I'm Just Here for the Food (26 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

Filter Your Water

I might be willing to pay three bucks for a latte every now and then, but I just can’t bring myself to pay a buck for a pint of water. I don’t care what glacier it dripped off of or what Alp it perked up out of, I still think it’s a rip-off (see

What’s in Your Bottle

). Luckily, we have water filters.

ACTIVATED CHARCOAL

Activated charcoal is on my “top-ten coolest things in the world” list. Unlike the stuff that you burn in the grill, activated charcoal is a powder made up of tiny carbon sponges. These particles are amazingly porous and can absorb something like a zillion times their weight in organic compounds (including many poisons), as well as a host of nasty chemicals, such as chlorine, solvents, and even some pesticides. How do these tiny grains do the job? For one thing, they are 100 percent carbon, and so they act like Velcro, clinging to any substance containing carbon. More important, they possess an almost unbelievable amount of surface area—up to 160 acres per pound! Think about that a minute. That means that each gram of activated charcoal has in the neighborhood of 14,000 square feet of bonding space. Amazing though this is, all this space will eventually be taken, and the filter will need to be changed. Failing to change an exhausted filter is actually worse than having no filter at all, because the nooks and crannies of activated charcoal are like an ant farm for bacteria. If your water is chlorinated, pathogens shouldn’t be a problem, but the longer that filter sits there, the more you’re just asking for trouble.

There are three types of water filtration systems, all of which utilize activated charcoal (see Activated Charcoal). Since my municipal water is safe and relatively good at cleaning things (see Hard and Soft Water) I don’t feel I really need a high-volume system to scrutinize and scrub every milliliter that comes into the house or even through one particular tap. I’m not a fan of faucet-mounted models because they make every sink they meet look like a refinery and their size necessitates seemingly constant filter changing. I prefer the pitchers with pour-through filters that utilize drop-in filter cartridges. These devices are rather slow but they’re effective and very affordable. Around my house we keep the filter pitcher on the counter and keep a gallon or so (tightly sealed) squirreled away for cooking those designer veggies we were talking about.

If you just can’t bring yourself to spring for a filter (cheapskate), at least take these taste precautions. Let the water run while you count slowly to ten (for better oxygenation) before you fill any vessel. Then bring the water to a boil and keep it there for a solid minute, uncovered, before adding any food (this eliminates some of the chlorine).

FILTRATION UPDATE

They say water is the new oil, so a lot of R&D (that’s research and design) has gone into filtration and purification systems in the last few years. The only ones cooks should really question are RO (or reverse osmosis) systems, which can remove even the smallest spores and viruses from water. The problem is that they waste a lot of water and they remove just about all the mineral content that gives H

2

O any life.

Poaching

Poaching is defined as cooking food gently in liquid that has been heated until the surface just begins to quiver.

I personally have never seen water “quiver,” but since no bubbles are mentioned I assume that we’re talking about a temperature that’s below a simmer. How much below? Who knows? Some cooks argue 180° F—others 185° F—either of which is nearly impossible to maintain on a standard home stove top. Then, of course, there’s the food.

Fish, eggs, and chicken breasts are traditional poaching fodder because they profit from gentle (there’s that word again) heat. The other side of the coin is that these foods get nasty soon after they exceed their relatively low ideal temps—140° F to 150° F in the case of fish and 165° F for chicken meat. So let’s say you’ve got a flavorful liquid (see The Liquid) and you bring it to 180° F and slide in a piece of sole. So far so good, you think, but how do you know when it’s done? It’s too thin to use a thermometer and it’s impossible to time. You’re left there to poke, ponder and pray that you’ll recognize the moment when your dinner enters the narrow (10°) doneness zone, at which point you’ll have to act quickly because the food will be well on its way to a state of thermal equilibrium with its surrounding environment, which is not a happy place for these kinds of foods to be in. So, not only can’t you tell when the food is done, it won’t stay that way for long. No wonder nobody poaches anymore.

The solution?

As much as I’d love to claim this method as my own, I have to give credit to the patron saint of modern food scientists, Harold McGee, who wrote about this method in

The Curious Cook

.

1. Start with the liquid at a boil to kill any surface bacteria.

2. Drop the temperature of the liquid to the final desired temperature of the meat.

This way the food never overcooks. This doesn’t mean you can leave the food in there all night, but—while its never a good idea to turn your back to a simmering pot—you could. Fruit, by the way, is often poached in syrup, but in that case the real goal is not to control the final internal temperature but to cook the fruit without blowing it to bits with the turbulence of boiling.

I like to poach in an

electric skillet

, which I calibrate by filling with water, dropping in the probe of one of my many thermometers, and taking the thermostat for a ride. I found that the temperature range was way off, so I re-marked it with white tape and a pen. Then I went one geeky step further by wiring a dimmer into the cord so that I could maintain temperatures well below the “simmer” level. Of course, I’d never suggest you resort to such extreme measures for poaching, but hey, if you’re handy with wiring, you can give it a try as long as you hold me and my publisher blameless for any potential damages.

The Liquid

I usually poach fish in either wine (I tend toward sweeter wines like Rieslings) or a mixture of wine and water with lemon juice and a pinch of salt. Adding herbs makes the room smell nice, but considering the relatively short cooking time I don’t think it does much for the flavor of the fish—unless, of course, you’re making sauce. One of the nicest things about poaching liquid is that as long as you have added the salt with a light hand, once the food comes out you can jack up the heat and reduce the liquid, mount it and serve it with the fish.

To “mount” a sauce is to stir or whisk in a few bits of cold butter at the last minute.

Master Profile: Poaching

Heat type:

wet

Mode of transmission:

90:10 percent ratio conduction to convection

Rate of transmission:

slow

Common transmitters:

any liquid

Temperature range:

low and narrow 140-170° F (depending on who you ask)

Target food characteristics:

• tender proteins: fish, eggs, chicken and other poultry

23

Non-culinary application:

Jacuzzi on “stun”

Poached Chicken Methods

Combine the wine, stock, bay leaves, and peppercorns in a large heavy-bottomed pot, then proceed with one of the following methods.

Method 1

Place the probe end of thermometer in the liquid and place over medium-high heat to maintain a temperature of 185° F. Submerge the bird in the liquid and set the thermometer alarm for 190° F. If the alarm sounds, the water has gotten too hot, reduce the heat to maintain 185° F. This method takes about 1 hour and 10 minutes. Remove the chicken to a rack set on a baking sheet to drain.

Method 2

Cut the bird into serving-size pieces and submerge in cool liquid in an electric skillet set for 180° F. Use your thermometer in a leg or thigh, and when it reaches 180° F remove pieces to a rack set on a baking sheet to drain. This is probably the most foolproof method.

Now that you have all this poached chicken, what do you do with it? Well, you could simply eat it chilled atop a nice salad of mixed greens and fresh tomatoes with a boiled egg. Or eat it warm with

Hollandaise Takes a Holiday

, chop it into your favorite chicken salad recipe, or even simmer the pulled meat in your favorite barbecue sauce for delicious sandwiches. The possibilities are limitless.

Software:

1 quart white wine

Chicken stock (or water) to cover

2 bay leaves

½ tablespoon peppercorns

1 whole broiler-size chicken

Hardware:

Heavy-bottomed pot (or electric

skillet) large enough to fit

the whole chicken

Probe thermometer

Tongs

Rack

Baking sheet

Simmering

Master Profile: Simmering

Heat type:

wet

Mode of transmission:

80:20 percent ratio of conduction to convection

Rate of transmission:

moderate to high

Common transmitters:

any liquid

Temperature range:

narrow 175-200° F (depending on who you ask)

Target food characteristics:

• Dehydrated starches: rice, dry beans, oats, barley

• Hearty greens: collards

• Foods that can stand up to high heat and some physical convection

Non-culinary application:

Jacuzzi on “kill”

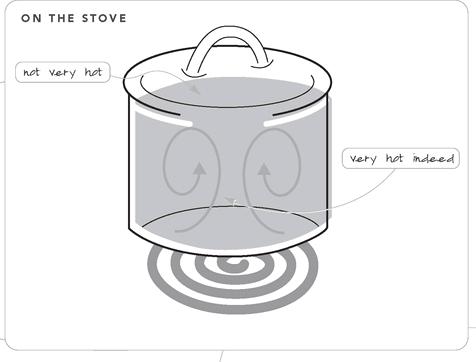

Time and sub-boiling temperatures are the Lerner and Loewe of the kitchen world, a team capable of converting simple culinary notes into remarkable opuses (or is that opi?). Unfortunately, two factors conspire to prevent the cook from hearing the music: dropping below the visual benchmark boil is like flying on instruments; there’s not much to see and what there is can rarely be trusted. Also, the sub-boil lexicon is a nomenclatural netherworld where terms like simmer, poach, braise, coddle, stew and scald create connotative chaos. Consider the most oft-mentioned cooking term in the English culinary lexicon: simmer. There are two common definitions:

1. To heat water (or a water-type liquid) to about 195° F or until tiny bubbles form on the bottom of the pan then travel to the surface.

2. To cook foods gently in a liquid held at the temperature mentioned above.

Already we’ve got problems. First there’s this word “about.” The reason so many cookbooks use “about” is that nobody seems to be able to pin simmering (or any sub-boil technique) down to a single temperature.

Then there’s the trouble with bubbles. The temperature at which water will produce “tiny” bubbles depends a lot on the pot, the weather, even the water itself (See

Boiling in the Microwave

). And what if there’s more in the water than just water? Salt, starch, dissolved meat proteins (maybe oatmeal) can elevate the actual boiling point of the liquid. As stew liquid thickens, its sheer viscosity can impede bubble production. And yet how many stew recipes have you read that refer to those Don Ho bubbles?

Finally, there’s the word “gentle.” Since simmering liquid lacks the physical turbulence of boiling water, it is physically gentle. (Anyone who’s canoed down a river knows that white water will beat you up a lot quicker than flat water.) But when it comes to heat, there are only a few degrees difference between a simmer and a full rolling boil. A “simmer” may not tear your fish to shreds, but it will squeeze the life out of it lickety-split, which is why you should never turn your back on a simmering pot.