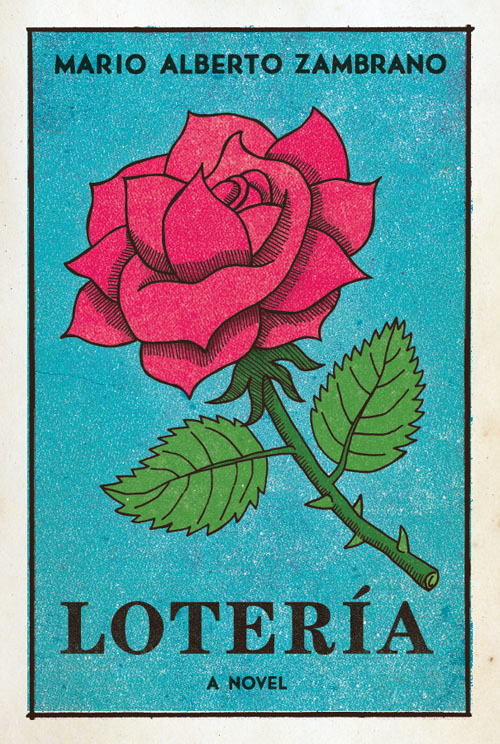

Loteria

Authors: Mario Alberto Zambrano

LOTERÍA

* * * * * *

A Novel

A

t the center of this richly imagined, meticulously constructed, and wondrously atmospheric debut is Luz María Castillo—an eleven-year-old Mexican American in custody of the state. A child withdrawn into herself, she has witnessed and experienced much in her young life.

Now, sitting alone in her room with nothing but a journal and a Lotería deck in front of her, Luz finds solace in looking at the cards, flipping them over one at a time. Each of the cards’ colorful images—a mermaid, a bottle, a spider, a star—inspires a memory, sometimes a meditation, and taken together they become a collage of the tenderness and terror that has filled her life. Here are stories of family and loved ones—of her beautiful and sad mother; of her beloved Papi teaching her to sing

rancheras

; of her sister planning her

Quinceañera

; of leisurely Sundays playing Lotería with her family after mass. These memories begin to coalesce around one night in particular, a night Luz can hardly bear to remember: the night that led her to this lonely place.

Luz is the storyteller-creation of a gifted writer, and

Lotería

marks the emergence of an outstanding new talent.

CONTENTS

L

otería

is often described as Mexican bingo, a game of chance. The only material difference between bingo and

Lotería

is that bingo relies on a grid of numbers while

Lotería

relies on images.

There are fifty-four cards and each comes with a riddle,

un dicho

. There is a traditional set of riddles, but sometimes dealers create their own to trick the players. After the dealer “sings” the riddle the players cover the appropriate spots on their playing boards, their

tablas

, with either bottle caps, dried beans, or loose change.

There is more than one way to win depending on what is played. You can win by filling a vertical line, a horizontal line, a diagonal; the four corners, the center squares, or a blackout.

An important rule to remember is that a winner must shout his victory as soon as his winning image is called. If the dealer calls another riddle before the winner declares

¡Lotería!

, the player can no longer claim his prize.

El que es buen gallo, en cualquier gallinero canta.

T

his room has spiders.

¿Y?

It’s not like You don’t see them. The way they move their legs and carry their backs and creep in the dark when you’re not looking. You see us,

¿verdad?

You see what we see? It’s not like You don’t know what we’re thinking when we lie down at night and look up at the ceiling, or when we crawl in our heads the way these spiders crawl over furniture. It’s never made sense why people think You’re only there at church and nowhere else. Not at home or in the yard or the police station. Or under a bed.

When I first walked in there was a wooden desk and a chair that wobbled when I sat in it, next to a thin bed with a green blanket. Tencha said the room needed something so she started buying me roses from the flower shop in Magnolia Park and putting them on the windowsill. From one day to the next I watch the petals fall to the floor and that’s when I notice the spiders. They crawl to the cracks in the wall when she comes to visit then crawl out again when she leaves. I’m at my desk doing what she told me to do, because she said I should write as much as I can, even if it’s one word, one sentence. Let the cards help you, mama.

Échale ganas

.

My name is Luz. Luz María Castillo. And I’m eleven years old. You’ve known me since before I was born, I’m sure, but I want to start from the beginning. Because who else should I speak to but You?

It’s been five days since I’ve been here and I don’t have anything but a week’s worth of clothes and a deck of

Lotería

. The best thing to do now is to be patient and cooperative, they say, otherwise I’ll be sent to

Casa de Esperanza

. Tencha can’t have custody, not unless we move back to Mexico, and they say that whenever I’m ready to talk it’ll make things easier. But Tencha told them she filed her papers and has been working here for eight years, so why don’t they let me go? Why can’t she take me? I’m waiting for the day she walks in and tells me to pack my bags because we’re going home, wherever that is.

Julia’s a counselor here and looks like she could be in college, skinny and black, but gringa-looking by the things she wears. She tries to talk to me at lunch as she flips her hair to one side like a feathered wing. She brings me issues of

Fama

magazine and points to the photos and asks, “Like her music? She’s pretty, huh?”

Then she looks at me like if I’m one of those stories you hear about on the ten o’clock news. Like one of those women who leave their kids in the car with the windows rolled up while they go grocery shopping. Or a story about some punk kid who molests a girl after school. Or some father who finds out his son’s gay and rams a broomstick up his butt until it bleeds. And whoever reports the story on the news channel has this concerned look over her face standing outside the hospital room where the son’s recovering. She looks into the camera and repeats what the father said to his son as he stood over him with the broomstick in his hand: “You sure you want to be gay, son?”

I’m Papi’s daughter, but still. That story is a true story and that boy was my age and when I saw him on television, I felt bad for him. I wanted to spit in that newscaster’s face, the way she pretended like she cared. To her it was just another story, but to that boy, he must’ve been sore, must’ve been hurting real bad and wondering what it was going to be like once he got home.

There’s a guy named Ricardo staying in one of the rooms on the opposite side of the building. He has dreadlocks that fall to his knees but he twists them the way you wring a mop and plops them on his head. One night we were watching

The Price Is Right

in the common room and he told me he liked to do something called blow. His foster parents found him cutting lines on the kitchen counter and that’s why they turned him in. That’s why he’s getting counseling. He said

Casa de Esperanza

is where they take kids when nobody wants them. After Tencha saw him she told me to stay away from him.

When I’m sitting by myself by the window doodling on paper, Julia comes up to me and tries to act like she’s my best friend. “What are you drawing?” she asks. “I can help you. Why don’t you let me help you?” Then she sits there, staring at me.

¿Y?

It’s not like I’m a piece of news in the

Chronicle

she can pick up and read. It’s not like that. If anything, it’s a

telenovela

with a

ranchera

in the background playing so loud you can’t even hear your thoughts anymore. Like that movie

Nosotros los pobres

, when Pedro Infante is accused of killing his wife. He didn’t do it and only his daughter Chachita believes him. Half the movie is not knowing what happened, whether he killed her or not. Everyone thinks he’s guilty, but he’s not. He’s just poor. Chachita visits him in jail and pleads to the officers to let him go. She has braids in pigtails and throws her arms over her head like Hallelujah! She falls to the floor, crying with tears over her cheeks, all slobbery, all dramatic, like one of those old ladies at church who’s lost her husband, praying,

¿Por qué me haces esto, Señor? ¡Por favor, Dios mio!

Tencha says I should tell Julia whatever she wants to know. If I don’t want to talk then I should write it down because we have to get Papi out of jail. That way we can go home and be together again. The only way he can get out of jail is if I open up, she says.

“Why don’t you use the cards to help you, mama?

Ándale

. Write it down in a journal, like that they can see what happened. Like that they can see he didn’t do anything wrong.”

At first, I didn’t want to. I didn’t feel like it. Besides, Tencha wouldn’t believe me. Or maybe she would. Maybe she knows what it was like but never wanted to believe it in the first place because she loves her brother too much. Either way, I’m keeping this as mine.

What I write is for You and me and no one else.

There’s this spider at the edge of my desk and she’s looking at me like if I’m her

Virgen de Guadalupe

. I don’t want her touching me or getting too close, and I know she’s not poisonous, but still. I could blow her off in one breath if I wanted to. I’m thinking of smashing her, then cleaning her off with my sock and acting like it never happened. But when I raise my hand and close my eyes I hear her scream.

Julia says the reason I don’t say anything is because I’m in deep pain. Like if pain were something she knew looked like me. I hear her when she talks to Tencha outside my room. Because I’m eleven she treats me like some kid. The way she looks at me, feeling sorry for me, scared, but at the same time frustrated. Like if answers are overdue and behind her pity she’s upset that I’m not “cooperating.”

I used to tell You I pray for Your will.

¿Recuerdas?

I used to make the sign of the cross in the dark while I was in bed and tell you how much I loved You. That I wish for the best and I pray for your will. Well, I do, but maybe I’ll smash this spider. Mom used to say that life was full of tests. And if we pass, we’ll be in Your grace. Maybe if she named me

Milagro

instead of

Luz

this would’ve never happened.

If I wait for this spider to crawl out of this room, then maybe I can go after her. And on the other side of this wall there’ll be this underwater world and I’ll swim to the deep end and float next to one of those electrical fish that light up in the dark. And maybe he’ll sting me or split me into pieces or eat me alive. But then everything will be over and no one will remember because I’ll be down there in the dark with nothing around me. With no fish, no light. No Luz.

Then what?