India After Gandhi (16 page)

Read India After Gandhi Online

Authors: Ramachandra Guha

Tags: #History, #Asia, #General, #General Fiction

In the first week of March 1948, the editor of the

Sunday Times

wrote to Noel-Baker that, ‘in the world struggle for and against Communism, Kashmir occupies a place more critical than most people realise. It is the one corner at which the British Commonwealth physically touches the Soviet Union. It is an unsuspected soft spot, in the perimeter of the Indian Ocean basin, on whose inviolability the whole security of the Commonwealth and indeed world peace depend.’

51

By now, Nehru bitterly regretted going to the United Nations. He was shocked, he told Mountbatten, to find that ‘power politics and not ethics were rulingan organization which ‘was being completely run by the Americans’, who, like the British, ‘had made no bones of [their] sympathy for the Pakistan case’.

52

Within the Cabinet, pressure grew for the renewal of hostilities, for the throwing out of the invaders from northern Kashmir. But was this militarily feasible? A British general with years of service in the subcontinent warned that

Kashmir may remain a ‘Spanish Ulcer . I have not found an Indian familiar with the Peninsular War’s drain on Napoleon’s manpower and treasure: and I sometimes feel that Ministers areloath to contemplate such a development in the case of Kashmir – I feel they still would prefer to think that the affair is susceptible of settlement, in a short decisive campaign, by sledge-hammer blows by vastly superior Indian forces which should be ‘thrown’ into Kashmir.

53

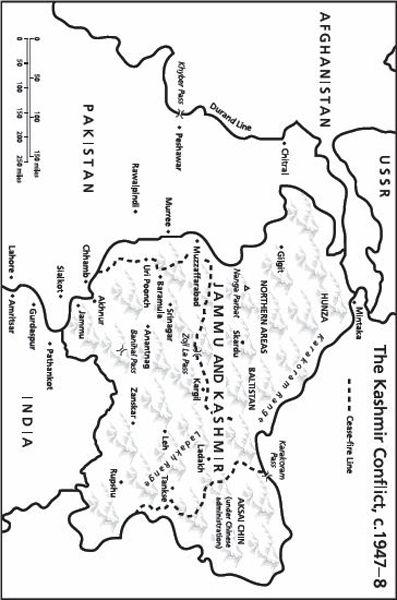

Meanwhile, in March 1948 Sheikh Abdullah replaced Mehr Chand Mahajan as the prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir. Then, in the middle of May, when the snows had melted, the war recommenced. An infantry brigade advanced north and west from Uri. It took the town of Tithwal, butmet with sharp resistance en route to the key town of Muzaffarabad.

54

On the otherside of an ever-shiftingline of control, Pakistan had sponsored a government of Azad (Free) Kashmir. They had also created an Azad Kashmir army, manned by men from these parts of the state, helped and guided by Pakistan army officers. These forces were skilful in their use of the terrain. In the late summerof 1948 they took the towns of Kargil and Dras, and threatened the capital of Ladakh, Leh, which is at an altitude of 11,000 feet. However, an Indian air force squadron was successful in bringing supplies to Leh. It was also the air force that brought relief to the town of Poonch, in the west, whose surroundings were under the control of the raiders.

55

The two armies battled on through the later months of 1948. In November both Dras and Kargil were recaptured by the Indians, making Leh and Ladakh safe for the moment.In the same month the hills around Poonch were also cleared. However, the northern and western parts of Kashmir were still in the control of Pakistan. Some Indian commanders wanted to move on, and asked for the redeployment of three brigades from the plains. Their request was not granted. For one thing, winter was about to set in. For another, the offensive would have required not merely troop reinforcements, but also massive air support.

56

Perhaps it was as well that the Indian Army halted its forward movement. For, as a scholar closely following the Kashmir question commented at the time,‘either it must be settled by partitionor India will have to walk into West Punjab. Amilitary decision can

never

be reached in Kashmir itself.’

57

At the United Nations a Special Commission had been appointed for Kashmir. Its members made an extensive tour of the region, visiting Delhi, Karachi and Kashmir. In Srinagar they were entertained by Sheikh Abdullah at the famous Shalimar Gardens. Later, Abdullah had a long talk with one of the UN representatives, the Czech diplomat and scholar Josef Korbel. The prime minister dismissed both a plebiscite and independence, arguing that the ‘only solution’ was the partition of Kashmir. Otherwise, said Abdullah, ‘the fighting will continue; India and Pakistan will prolong the quarrel indefinitely, and our people’s suffering will go’.

In Srinagar Korbel went to hear Abdullah speak at a mosque. The audience of 4,000 listened ‘with rapt attention, their faith and loyalty quite obvious in their faces. Nor could we notice any police, so often used to induce such loyalty.’ The Commission then visited Pakistan, where they found that it would not consider any solution which gave the vale of Kashmir, with its Muslim majority, to India.

58

By March 1948 Sheikh Abdullah was the most important man in the Valley. Hari Singh was still the state’s ceremonial head – now called ‘sadr-i-riyasat’ – buthe had no real powers. The government of India completely shut him out of the UN deliberations. Their man, as they saw it, was Abdullah. Only he, it was felt, could ‘save’ Kashmir for the Union.

At this stage Abdullah himself was inclined to stress the ties between Kashmir and India. In May 1948 he organized a week-long ‘freedom’ celebration in Srinagar, to which he invited the leading lights of the Indian government. The events on the calendar included folk songs and poetry readings, the remembrance of martyrs and visits to refugee camps. The Kashmiri leader commended the ‘patriotic morale of our own people and the gallant fighting forces of the Indian Union’. ‘Our struggle’, said Abdullah, ‘is not merely the affair of the Kashmir people, it is the war of every sonanddaughter of India.’

59

On the first anniversary of Indian independence Abdullah sent a message to the leading Madras weekly, Swatantra. The message sought to unite north and south, mountain and coast, and, above all, Kashmir and India. It deserves to be printed in full:

Through the pages of SWATANTRA I wish to send my message of fraternity to the people of the south. Farback in the annals of India the south and north met in the land of Kashmir. The great Shankaracharya came to Kashmir to spread his dynamic philosophy but here he was defeated in argument by a Panditani. This gave rise to the peculiar philosophy of Kashmir – Shaivism. A memorial to the great Shankaracharya in Kashmir stands prominent on the top of the Shankaracharya Hill in Srinagar. It is a temple containing the Murti of Shiva.

More recently it was given to a southerner to take the case of Kashmir to the United Nations and, as the whole of India knows, with the doggedness and tenacity that is sousualto the southerner, he defended Kashmir.

We in Kashmir expect that we shall continue to receive support and sympathy from the people of the south and that some day when we describe the extent of our country we shall use the phrase ‘from Kashmir to Cape Comorin’.

60

The Madras journal, for its part, responded by printing alyrical paean to the union of Kashmir with India. ‘The blood of many a brave Tamilian, Andhra, Malayalee and Coorgi’, it said, ‘has soaked into the fertile soil of Kashmir and mixed with the blood ofthe Kashmiri patriots, cementing for ever the unity of the North and the South.’ Sheikh Abdullah’s Id perorations, noted the journal, were attentively heard by many Muslim soldiers from Kerala and Tamil Nadu. In Uri, sixty miles from Srinagar, there was a grave of a Christian soldier from Travancore, which had the Vedic swastika and a verse from the Quran inscribed on it. There could be ‘no more poignant and touching symbolof the essential oneness and unity of India’.

61

Whether or not Abdullah was India’s man, he certainly was not Pakistan’s.In April 1948 he described that country as ‘an unscrupulous and savage enemy’.

62

He dismissed Pakistan as a theocratic state and the Muslim League as ‘pro-prince’ rather than ‘pro-people’. In his view, ‘Indian and not Pakistani leaders . . . had all along stood for the rights of the States’ people’.

63

When a diplomat in Delhi asked Abdullah what he thought of the option of independence, he answered that it would never work as Kashmir was too small and too poor. Besides, said the Sheikh, ‘Pakistan would swallow us up. They have tried it once. They would do it again.

64

Within Kashmir Abdullah gave top priority to the redistribution of

land. Under the maharaja s regime, a few Hindus and fewer Muslims had very large holdings, with the bulk of the rural population serving as labourers or as tenants-at-will. In his first year in power Abdullah transferred 40,000 acres of surplus land to the landless. He also outlawed absentee ownership, increased the tenant s share from 25 per cent to 75 per cent of the crop and placed a moratorium on debt.His socialistic policies alarmed some elements in the government of India, especially as he did not pay compensation to the dispossessed landlords. But Abdullah saw this as crucial to progress in Kashmir. As he told a press conference in Delhi, if he was not allowed to implement agrarian reforms, he would not continue as prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir. Asked what he would doif reactionary elements got the upper hand in the central government, Abdullah answered: ‘Don’t think I will desert you, even if you desert me. I will resign and join those people in the Indian Union who will also fight for economic betterment of the poor.’

65

At this press conference Abdullah also made some sneering remarks about Maharaja HariSingh. He pointed out that the maharaja had run away from Srinagar when it was in danger. In April 1949 Abdullah won a major victory when Hari Singh was replacedas sadr-i-riyasat by his eighteen-year-old son, Karan Singh. The next month Abdullah and three other National Conference men were chosen to represent Kashmir in the Constituent Assembly in Delhi, in a further affirmation of the state’s integration with India.

66

That summer the Valley opened itself once more for tourists. As a sympathetic journalist putit, ‘every tourist who goes to Kashmir this summer will be rendering as vital a service to Kashmir – and to India – as a soldier fighting at the front’.

67

In the autumn came a visitor more important than a million tourists – Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru and Abdullah took aleisurely two-hour ride down Srinagar’s main thoroughfare, the river Jhelum. As their barge rode on, commented the correspondent of

Time

magazine, ‘hundreds of

shikaras

(gondolas) milled around; their jampacked passengers wanted a good look, and they pelted Nehru withflowers’. Thousands watched the procession from the riverbanks, firing crackers from time to time. ‘Carefully coached schoolchildren’ shouted slogans in praise of Nehru and Abdullah. Seizing the chance, merchants had hung out their wares, alongside banners which advertised ‘best Persian and Kashmiri carpets’.

‘All the portents’, concluded Time, were that ‘India considered that

the battle for Kashmir had been won – and that India intended to keep the prize.’

68

V

The battle for Kashmir was, and is, not merely or even mostly a battle for territory. It is, as Josef Korbel put it half a century ago, an ‘uncompromising and perhaps uncompromisable struggle of two ways of life, two concepts of political organization, two scales of values, two spiritual attitudes’.

69

On one side was the idea of India; on the other side, the idea of Pakistan. In the spring of 1948 the British journalist Kingsley Martin visited both countries to see how Kashmir looked from each. Indians, he found, were utterly convinced of the legality of the state s accession, and bitter in their condemnation of Pakistan’s help to the raiders. To them the religion of the Kashmiris was wholly irrelevant. The fact that Abdullah was the popular head of an emergency administration was ‘outstanding proof that India wasnot “Hindustan” and that there are Muslims who have voluntarily chosen to come to an India which, as Nehru emphasised, should be a democracy in which minorities can live safely and freely’.

When Martin crossed the border he found ‘how completely different the situation looks from the Pakistan angle’. Most people he met had friends or relatives who had died at the hands of Hindus and Sikhs. The dispute for the Pakistanis started with the rebellion in Poonch, which in India had been ‘largely and undeservedly forgotten’. In Karachi and Lahore the people were ‘completely sympathetic’ to the raiders from the Frontier who, in their eyes, were fighting ‘a holy war against the oppressors of Islam’.

70

Martin’s conclusions were endorsed by the veteran Australian war correspondent Alan Moorehead. On a visit to Pakistan he too found that the Kashmir conflict was looked upon ‘as a holy Moslem war . . . Some of them, I have seen, talk wildly of going on to Delhi. Everywhere recruiting is going on and there is much excitement at the success of the Moslems.’

71