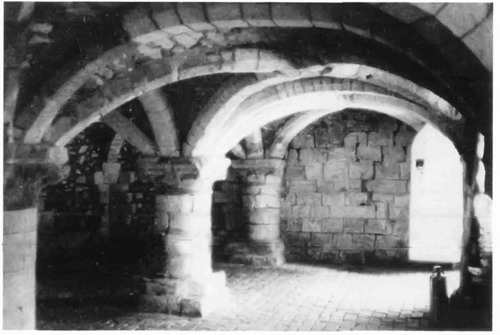

Manor house, c. 1170, at Burton Agnes (Humberside): ground-floor undercroft.

Manor house, Burton Agnes: upper hall.

kings’ messengers, and once “the twelve regarders,” knights who enforced the king’s forest law.

27

The guests’ horses and dogs had to be lodged and fed, and sometimes their falcons, including “the falcons of the lord abbot.”

28

In 1298 when the royal army was on its way to Scotland, a special expense was incurred, a bribe of sixpence to “a certain man of the Exchequer of the lord king…for sparing our horses.”

29

On several later occasions expenses are noted either for feeding military parties or bribing them to go elsewhere.

Assisting the bailiff was a staff of subordinate officials chosen annually from and usually (as in Elton) by the villagers themselves. Chief of these was the reeve. Always a villein, he was one of the most prosperous—“the best husbandman,” according to

Seneschaucie.

30

Normally the new reeve succeeded at Michaelmas (September 29), the beginning of the agricultural year. His main duty was seeing that the villagers who owed labor service rose promptly and reported for work. He supervised the formation

Manor house at Boothby Pagnell (Lincolnshire), c. 1200, also built with an undercroft and an upper hall. Royal Commission on the Historic Monuments of England.

of the plow teams, saw to the penning and folding of the lord’s livestock, ordered the mending of the lord’s fences, and made sure sufficient forage was saved for the winter.

31

Seneschaucie

admonished him to make sure no herdsman slipped off to fair, market, wrestling match, or tavern without obtaining leave and finding a substitute.

32

He might, as occasionally at Elton, be entrusted with the sale of demesne produce. On some manors the reeve collected the rents.

But of all his numerous functions, the most remarkable was his rendition of the demesne account. He produced this at the end of the agricultural year for the lord’s steward or clerk of the

accounts. Surviving reeves’ accounts of Elton are divided into

four parts: “arrears,” or receipts; expenses and liveries (meaning deliveries); issue of the grange (grain and other stores on hand in the barns); and stock. The account of Alexander atte Cross, reeve in 1297, also appends an “account of works” performed by the tenants.

Each part is painstakingly detailed. Under “arrears” are given the rents collected on each of several feast days when they fell

due, the rents that remained unpaid for whatever reason, and receipts from sales of grain, stock, poultry, and other products. Under “expenses and liveries” are listed all the bacon, beef, meal, and cheeses consigned to Ramsey Abbey throughout the year, and the mallards, larks, and kids sent to the abbot at Christmas and Easter. Numerous payments to individuals—carpenter, smith, itinerant workmen—are listed, and purchases set down: plows and parts, yokes and harness, hinges, wheels, grease, meat, herring, and many other items. The “issue of the grange” in 1297 lists 486 rings and 1 bushel of wheat totaled from the mows in the barn and elsewhere, and describes its disposal: to Ramsey, in sales, in payment of a debt to the rector, and for boon-works; then it does the same for rye, barley, and the other grains. In the stock account, the reeve lists all the animals—horses, cattle, sheep, pigs—inherited from the previous year, notes the advances in age category (lambs to ewes or wethers, young calves to yearlings), and those sold or dead (with hides accounted for).

33

With no formal schooling to draw on, the unlettered reeve kept track of all these facts and figures by means of marks on a tally stick, which he read off to the clerk of the accounts. Written out on parchment about eight inches wide and in segments varying in length, sewed together end to end, the account makes two things clear: the medieval manor was a wellsupervised business operation, and the reeve who played so central a role in it was not the dull-witted clod traditionally evoked by the words “peasant” and “villein.”

The accounts often resulted in a small balance one way or the other. Henry Reeve, who served at Elton in 1286-1287, reported revenues of 36 pounds,

1

/

4

penny, and expenditures of 36 pounds 15

3

/

4

pence, which he balanced with the conclusion: “Proved, and so the lord owes the reeve 15

1

/

2

pence.”

34

His successor, Philip of Elton, who took over in April 1287, reported on the following Michaelmas receipts of 26 pounds 6 shillings 7 pence, expenditures of 25 pounds 16 shillings

1

/

4

penny: “Proved and thus the reeve owes the lord 10 shillings 6

3

/

4

pence.”

35

For his labors, physical and mental, the reeve received no cash

stipend, but nevertheless quite substantial compensation. He was always exempted from his normal villein obligations (at Elton amounting to 117 days’ week-work), and at Elton, though not everywhere, received at least some of his meals at the manor house table. He also received a penny for his Christmas oblation.

36

On some less favored manors, candidates for reeve declined the honor and even paid to avoid it, but most accepted readily enough. At Broughton the reeve was given the privilege of grazing eight animals in the lord’s pasture.

37

That may have been the formal concession of a privilege already preempted. “It would be surprising,” says Nigel Saul, “if the reeve had not folded his sheep on the lord’s pastures or used the demesne stock to plow his own lands.”

38

There were many other possibilities. Chaucer’s reeve is a skillful thief of his lord’s produce:

Well could he keep a garner and a bin,

There was no auditor could on him win.

39

Walter of Henley considered it wise to check the reeve’s bushel measure after he had rendered his account.

40

Some business-minded lords assigned quotas to their manors—annual quantities of wheat, barley, and other produce, fixed numbers of calves, lambs, other stock, and eggs. The monkish board of auditors of St. Swithun’s Abbey enforced their quotas by exactions from the reeve, forcing him to make up out of his pocket any shortfall. It might be supposed that St. Swithun’s would experience difficulty in finding reeves. Not so, however. The monks were strict, but their quotas were moderate and attractively consistent, remaining exactly the same year after year for long stretches—60 piglets, 28 goslings, 60 chicks, and 300 eggs—making it entirely possible, or rather probable, that the reeve profited in most years, adding the surplus goslings and piglets to his own stock.

41

The reeve in turn had an assistant, known variously as the beadle, hayward, or messor, who served partly as the reeve’s deputy, partly in an independent role. As the reeve was traditionally a villein virgater, his deputy was traditionally a villein half-virgater, one of the middle-level villagers.

The beadle or hayward usually had primary responsibility for the seed saved from last year’s crop, its preservation and sowing, including the performances of the plowmen in their plowing and harrowing, and later, in cooperation with the reeve, for those of the villeins doing mowing and reaping. Walter of Henley warned that villeins owing week-work were prone to shirk: “If they do not [work] well, let them be reproved.”

42

The hayward’s job also included impounding cattle or sheep that strayed into the demesne crop and seeing that their owners were fined.

43