India (Frommer's, 4th Edition) (298 page)

Mandawa, Jhunjhunu District, Shekhawati 333 704. Reservations: 0141/237-1194

0141/237-1194

or -4112. Fax 0141/237-2084 or 0141/510-6082.

www.castlemandawa.com

. [email protected]. 60 units. Rs 4,000 standard double; Rs 6,000 deluxe cottage; Rs 10,000 suite. Breakfast Rs 350, lunch Rs 600, dinner Rs 650. Taxes extra. AE, MC, V.

Amenities:

Restaurant; bar; badminton; billiard room; children’s play area; cultural performances; helipad; Internet (Rs 50 30 min., 100/hr.); in-house dairy pool; Ayurvedic massage; safaris—camel, horse, and jeep; table tennis;. In room: A/C, fan, minibar (suites only).

SHOPPING

Outside some havelis, caretakers sell Rajasthani puppets and postcards. You can see artisans and craftspeople at work in their shops in Mandawa, along Sonthaliya Gate and the bazaar.

Lac

bangles in bright natural colors make pretty gifts (from as little as Rs 15 each); if you find the sizes too small, have a pair custom-made while you wait. Another good buy is the camel-leather Rajasthani shoes

(jootis),

once a symbol of royalty. The shop at Mandawa’s Desert Resort sells handicrafts in vivid colors, all produced by rural women of the region.

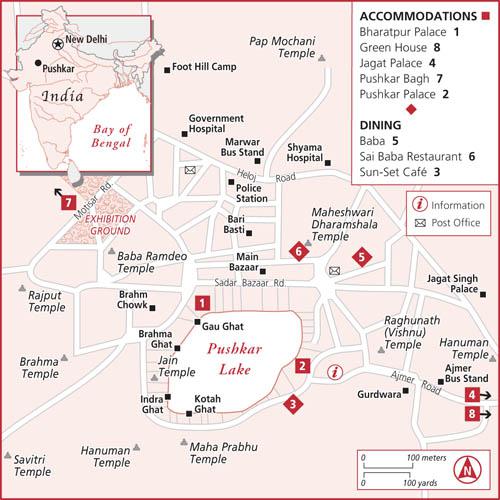

6 Pushkar

288km (179 miles) W of Jaipur

Pushkar

On the eastern edge of the vast Thar Desert, with a beautiful backdrop in the embracing arms of the Aravalli Hills, Pushkar is one of the most sacred—and atmospheric—towns in India. Legend has it that the holy lake at its center was created when Brahma dropped the petals of a lotus flower

(pushpa)

from his hand

(kar).

The tiny temple town that sprung up on the lake shores remains an important pilgrimage site for Hindus, its population swollen dramatically in recent years by the hippies who came for a few days and never left—a sore point for visitors who remember its untouched charm, and a real nuisance for first-time travelers who now discover a town steeped in commercial prospectors who thrive on making a quick buck, often at the expense of Pushkar’s spiritual roots. Their presence has transformed the sleepy desert town into a semi-permanent trance party, however, with

bhang

(marijuana) lassis imbibed at the myriad tiny eateries, falafels on every menu, long-bearded rabbis on bicycles, boys perfectly dressed up like Shiva posing for photographs, and world music pumping from speakers that line the street bazaar that runs along the lake’s northern edge. This street bazaar is the center of all activity in Pushkar and incidentally one of the best shopping experiences in Rajasthan, where you can pick up the most gorgeous throwaway gear, great secondhand books, and mountains of CDs at bargain prices.

Pushkar is something akin to Varanasi, only without the awful road traffic—it really is possible to explore the town entirely on foot, and outside the annual camel

mela.

It doesn’t have the same claustrophobic crowds you find in Varanasi. What you will find exasperating, however, is the tremendous commercialization of just about everything—particularly “spirituality”—except without service standards to match. It takes about 45 minutes to walk around the holy lake and its 52

ghats.

Built to represent each of the Rajput Maharajas who constructed their “holiday homes” on its banks,

ghats

are broad sets of stairs from where Hindu pilgrims take ritual baths to cleanse their souls. Note that you will need a “Pushkar Passport” to perambulate without harassment (see “Passport to Pushkar: Saying Your Prayers,” below), that shoes need to be removed 9m (30 ft.) from the holy lake (bring cheap flip-flops if you’re worried about losing them), and that photography of bathers is prohibited.

Surrounding the lake and encroaching on the hills that enhance the town’s wonderful sense of remoteness are some 500 temples, of which the one dedicated to Brahma, said to be 2,000 years old, is the most famous, not least because it’s one of only a handful in India dedicated to the Hindu Lord of Creation. The doors to the enshrined deity are shut between 1:30 and 3pm, but you can wander around the temple courtyard during these hours. The other two worth noting (but a stiff 50-min. climb to reach) are dedicated to his consorts: It is said that Brahma was cursed by his first wife, Savitri, when he briefly took up with another woman, Gayatri—to this day, the temple of Savitri sits sulking on a hill overlooking the temple town, while across the lake, on another hill, no doubt nervous of retribution, the Gayatri Temple keeps a lookout. Ideally, Savitri should be visited at sunset, while a visit to Gayatri should coincide with the beautiful sunrise.

Note:

The Vishnu temple, encountered as you enter town, is the only temple off-limits to non-Hindus, but photography is permitted from outside the temple gates.

The Dargah Sharif & Other Ajmer Gems

Ajmer is not an attractive town, and most foreigners experience it only as a jumping-off point to the pilgrim town of Pushkar. However, it is worthwhile to plan your journey so that you can spend a few hours exploring Ajmer’s fascinating sights (particularly the Dargah, one of the most spiritually resonant destinations in India) before you head the short 11km (7 miles) over a mountain pass to the laid-back atmosphere of Pushkar and its superior selection of accommodations.

Founded in the 7th century and strategically located within striking distance of the Mewar (Udaipur) and Marwar (Jodhpur) dynasties, as well as encompassing most of the major trade routes, Ajmer has played a pivotal role in the affairs of Rajasthan over the years. The Mughal emperors realized that only by holding this city could they increase their power base in Rajasthan. This is principally why the great Mughal emperor Akbar courted the loyalty of the nearby Amber/Jaipur court, marrying one of its daughters. But Ajmer was important on an emotional and spiritual level too, for only by gaining a foothold in Ajmer could Akbar ensure a safe passage for Muslim pilgrims to

Dargah Sharif

(Khwaja Moin-ud-Din Chisti’s Dargah).

The great Sufi saint Khwaja Moin-ud-Din Chisti, “protector of the poor,” was buried here in 1235.

Said to possess the ability to grant the wishes and desires of all those who visit it, the

Dargah Sharifis the most sacred Islamic shrine in India, and a pilgrimage here is considered second in importance only to a visit to Mecca. After a living member of the Sufi sect, Sheikh Salim Chisti, blessed Akbar with the prophecy of a much-longed-for son (Emperor Jahangir, father of Shah Jahan, builder of the Taj), Emperor Akbar himself made the pilgrimage many times, traveling on foot from distant Fatehpur Sikri and presenting the shrine with cauldrons (near the entrance) large enough to cook food for 5,000 people. It was not only Akbar and his offspring who made the pilgrimage—even the Hindu Rajputs came to pay homage to “the divine soul” that lies within.

Today the shrine still attracts hundreds of pilgrims every day, swelling to thousands during special occasions such as Urs Mela (Oct/Nov), the anniversary of Akbar’s death. Leaving your shoes at the entrance (Rs 10/at exit), you pass through imposing

Nizam Gate

and smaller

Shahjahani Gate;

to the right is

Akbar’s mosque,

and opposite is the equally imposing

Buland Darwaza.

Climb the steps to take a peek into the

two huge cauldrons

(3m/10 ft. round) that flank the gates—they come into their own at Urs when they are filled to the brim with a rice dish that is then distributed to the poor. To the right is

Mehfil Khana,

built in 1888 by the Nizam of Hyderabad. From here you enter another gateway into the courtyard, where you will find another mosque on the right, this one built by Shah Jahan in his characteristic white marble. You’ll also see the great

Chisti’s Tomb

—the small building topped by a marble dome and enclosed by marble lattice screens. In front of the tomb, the qawwali singers are seated, every day repeating the same beautiful haunting melodies (praising the saint) that have been sung for centuries. Everywhere, people abase themselves and sing, their eyes closed, hands spread wide on the floor or clutching their chests, while others feverishly pray and knot bits of fabrics to the latticework of the tomb or shower it with flowers. The scene is moving, the sense of faith palpable and, unlike the Dargah in Delhi, the atmosphere welcoming (though it’s best to be discreet: no insensitive clicking of cameras or loud talking). Entry is free, but donations, paid to the office in the main courtyard, are welcome and are directly distributed to the poor. Entered off Dargah Bazaar, the Dargah is open daily, from 4 or 5am to 9 or 10pm (except during prayer times) depending on the season.

Having laid claim to Ajmer through a diplomatic marriage, Akbar built a red-sandstone fort he called

Daulat Khana

(Abode of Riches)

in 1572. This was later renamed the Magazine by the British, who maintained a large garrison here, having also realized Ajmer’s strategic importance. In 1908 it was again transformed, this time into the largely missable

Rajputana Museum

(small fee; Sat–Thurs 10am–4:30pm). The fort is significant mostly from a historical perspective, for it is here in 1660 that the British got a toehold in India when Sir Thomas Roe, representative of the British East India Company, met Emperor Jahangir and gained his permission to establish the first British factory at Surat.