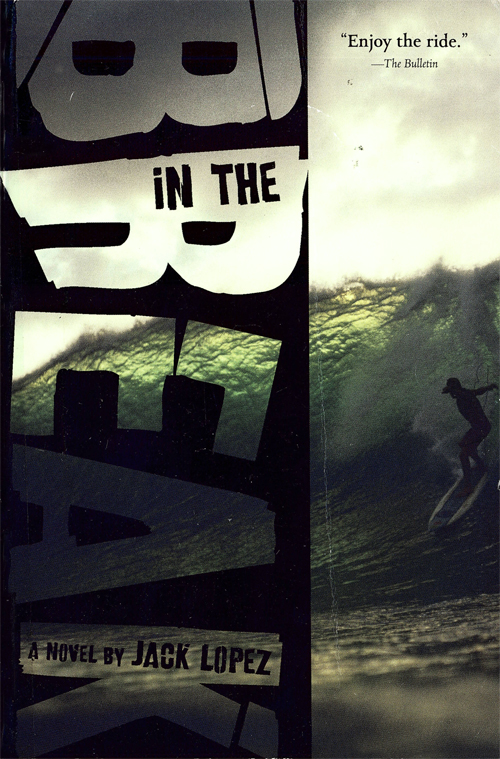

In the Break

Authors: Jack Lopez

Copyright © 2006 by Jack Lopez

Reading Guide Copyright © 2007 by Jack Lopez

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: October 2009

Epigraph quote from

Island of the Blue Dolphins

by Scott O’Dell, 1960, Houghton Mifflin Company.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental

and not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-08557-1

Contents

A story of baseball and friendship

When it comes to the deep blue— it’s the girls that rule!

For my mother,

Agripina Estavillo Lopez

A WAVE

PASSED OVER MY HEAD AND I WENT

DOWN AND DOWN UNTIL

I thought I would never behold the day again.

—Scott O’Dell,

Island of the Blue Dolphins

“Juan.”

No answer.

“Juan.”

No answer.

“What’s with you, Juan?”

I wanted to sleep!

“Psssst! C’mon, swell’s up.” Half whisper, not his normal voice.

“Shut up.”

Normal voice: “Get up, asshole.”

“Okay, okay. Keep it down.” It was Sunday morning, and my mother and father liked to sleep late. Everybody was supposed to

keep quiet, not supposed to have friends come to their windows and shout out for the whole damn house to hear.

“I’ll get your board.”

“Yeah.” I put the pillow over my head and went back to sleep. Then Jamie began honking the horn! I looked at the clock. It

wasn’t even 6:30. I looked at my older brother’s twin bed, empty, unused.

On the way out of the house I saw my little brother already catatonic in front of the TV — anime or something. No, it was

too early for those shows, and, besides, they were on Saturdays. “Paul, tell ’em I went surfing.”

He grunted without looking at me. Twerp seven-year-olds!

I threw my pack in the backseat on top of our boards that Jamie had stuffed in … F’s car? “What are you doing with F’s ride?”

“My mom’s car’s dead.”

I didn’t like this one bit. “Does F know?”

“Screw F,” Jamie said, putting the car in gear and peeling out.

I had to chuckle. F, Jamie’s so-called stepdad, (Frederick was his name, but our nickname for him was Fuckhead and F was what

we called him) was such an ass, he deserved to have his car taken. But the funniest thing was, had Jamie shown up in his mother’s

car, which he usually did, I wouldn’t have thought a thing of it, even though he only had a learner’s permit. He always drove

as if he had a license and his own car. But now, it really did seem illegal, somehow, what we were doing.

I looked over at Jamie. He had the seat way back so he’d be low in it, though his legs were still scrunched at the knees.

His hair was all messed up and blowing in the wind. Even though there was a chill in the early morning air, he had the windows

down.

“What?” he said, and then laughed his high-pitched laugh. It was like a weird hiccup or something.

I shook my head.

“You won’t do that when you see the waves.”

“There aren’t any waves.”

“Greg J.’s getting it right now.”

“No, he’s not. Did they go?”

“You bet they did.”

Greg J.’s father surfed and took Greg J. and his older brother down to Baja. Greg J. was on the surf team, he had a huge expensive

house, and his dad had customized a van for Baja surf trips. I think his grandfather even surfed, dammit! He wasn’t our friend.

A hurricane swell was on the way. But it was too soon for the waves to be here, or so the buoy readings said last night when

I checked them online. “They’re not getting anything this weekend.”

“You gotta believe, Juan.”

“I do. In surfcams.”

We dropped down the hill, turned left on the Coast Highway, passing sandy Playa Chica, heading toward the pier. On the mesa

where we lived you could smell the ocean air, but when you got closer it permeated everything. There would be one more even

stronger blast right before you got in the water. It was funny, I knew where Jamie was headed even though we hadn’t talked

about it. There was a sandbar right in front of Greg Scott’s street. It had built all summer, and now, with the approaching

big swell from the south, it would fire!

When we could see the waves, Jamie said, “Fuck.”

I knew it. “Swell’s going to hit tomorrow. Maybe, if we’re really lucky, a little action this afternoon.” You can get all

the info you need online.

“Tomorrow’s school.” He parked the car; we got our boards and stuff, and walked down the sand to the water’s edge. The surf

was little.

On the paddle out we could see who was in the water (Greg Scott, Ricky Ybarra, Herbie French, a bunch of other guys I didn’t

really know, and some old longboarders), what the tide and the waves were doing (dropping tide, dinky waves), and how the

crowd was (big for so early, soon to get bigger). One good thing about surfing is that the waves almost always seem smaller

from shore than when you enter the water. Sure, these waves were small, but they were hollow from the dropping tide, and would

only get faster.

“Yeah!” Jamie shouted to Greg Scott as he crouched and got covered and then scrunched in the shorebreak. He broke the surface

and looked at Jamie and me. “It’s about time,” he said, jumping on his board. As Greg Scott paddled, Jamie caught up to him,

tugged on his leash and kept pulling, and passed him by pushing off his body. Greg Scott hadn’t been expecting this, and I

too caught up to him and propelled myself by grabbing on to him and thrusting myself forward, paddling hard to catch Jamie.

“Pricks!” he shouted as he got hit by an incoming wave.

We paddled out to the sandbar ahead of Greg Scott, scoping out the lineup. Boom — in no time some little lines showed, and

Jamie caught the first one, acing out some older guy who’d been there first but didn’t have position on Jamie. The guy whistled

his disapproval. Jamie looked back just before dropping in, staring at the guy.

That was the problem with surfing around older guys: they thought that just because they were older, you were supposed to

cut them some slack. On the next wave I out-positioned the dude, and he really whistled. After my ride and on my way back

out I saw the same guy go ballistic when Herbie shoulder-hopped him. Who gave a shit, we were surfing!

Paddling back out yet again, I watched Jamie take off, stalling his board at the top. When he shot down the line and some

guy dropped in on him I tensed, though the kook flopped off his board. Jamie was still in a good mood. Had the kook pissed

him off and been older, Jamie might have thrown down with him in the shallow water. By the time the whitewater from that wave

got to me, I pushed through the measly remnants.

It had remained a clear, calm morning, unusually warm even for late September, and particularly crowded, though it was what

you’d expect for a Sunday. I was tired but took off anyway on the next wave: waist-high mush. I faded left, cranked a turn

when I hit the bottom, going right. There was no juice to it, so I turned back into the whitewater, bellying the pathetic

thing all the way into shore. I picked up my board and walked through the swirling water up the incline onto the white sand,

where Amber, Jamie’s sister, sat with Robert Bonham. The sea was now riffled with the rising wind, and

Jamie was paddling back out to the lineup, toward our friends. I placed my board on Amber’s.

Turning back and facing the sea, I scanned north toward the bluffs and then all the way south to the pier. There wasn’t much

of a swell. The tide was coming up as was the crowd, making the surfing day over. Whitewater hit the pier’s pilings with a

gentle regularity, and tourists dotted the top of the structure. I stretched my arms over my head and swiveled side to side.

Then I grabbed my towel and looked at Amber and Robert. Bad vibe. Fighting vibe, which they’d been doing a lot of recently.

Amber sat on her beach towel, looking out to the break, fidgeting with her Hello Kitty backpack, which she always had with

her, it seemed. In it she kept her journal, and shells and beach glass and all kinds of shit that she was always collecting

on the beach, feathers and rings and all sorts of trinkets. Robert stood beside her, looking toward the pier.

Amber was so pigeon-toed that her feet actually crossed over in front of each other as she walked. But they never collided,

though it appeared that they should. Even when she surfed. She never wore shoes in the daytime, only at night. When it was

warm as it was now she surfed in board shorts and a bikini top with a rash guard, which she now wore, sitting on her towel.

She always had a deep copper tan, the result of much thought and patience, of lying on the beach or in the sun for hours,

moving her towel so it would face the right direction, rotating her body so that it tanned evenly, and even going so far as

to lie on her sides an equal amount of time as she lay on her back and stomach. She didn’t speak a lot until she knew you,

and even then she was not particularly talkative. She was tall, long-legged, and strong. She never wore any makeup, and

a lot of girls didn’t, but in her case guys thought she was weird; I think they were afraid of her. She was imposing, regal

in her quiet beauty. She had gotten straight As so far through high school, and was planning on going to Berkeley or Stanford

when she graduated. The only boyfriend she ever had was Robert Bonham, the dirty dog (how I envied him!). From the ninth grade

on she was his girlfriend. He was attending community college. Amber was in the twelfth grade, two grades ahead of Jamie and

me.

Now, as she sat on the beach above the high-tide line, looking uncomfortable and sad, her feet, even while sitting, were pigeon-toed.

“The hell with this,” Robert Bonham said, and stomped off toward the service road at the end of the beach.

“Nice,” I said. Supposedly Robert Bonham had been with another girl, or that’s the story I heard. He and Amber had been going

at it for a few weeks now.

Amber stuck her tongue out and crossed her eyes at me.

Don’t, I thought, it’ll make your eyes crossed permanently, like your feet.

The wind was picking up for real now, and I wrapped the towel around my upper body. Amber’d missed the good waves of the morning,

sitting on the beach and arguing with Robert Bonham. I’d rather surf than argue with a girlfriend.

Jamie continued surfing, even though it was getting really windy. He caught wave after wave, no matter how bumpy the faces

were, trying to perform some tricks: floaters, big cutbacks, getting tiny air when he could, all the things you do when you

surf crummy waves but you yourself are really good.

“Oh crap!” Amber said.

I didn’t turn around, assuming that Robert Bonham was back.

“Where is he?” a stern and angry voice half-shouted.

There stood F in a white shirt and tie, slacks, and hard shoes, right on the sand! In all his imposing size and heft. It wasn’t

that F was really that big, or that he was obese or anything. He just looked big, what with his fat head and his meaty forearms.

He gave the appearance of being larger than he actually was. I looked out to sea, ignoring him.

“I know he’s here, and he took my car,” F said. “He was supposed to mow the lawn!”

“I drove,” Amber said. She had come with Robert, about an hour after Jamie and I had.

“Don’t you lie to me. Don’t!” Other sunbathers and surfers began looking at us.

Amber said nothing. She wrapped her arms around her shoulders, trying unsuccessfully to make herself smaller somehow.

“He didn’t ask permission to use my car! He was supposed to mow the lawn on

Friday

! Get him in. Now!”

I looked at F in all his crew-cut, engineer fury. He was a full dick, but he was scary. Especially when he was pissed off,

which was practically all the time. I only saw him around Jamie, and he seemed perpetually pissed at him. Jamie could do no

right as far as F was concerned. So he would yell at Jamie about the car, and, when you got down to it, he’d been yelling

since shortly after he married Claire, Amber and Jamie’s mother. I suppose F had been auditioning for the family before he

married into it when he pretended to be nice to Jamie, pretended he gave a shit about surfing, or any of the stuff that other

fathers are interested in. I didn’t have

to take his orders, but didn’t want any undue grief to befall Amber, so I walked out toward the surf and began waving to Jamie.