Just in Case (54 page)

3.

Preheat.

Plug in the dehydrator to preheat.

4.

Prep and pretreat.

Slice, dice, or otherwise prepare your food as necessary. Small fruits or vegetables, such as peas, can be dried whole. Larger fruits or vegetables should be cut into uniform smaller pieces. As is the case for freezing, some foods benefit from a pretreatment before being dried. If a recipe or drying instruction calls for

blanching,

that means you must heat the food in boiling water for a few minutes and then cool it rapidly, usually by plunging it into cold water. Blanching slows the enzyme action that causes food to spoil, sets the color, and speeds the drying time by softening cell walls and allowing water to escape more easily. The other widely used pretreatment is

dipping,

which calls for dipping food in salt water, ascorbic acid, or lemon or other acidic juice. Dipping is used especially for cut fruits, which may otherwise discolor and be unappealing.

5.

Dry.

Place the food on the dehydrator trays and dry according to the manufacturer’s directions. The amount of time it takes to dry a food is determined by many factors, including the food’s size and original moisture content, ambient humidity, and the drying temperature, so it is difficult to give hard and fast rules about drying times. Most drying charts give ranges rather than exact drying times. Serious dehydrators weigh produce to determine when enough moisture has been released, but I don’t have the equipment or the inclination. I dry string beans until they are tough and leathery, peas until they are hard, and onions and peppers until brittle.

6.

Store.

Package dried food in small batches in airtight bottles or plastic bags. Store in a cool, dry, dark place. (Note: Dried foods are not heated at a high enough temperature to kill all insect eggs. If I plan to store dried foods for more than two to three months, I freeze them before storing to kill any insect larvae.)

7.

Use up.

Home dehydrators will not remove enough moisture to match the indefinite storage life of commercially dried foods. Mine start to look a bit old after three to four months.

DRIED APPLE RINGS

As I said, apples are my family’s favorite dried food, and they’re popular with most people, including kids. Apples are fun to dehydrate, but it takes time to cut them up unless you have an apple peeler/corer. I don’t peel my apples, which saves a lot of time. And I dry them as follows:

• Cut your apples into !4 -inch rings and remove the cores.

• Pretreating is only necessary if you are drying in the sun. If so, soak the apples in diluted lemon juice, about !4 cup lemon juice to 4 cups water, for about an hour.

• Wipe off as much of the surface moisture as you can, then dry the slices in your dehydrator for 6 to 8 hours, or until the slices are leathery and chewy.

• Store in an airtight container, where the apples will last a long time — if you can keep the kids out of them. I can’t, so length of storage is not something I worry about.

FRUIT LEATHER

Supermarket fruit leather is primarily sugar and artificial thickener along with a hefty dose of artificial color. Real fruit leather is easy to make and tastes terrific.

• Prepare a thick fruit puree in a blender.

• Spread the puree either on oiled trays to dry in the oven at 120°F or on special fruit-leather inserts for a dehydrator. The length of drying time will depend on the thickness of the puree and other variables; it takes about six hours for a thin sheet to dry in my dehydrator. Turn the sheet over in the last hour so that it dries evenly.

• Once the leather sheet is dry, dust it with cornstarch and roll it into tubes.

• For longterm storage, keep fruit leather in a very cool, dark, dry location. However, this is one of the foods that never sticks around long enough at my house for length of storage to be a problem.

JERKY

I have never dried meat, although I have friends who make their own jerky that is very good. I include the recipe in case you want to try it. You might want to try it with someone who has some experience for the first few times. If you find yourself with an abundance of meat to preserve and no freezer, knowing how to make jerky will come in handy.

• Start with fresh, very lean meat. Trim any excess fat. You can’t make jerky from raw pork or any fowl, but beef and game such as venison or bear is good for jerking.

• Cut the meat into very thin strips. This may be easier to do if the meat is very cold or even partially frozen.

• Boil the meat briefly, just long enough to get the pink out.

DRIED FRUITS VERSUS VEGETABLES

While dried fruit, which most kids like and are familiar with, is one thing, dried vegetables are another. They have two problems: they look funny (read: unappetizing), and they don’t measure up to fresh in the same way canned or frozen vegetables do once cooked. But do not dismiss them too quickly. As long as you don’t expect a dried pea to look or behave like its fresh counterpart, you will find the dried variety has its uses, especially in a food storage system. For instance, if my home-canned spaghetti sauce is a little thinner than I like, I will toss in a half to one cup of dried summer squash. This thickens up the sauce without changing the flavor. In long-cooking soups and stew, dried vegetables such as peppers, onions, peas, and string beans hydrate as they are cooking and taste as good as fresh.

• Combine the jerky blend (see recipe below) with just enough water to cover the meat. Marinate the meat in the mixture overnight.

• Pat the meat dry and put it in your dehy-drator. Do not let pieces touch. The meat will drain a bit, and you will want to keep this cleaned up. The meat may also sweat. Blot off these beads of oil with a paper towel.

• When the meat is dry but still pliable, it is done. Store it in airtight jars or plastic bags or freeze it for longterm storage.

JERKY BLEND

1

teaspoon ground black pepper

8

tablespoons tamari

16

cloves of garlic, crushed

4

teaspoons balsamic vinegar

1

teaspoon parsley

DRYING HERBS

Herbs are probably the easiest thing to dry. They can simply be hung in a dry, airy location or put in a dehydrator for a few hours. If you use a dehydrator, be careful not to let them burn. I dry mint, dill, basil, sage, and thyme with excellent results.

When you use dried herbs in your recipes, remember that they are more concentrated than fresh herbs. In general, when a recipe calls for fresh herbs, you can use dried in one-third to one-half the amount called for.

RECONSTITUTING DRIED FOODS

Not all foods need to be reconstituted, or rehydrated, before use. Jerky can be eaten as is, as can most fruits. If you’re going to use a dried vegetable in a soup and it will cook in the broth for more than twenty minutes, generally it won’t need to be rehydrated, as the long soak in the hot soup will do the job for you. If you want to eat a dried vegetable in a different type of dish or as a side dish, though, you must rehydrate it first; even vegetables intended for stews will benefit from being rehydrated first. Cover the vegetable with boiling water and let sit for twenty minutes. As the water is absorbed, you may have to add more to keep the vegetable submerged. Bring water and vegetable to a boil again and cook until tender. The taste and texture can be improved with the addition of a sauce. Fruits can be rehydrated in the same manner before being added to a recipe or consumed warm.

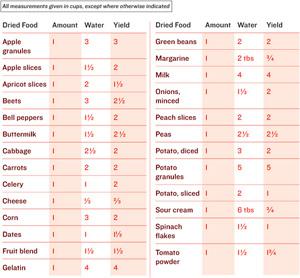

RECDNSTITUTING FDDDS

If a recipe calls for a food you have in dried form, reconstitute first, then proceed as directed.

PICKLING

P

ICKLES ARE JUST

the thing to spice up an otherwise mundane meal, and in the winter months they can provide a taste of summer when you really need a lift. Pickling is not just for cucumbers. It is a great way to keep many fruits and vegetables, especially for your storage pantry, as the process not only preserves but actually enhances many nutrients. My family is particularly fond of pickled beets, carrots, pears, and sauerkraut. Pickling has been documented as early as 1000 BC, but clearly modern techniques and improvements in equipment have made the process much easier.

In general, vegetables are pickled by salting them, letting them sit, then packing them into jars with pickling spices. The jar is filled with either boiling syrup (for sweet pickles) or brine (for salty pickles), and the jars are processed in a water-bath canner (see page 182). You can also find recipes for refrigerator or freezer pickles and some brined pickles that don’t require water-bath canning.

There are several excellent guides to making pickles and relishes, including

The Joy of Pickling,

by Linda Ziedrich, which is my tried-and-true reference. I give here some of my favorite recipes, which will allow you to get a sense of the basic process and, hopefully, a taste for the joys of pickling.

PICKLING SPICES

It will be helpful to make up batches of mixed pickling spices ahead of time so you can make pickles when the mood (or the cucumbers) comes on you.

SWEET AND SPICY MIX

1 or 2

cinnamon sticks, broken into pieces

5

bay leaves, broken up

½ teaspoon dried red chiles, chopped

1

tablespoon black peppercorns

1

tablespoon dill seeds

2

teaspoons fennel seeds

2

teaspoons whole allspice berries

2

teaspoons whole coriander seed

1

teaspoon yellow mustard seeds

1

teaspoon whole cloves

½ teaspoon small pieces nutmeg

• Mix up all the spices and store in a canning jar in a cool, dark place.

MILD PICKLING MIX

This is another good mix that is a bit milder than the mix above.

6

bay leaves, crumbled

2

tablespoons mustard seed

J

teaspoon whole cloves

2

teaspoons allspice berries

2

teaspoons black peppercorns

2

teaspoons dill seed

2

teaspoons coriander seed

• Mix up all the spices and store in a canning jar in a cool, dark place.

PICKLES

To make pickles, you’ll need both white vinegar and pickling salt. Table salt will not do, as it often contains iodine and always has other additives that can ruin the look, if not the flavor, of your pickles. Kosher salt will work, but its crystals are large and you will need about one and a half times as much as you would of pickling or canning salt. If you are just learning how to make pickles, stick to true pickling salt for more reliable results.

BEN’S FAVDRITE SUNSHINE PICKLES

Like so many favorite recipes, I have no idea where it came from. My mother-in-law made these a lot, and they are my youngest son’s favorite.

6 dozen small pickling cucumbers

2 or 3 fresh heads of dill

1 onion, chopped

4 cloves garlic

Dried chiles (optional)

1 quart vinegar

1 quart water

⅔ cup pickling salt

1 tablespoon sugar

• Loosely pack the cucumbers in a 2-gallon jar. Add the dill, onion, garlic, and if you like a pickle with some heat, chiles. Combine the vinegar, water, salt, and sugar in a saucepan, bring to a boil, and pour over the cucumbers. Seal the jar with a lid, then set it in the sun for three days. After that, you can repack the pickles in quart or pint jars and process them in a water-bath canner for 20 minutes (see page 182), or you can just refrigerate them. (They don’t last long enough around here to bother canning.)

EASY PICKLED BEETS

Even kids who hate beets like these.

20-30

medium-size beets

1

quart cider vinegar

1

cup water

⅔ cup sugar

2

tablespoons pickling salt