In the Break (20 page)

Authors: Jack Lopez

In another scenario my father accompanied me back to La Isla de los Delfíns. He believed me about the island. And when we

returned, the dolphins were still there, and Jamie’s board was on the beach, and I surfed in that bay while my father watched,

and I swore that Jamie’s presence was there, swore that I could see him in the waves with me, tucked back inside the tube,

dolphin-kicking.

I also tried to remember accurately what happened, another suggestion from the psychiatrist. But it was hard to be truthful.

Here were the facts: the image of Jamie freefalling down that horrendous wave will be in my psyche forever. I didn’t remember

much of that day after the outside reef broke. Amber pulled me from the surf, barely conscious, vomiting and shivering. She

claimed a dolphin had swum me in to shallow water. I remembered nothing of that. When I came around, no matter how hard or

where we searched, we found nothing of Jamie or his board. Jamie was drowned; Amber was married; I was on probation.

The psychiatrist also told my parents that it wasn’t right that I hadn’t cried. At first I thought I might tear up over any

little thing, and then when I refused to believe that Jamie was gone, it was easy not to cry. Even when I found out that Robert

Bonham and Amber were married, I didn’t cry.

I was supposed to prepare myself mentally to return to school, though all I did was ruminate about the trip, and the surfboards

were a tangible link to that time and place, I supposed. And to make my life go on, it seemed, I cared for the boards. Maybe

that was the starting point. Mine sat in the garage, gleaming its resin shine, though its nose was broken, a perpetual reminder

of my notorious surf trip. Placing Amber’s board in the sun and leaning it against a trash can with the middle fin on a cushion,

I prepared to work on it. The sun was hot and almost immediately it began to melt the wax. My mother had given me one of her

old spatulas, which worked well for removing the wax off a surfboard.

Straddling Amber’s board, I took the spatula and with the edge worked down from the nose to the tail. A big gob of wax formed

on the spatula. I flicked it off into the dirt by the trash cans. After two passes straddling the board, I could work on one

side, which I did, removing the wax. There were a bunch of shatters on her board’s blue edges, I noticed, as the disappearing

wax revealed what was truly underneath. Her stringer was fine, though; no water taken in. Another time I will seal the shatters,

along with all the ones on my board. The shatters were from hitting the beach. The boards were all I had left, and it seemed

as if the events from the recent past

were truly only a dream. After I seal the shatters I’ll polish both boards. Something to do since I didn’t surf anymore.

I cleaned the spatula with a cloth. Then went over the entire surface of the board, removing any wax spots that I hadn’t gotten.

As I worked over the board sweat dripped onto the deck. The hot May sun burned my back and neck, but I didn’t care. I just

went over and over the deck’s surface, as if removing every speck of wax could somehow right things. After a number of passes

with the spatula, I wiped down the entire surface of the board, top and bottom. Then I got out the acetone and continued to

rub the fiberglass surface. The sweet smell of the acetone coupled with the afternoon heat and the fact that I hadn’t eaten

all day made me woozy. But, still, I kept my arms moving.

Oftentimes I was aware of Amber’s presence. I felt her holding me in the warm sand with the water’s explosions going off all

around us. And sometimes I awakened in the night, thinking that she and I were lying together, but we weren’t. Sometimes when

I closed my eyes I saw Jamie taking that endless drop, weightless; saw him falling, falling down the face of that humongous

wave, his feet firmly planted on the deck of his board, even though his board was not

in

water as that massive barrel overtook him. I saw him take the drop. I saw the white universe approaching me. When I relaxed

and didn’t focus and let the images flow through my mind, sometimes I felt the presence of dolphins, as Amber said. But it

was nothing definite.

I took Amber’s board into the garage, placing it on top of mine and covering it with an old blanket. Then I went over to the

block wall and climbed on top of it, looking at the ocean. The swell was

building, and I saw the steady lines of whitewater at the beach. The first south swell of the season, the first of the water

from the southern hemisphere.

Much of the time I was scared, and especially now, as I would be going back to school tomorrow. I didn’t know how the other

kids would treat me. I wouldn’t have my best friend with me, and Amber wouldn’t be around. I did know this: nothing would

ever be the same again. I was responsible for Jamie’s drowning. If I hadn’t taken my mother’s car …

But I had already been taught the greatest lesson of them all: loss. The loss of my best friend; the loss of the girl I loved.

The psychiatrist said that I must accept Jamie’s death, and that I must accept the fact that Amber was gone; I had.

As I turned to leave the wall after having looked at the waves, Nestor and my mother were suddenly there. Bonnie had gone

into labor, and my parents had been at the hospital with Raul. “You’re an uncle,” my mother said.

I smiled. “What’s his name?” We’d known the sex of the baby.

“James,” Nestor said. Bonnie’s father’s name.

I looked up into the blue afternoon sky, seeing a few streamer clouds scudding along, hearing seagulls squawking down at the

beach, smelling the salt air chugging in over the mesa, and I didn’t know what gave because suddenly Nestor was holding me,

squeezing me tightly, and my whole body was shaking and my face was wet and I couldn’t stop sobbing, just like some damn baby.

“There, mi’jo,” he said, and I felt his strong embrace cover me like a tube.

I’m bored already at school, as usual, even though I haven’t been here, like, since forever. Mr. Vance, my tenth-grade English

teacher, is droning on about Dickens and Pip. He embarrassed me earlier when he welcomed me back. He was all worked up, his

face red, and spittle flying all over the front of the room. He was saying stuff like, “You guys have to face your challenges.

There are no obstacles, only possibilities. Everybody makes mistakes. It’s what we do with our knowledge of those mistakes

that counts.” Crap like that, which made everyone in my class squirm, not just me. And using me as an example! Saying that

I surfed and I was going to college (we’ll see about that, if I can salvage this year) and I was Latino to boot! That’s what

I get for always getting A’s in English. What I get for being in the H classes.

Now, thank God, he’s simply boring.

Susan Cohen rolls her eyes at me and Sylvia Cisneros touches my arm as she walks by my desk when the bell rings. Mr. Vance

calls to me, but I pretend not to hear him and keep walking. Homeroom is over.

In the halls nobody seems too concerned that I’m back, though Greg J., the surf team god, goes out of his way to acknowledge

me. Some of my school friends ask “what’s up?” as they pass, like I haven’t been gone forever. I sit alone in the back of

my next class, history, while Ms. Scanlen goes on and on about some revolution. The room’s door across the hall is open, and

Herbie French sits there, bored stiff too. I flip him off every time Ms. Scanlen isn’t looking. I have to focus my attention

toward the front of the room, flipping off Herbie “blind.” When Ms. Scanlen looks at the class, I can turn my gaze at Herbie,

who in turn flips me off when his teacher, Mr. Evans, isn’t looking. When I last flip off Herbie and look over at him, who’s

standing there but Mr. Evans, one of a few black teachers at our school. He shakes his head and closes the door on me. I flipped

off Mr. Evans! And I can see Herbie with his head on the desk, stifling his laughter. Mr. Evans is cool; Ms. Scanlen is a

boor.

And so the day progresses in a somewhat usual way. Except that Jamie isn’t here.

When school’s over I walk down to the pier. Greg Scott and Herbie and some other guys I know are in the water. I haven’t been

out in so long and it feels weird to watch my friends surf from up on the pier, a thing that only tourists do.

I thought a lot about surfing when I was stuck at home, and I wonder if Amber surfs anymore. I don’t think there are waves

in Oklahoma, but you never know these days. When I thought about when I would get back in the water I’d wonder, Why will I

get a second

chance, a second surfing life? Jamie doesn’t surf. Or maybe he’s perpetually surfing. Maybe time stops when you die; maybe

it’s like the moment when entering wavetime and everything’s frozen, maybe that’s what death is and Jamie is forever in that

place on that wave. That would be heaven for Jamie, to be in the prime moment, the second that everything and nothing are

the same. That’s where Jamie is: taking the drop on a wave on an island.

As I daydream, watching the water move through the pier, I hear Greg Scott yell, “Come on out, Juan!”

The waves are decent, about four feet on the sets, looking fun. And there is some power to them, the swell generated far down

in the southern hemisphere, traveling across the seas, hitting our shore.

“No board!” I shout down to him.

“You can use mine. C’mon, get in the water.”

“Can’t. I’m not supposed to.”

“Shit,” Herbie yells, as if what we’re supposed to do and what we actually do have any connection. He takes off on a cool

little three-foot line, working it all the way until it peters out next to the pilings.

Greg Scott rides in, waving me down to the beach, once he’s on it.

“I don’t even have a wetsuit, dude,” I say.

“Look.” He points down to the pile of stuff, backpacks and towels and who knows what, and there’s a wetsuit. “Ricky was here

but he split. He won’t care.”

And so with Ricky Ybarra’s wetsuit and Greg Scott’s board, I paddle out, even though I’m still technically grounded. But Nestor

is softening toward me, I know by what happened yesterday. I paddle close to the pier, and I can hear the waves’ soft echo

as they stream through the pilings. I can hear guys paddling, the slap of their hands on the ocean’s surface as they take

off, can hear the rush of water as the waves fold over themselves, and I can feel the warm sun on my back and the refreshing

cool of the sea as it passes over me on the paddle out. Off in the distance I can see pelicans and gulls fishing. Three dolphins

break the surface out beyond the surf line, heading south, blowing air out their blowholes as they arch back down into the

water.

As I get into the lineup, and with the image of the dolphins still in my mind’s eye, I take off on the first wave of a set.

My friends let me have it — in fact they seem happy that I am out. I stroke for all I’m worth, heading toward shore as the

wave tries to beat me, but it doesn’t, I catch it, and as it starts to feather over, I stand up, and I’m weightless… .

Special thanks to Alvina Ling for her patience, kindness, and gracious suggestions for editing this book. Thanks to Ricardo

Means Ybarra and Sean Carswell for their insightful reads of the manuscripts, their knowledge of surfing, and their friendship.

And, as always, thanks to Pat, my

first

reader

.

- We’ve all made bad decisions. What’s the worst decision you’ve ever made? What were the consequences for you? Did your decision

affect anyone else? - Have you ever experienced violence firsthand? What did you do? How did you feel after?

- There’s a cliché that goes: Things can change in the blink of an eye. What sudden changes does Juan experience? Have you found

yourself in similar situations? - Another saying goes: “We’re born into our families, but we get to choose our friends.” What do Juan and his friends all have

in common? Do you have friends who share similar interests? How do you choose your friends? - Juan’s family background is different from that of his friends. How does he deal with this? Is it important to him? Have you

been in a similar situation? - Oftentimes in literature, people from racial groups are portrayed in a certain way. Juan, a teenaged California surfer, is

Latino/Chicano. Does his character deviate from other Latino/Chicano characters you’ve read about? If you feel the answer

is yes, in what ways does he differ? Have you ever gone against the “norm” of what is expected from your racial group or gender? - The book begins with Juan surfing with his friends and it ends in the same place in the same way. How has Juan changed in

the ensuing time? - In literature an

epiphany

occurs when a character has a revelation while looking at something ordinary; the character figures out something that he

or she previously hadn’t known, or sees something in a new way. When does Juan have an epiphany? How does he feel afterward? - A writer sometimes includes in his work references to another book or books. These are called

literary allusions

. Can you find any in this novel?

and friendship

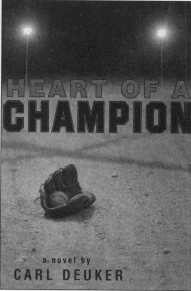

Jimmy Winter is a born star on the baseball field, and Seth Barham can only dream of being as talented. Still, the two baseball

fanatics have the kind of friendship that should last forever. But when Seth experiences an unthinkable loss, he’s forced

to find his own personal strength—on and off the field.