Interzone 244 Jan - Feb 2013 (21 page)

Read Interzone 244 Jan - Feb 2013 Online

Authors: TTA Press

Tags: #short fiction, #fantasy, #short stories, #science fiction, #sf, #artwork, #reviews, #short fantasy, #interviews, #eric brown, #lavie tidhar, #new authors, #saladin ahmed, #movie reviews, #dvd reviews, #margaret atwood, #tony lee, #jim burns, #jim hawkins, #david langford, #nick lowe, #jim steel, #tracie welser, #ann vandermeer, #george zebrowski, #guy haley, #helen jackson, #karin tidbeck, #ramez naam

This collection is not afraid to push

through the nominal boundaries and venture into a kind of

no-man’s-land where the connection to the genre is tenuous. It

starts off with the very epitome of steampunk, Carrie Vaughan’s

‘Harry and Marlowe and the Talisman of the Cult of Egil’, and then

veers off into uncharted areas such as Jeff VanderMeer’s ‘Fixing

Hanover’, or Ben Peek’s ‘Possession’, where the steampunk itself

provides only the most distant of backdrops.

‘

A Handful of Rice’ by

Vandana Singh could be said to go even further – it eschews the

familiar setting of Victorian England and transplants it to the

Indian Subcontinent. The central pivot of the story is the friction

between the old and the new, between pranic energy and steam-power,

yet the latter is only incidental to the story itself but

nevertheless essential to the telling. Bruce Sterling contributes

‘White Fungus’, set in 2040s Europe amidst a global collapse. Its

crumbling cyberpunk aesthetic (which is, if you think about it, the

logical conclusion of steampunk) signals a harsh critique of

systems reliant on technology, whether those systems are home

computers or large political bodies. It seems to be saying

“

what about people?” Curiously, the story inverts the focus

of hope, from shiny technology to post-steampunk human invention

and resourcefulness.

It is impossible to encapsulate the full

spectrum of instantiations of the genre as contained in this

anthology. It is by turns astonishing and audacious, emphasising

just how wide the spectrum of steampunk can be. Absolutely

essential reading for students of the genre

* *

TAKEN

Benedict Jacka

Orbit pb, 319pp, £7.99

Juliet E. McKenna

Having enjoyed Jacka’s first two books, I

opened

Taken

with mingled anticipation and apprehension.

Book three is often when prior knowledge of character and scenario

becomes essential. That, or painstaking recapping sees the opening

flow like cold treacle. Encouragingly, neither applies.

Alex Verus, low-level divination mage, sits

in a Starbucks waiting to meet an unknown but very powerful mage

woman. As Crystal offers him a job, and he turns it down, Jacka

swiftly and deftly portrays the essentials of Alex’s character and

grounds his story in contemporary London while simultaneously

revealing the perilous parallel world of rival mages of Light and

Dark. A new reader should have no problem picking up the series

here while fans of

Fated

and

Cursed

learn new facets

of Alex’s life. So far, so good.

Alex turns down Crystal’s offer because he

has other responsibilities, notably training his apprentice Luna.

Their relationship is now firmly master and pupil and it’s good to

see Jacka avoiding the urban-fantasy-soap-opera pitfall. Luna’s

currently taking classes in magical duelling. So far, so Harry

Potter? Third books often see a new writer’s imagination running

out of steam and resorting to imitation. Not so here. Jacka draws

on broader traditions of magicians’ apprentices to expand his

magical world. That said, I don’t think Potteresque echoes are

accidental, but an indication that readers and characters alike

shouldn’t leap to assumptions as this story unfolds.

Next, Talisid wants Alex’s help and turning

down a request from a high level Council member isn’t easy. Not

that Alex wants to. Apprentices are disappearing. If Dark mages are

recruiting by abduction, this is serious. Even more so if some

Light mage is letting information slip as to where vulnerable

apprentices might be found, by accident or design. As in the

earlier books, ‘Light’ and ‘Good’ are by no means synonymous. Light

prejudice against magical creatures, the less magically powerful

and particularly the non-magical world becomes apparent and

ultimately significant. Meantime, Dark mages mercilessly pursue

ambitions and grudges alike.

Events take a deadly turn as Alex follows a

promising lead into an unexpected hail of gunfire. Getting out of

that isn’t easy, even if Alex can read the future. Jacka’s

continued inventiveness with spellcraft is a continuing strength of

these books. Magic’s full potential relies on its intelligent use

as well as an understanding of its limits. Though that’s just the

beginning of Alex’s challenges. Some mages would prefer to do away

with all such limitations. A low-level diviner and a few

apprentices can’t battle them.

This finely crafted story is a solidly

satisfying read.

Taken

sees Jacka established as a writer

with a distinctive voice within the best traditions of contemporary

urban fantasy.

* *

ORIGIN

J.T. Brannan

Headline pb, 400pp, £7.99

Ian Hunter

For the world’s self-proclaimed most

reluctant reader,

Origin

appears on the surface to be the

perfect book. Split into five parts and seventy-two chapters, this

has all the hallmarks of a short chapter page-turner. But is it?

Well, we are in Dan Brown-ish territory, I suppose, and before the

supermarket shelves became dominated by paperbacks with black or

grey covers and a photograph of maybe a mask or a glove or a chain,

then

Origin

would have been right up there on the shelves

beside books with three words in the title, with one of them being

Nosferatu, or Lucifer, or Doomsday, or Templar. You get the

picture.

First-time author (and former army officer)

Brennan knows how to spin a yarn at breakneck speed, and the

military antics have more than a ring of authenticity to them. The

action opens down in the Antarctic on Pine Island Glacier, where a

member of an expedition lets his curiosity get the better of him

and falls to what might be his death. His team follows to the

rescue and find what he has just discovered, which is a mummified

body with “anomalous artefacts” as they say in the trade. Something

that couldn’t possibly be, but is, and no sooner does the

expedition reveal that they have discovered something “anomalous”

than shadowy powers, listening in via satellite, quickly join up

the dots and wipe out our band of intrepid explorers. Apart from

team leader Lynn Edwards who has nowhere to turn except into the

waiting arms of ex-husband Matt Adams who, handily, was once a

member of a crack government unit. Their relationship brings to

mind Andy McDermott’s series of books featuring Nina Child and

Eddie Chase.

What follows is the mother of all conspiracy

theories as well as some minor ones, such as the mysterious,

possibly all-powerful Bilderberg Group; theories about the missing

link between man and ape; the remote Area 51 in the Nevada desert;

the Nazca Lines in Peru; and a certain Hadron Collider in Geneva.

To be sure,

Origin

isn’t subtle; there is a tad too much

conspiracy theory dumping, a kitchen sink approach to piling this

“otherness” into the mix, and some fast switching between multiple

viewpoints of different characters, regardless of their importance

to the plot.

My advice? Don’t look down, keep your eyes

straight ahead, and your knuckles white by holding tightly to the

covers of the book until the end.

Origin

isn’t great, but it

isn’t bad either. There is maybe too much going on and the reader’s

incredulity will be stretched with regard to the characterisation,

some of the action, and parts of the plot, but it does what it says

on the tin by providing a few hours of over-the-top entertainment

perfect for the beach, the pool, or before the lights go out, and

it ends in a cliffhanger that just cries out for a sequel.

* *

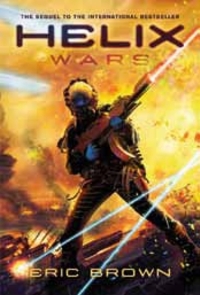

HELIX WARS

Eric Brown

Solaris pb, 383pp, £7.99

Lawrence Osborn

Helix Wars

is the sequel to the 2007

novel

Helix

, which described the arrival of humans on the

Helix, a vast artificial environment created by a race of

benevolent aliens known as the Builders as a refuge for intelligent

races that have been threatened by extinction on their home worlds.

The new story is set some 200 years later. Humans are now

well-established on the Helix and have been appointed by the

Builders to the largely diplomatic role of peacekeeping.

The central character, Jeff Ellis, is a

shuttle pilot who regularly transports peacekeepers to other worlds

of the Helix. However, on this occasion, his shuttle crashes on

Phandra (a world occupied by tiny empathetic humanoids), killing

his passengers and leaving Jeff himself seriously injured.

He is rescued by some Phandrans and restored

to health by Calla, a Phandran healer. It transpires that he was

shot down by the Sporelli, an aggressive authoritarian race who

have invaded Phandra in order to gain access to the natural

resources on another world further along the Helix. As soon as he

is well enough, Jeff sets out with Calla to get news of this

invasion back to the peacekeepers on New Earth. However, the

Sporelli pursue and capture them.

Fortunately for Jeff his crash has come to

the attention of Kranda, a member of the warlike Mahkani (the

Helix’s engineers), whose life he once saved. Because of their code

of honour, she is now bound to rescue him and duly does so with the

aid of some highly advanced Builder technology. Jeff then insists

on rescuing Calla and in the process they save the Helix from an

alien invasion.

Interwoven into this is a secondary story

about Jeff’s marital difficulties. Since the death of their son he

and his wife Maria have grown apart, and Jeff, based on advice from

Calla, clumsily seeks reconciliation. After some spectacular twists

the two storylines merge, Jeff is made an offer he can’t refuse by

the Builders, and they all live happily ever after.

The novel is driven by the well-paced action

of the main storyline, while the secondary storyline adds depth to

Jeff. However, most of the minor characters, particularly the

aliens, are little more than two-dimensional stereotypes.

By contrast, Brown’s description of alien

technologies is very imaginative. The wind-powered mass transport

system on Phandra is refreshingly novel, while the technology

underlying the Helix itself is mind-blowing. Unfortunately he

allows the technology to become a

deus ex machina

by

providing Jeff and Kranda with nearly invulnerable Builder-designed

exo-skeletons that all too easily enable them to overcome the

challenges that face them.

In spite of my reservations, I enjoyed

Helix Wars

. It may not be Eric Brown at his best, but it is

still imaginative, well-paced and easy to read

* *

IN OTHER WORLDS

Margaret Atwood

Virago pb, 272pp, £9.99

Barbara Melville

Margaret Atwood messes with me. Sometimes,

as with

The Handmaid’s Tale

,

Oryx and Crake

and

The Year of the Flood,

this is a positive experience, taking

me on unexpected journeys, and making me think in different ways.

For me, this knack of uprooting people’s thinking is pivotal to

good science fiction. But despite penning these tales, all

frequently considered science fiction, Atwood insists she’s been

miscategorised. Over the years, she’s been challenged and even

chastised for saying so. This collection offers a riposte of sorts,

whilst exploring and celebrating her personal relationship with the

fantastic.

In the book’s earlier essays, Atwood charts

two histories: her own, from childhood to adulthood, and that of

science fiction. The book’s later essays explore and review

specific other worlds, including H. Rider Haggard’s

She

,

Aldous Huxley’s

Brave New World

, and Kazuo Ishiguro’s

Never Let Me Go

. While each essay is taut and engaging, the

book’s overall structure is difficult. The opening essays are the

most powerful, rich in strong ideas and skilfully bonded through

memoir. The later essays are just as riveting but not as personal,

making them harder to get into.

Despite the clunking mechanics of this

setup, these essays share a common thread: the concept of other

worlds. Such worlds, Atwood tells us, may be physical, conceptual

or temporal: alternate realities, other planets or unwritten

futures, to name a few. They may be utopias, dystopias, or both –

what she terms “ustopias”. What these worlds have in common is

their mapping of unknowns.

Atwood’s personal account includes a world

borne of her childhood mind’s creation – Mischiefland – comprising

superheroes of the flying rabbit persuasion. She considers

Mischiefland and others like it as descendants of the earliest

storytelling, and explores why they manifest in the human psyche.

The superhero’s power of flying, as a means of transcending the

body’s material limits, is one such example. Atwood notes the

winged creatures in myths tend to be tricksters, and their stories

warnings. This lust for ideals – and the question of whether or not

to trust them – is an integral theme in this collection.