I'm Just Here for the Food (25 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

Software:

3 tablespoons peanut oil

3 ounces (about ½ cup) popcorn

½ teaspoon salt (see

Note

)

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

Hardware:

6-quart metal mixing bowl with

sloping sides

Heavy-duty aluminum foil

Kitchen knife

Tongs

Swiss Chard with Garlic and Tomato

If you haven’t made chard welcome at your table, you might want to do so. It tastes like a slightly bitter, slightly salty version of beet greens and it’s packed to the gills with goodness, especially vitamins K, A, C, and magnesium, iron, and potassium. It’s a super-food, all right, and this dish is designed to get more of it into you.

Application: Sautéing

Blend the butter and flour in a small bowl until a smooth paste is formed.

Heat the olive oil in the sauté pan over medium heat. Add the onion, garlic, and red pepper flakes, and sauté until the onions turn golden, about 7 to 10 minutes.

Drop the heat to medium-low, whisk in the flour and butter mixture and cook for 5 minutes.

Next, introduce the tomatoes to the party and keep whisking for 2 to 3 minutes. Add the chicken stock and whisk until the sauce is smooth and creamy. Add the cooked pasta and the chard and stir until heated through.

Finish with the Parmesan and rosemary. Taste and season with salt and freshly ground black pepper to your heart’s content.

Yield: 6 servings

Software:

2 tablespoons butter, softened

2 tablespoons flour

2 tablespoons olive oil

½ cup diced onion

8 cloves garlic, thinly sliced

¼ teaspoon red pepper flakes

2 cups canned crushed tomatoes

1 cup chicken stock

16 ounces dry bowtie pasta, cooked

1 bunch Swiss chard, trimmed,

blanched, and chopped

½ cup grated Parmesan cheese

1 teaspoon fresh rosemary,

chopped fine

Kosher salt

Freshly ground black pepper

Hardware:

Cutting board

Chef’s knife

Can opener

8-quart pot for blanching chard

6-quart pot for pasta

Colander

Small mixing bowl

Whisk

12-inch sauté pan

Cheese grater

CHAPTER 5

Boiling

Boiling . . . sure, you know it when you see it, but do you really know it?

Water Works

Dictionaries may define cooking as the application of heat to food, but there have been plenty of food thinkers through the ages who have postulated that cooking has less to do with heat than it does with water management. After all, there is no food that doesn’t contain water and the changes that take place in food during cooking can largely be quantified by what happens to the water in question. Water is not only our most common cooking environment, it is the only one that can act as a heat conduit and a solvent at the same time, which is especially important in the making of stock.

The stuff is everywhere and yet science has yet to get a good grip on water. You, as a cook, must get your head into water before you can get it around cooking.

What Is This Stuff, Anyway?

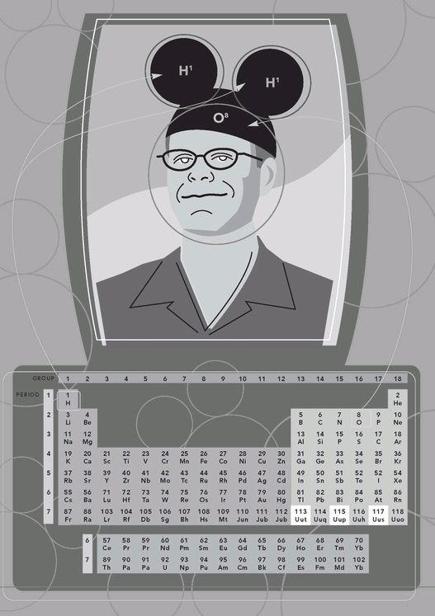

Begin by putting on a Mickey Mouse hat. Now stand in front of a mirror and take a serious look at yourself. Yes, you do look silly but you also look like a molecule of water—your head representing an oxygen atom and each ear a hydrogen atom. Each of these elements has a long and interesting career (being flammable helps), but what makes them particularly interesting here is how they’re joined.

The reason the hydrogen atoms are attached Mickey Mouse-style to the oxygen has to do with oxygen’s attraction to hydrogen’s electrons. It pulls on their orbits so strongly that the hydrogens list to one side, resulting in an asymmetrical and electrically polar molecule. If oxygen weren’t so greedy for electrons, your hydrogen ears would connect at 180 degrees (think Princess Leia). Of course, if that were the case water would boil at about 150° F; you wouldn’t need a hat, because you wouldn’t exist—nor would any other living thing. In short, the curious triangular configuration of the water molecule makes life (and cooking) on earth possible.

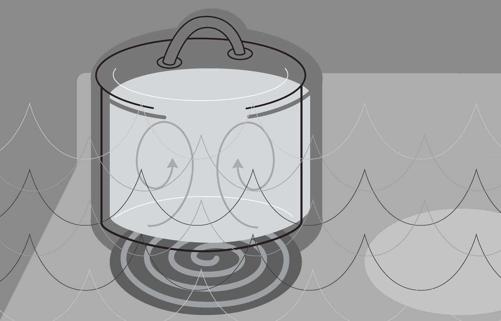

In its solid state, water’s molecules are ordered and equally spaced, as if taking part in a very slow line dance. As it warms up, the bonds that hold it in this rigid but open pattern release, and you’ve got something like a disco on your hands. Now the molecules are packed tightly together and every atom on each molecule is free to hook up with other atoms on other molecules via hydrogen bonds. At any given time, dozens of water molecules can be loosely bound together in a molecular group hug. A food item placed in this environment is going to come in contact with a lot of water molecules and will conduct heat from them while getting physically tossed around a bit.

WHAT’S IN YOUR BOTTLE?

Ever responsive to human needs, marketing mavens have made it possible for every American to pay a buck for a pint of water. Waterheads not only proclaim their favorite brands but their own ability to discern the differences between glacial water and mineral water.

This is not to say that the flavor of water doesn’t matter; it does. I’m just not ready to have a waiter hand me a water list along with my menu.

The government, in its wisdom, recognizes and enforces the following designations.

Aquifer (a large, naturally occurring underground cistern). Drill into it, and pump or lift the water out. That’s well water.

Aquifers often run with the strata of the land as they dip and curve and are perfect for an artesian well. If you drill into an aquifer at a particularly low point, the majority of the water will actually rest above the level of the well itself, so its own weight pushes the water out of the well. The only difference between a spring and an artesian well is that spring water finds its way to the surface unaided.

Spring water must come to the surface under its own power. It can be drilled for, but only if the resulting supply is chemically identical to the natural flow. It can even be pumped from the ground, but only if the original spring continues to flow.

Bottled water that contains at least 250 parts per million total dissolved solids can be called mineral water. Said minerals include calcium, magnesium, and sodium. Since it does contain minerals, mineral waters do possess actual flavors, even if they’re unflavored by man.

WATER CONVERSION

Because of water’s fondness for hydrogen bonding, it can absorb a lot of energy (in the form of heat) without actually changing temperature. This explains why even twenty-first-century cars have radiators, elephants have big ears, and human beings sweat. In the case of the latter, moisture carries heat from the inner core of our bodies to the outside, where it evaporates. The conversion from liquid to vapor absorbs even more energy and we cool off. This also explains why a bottle of beer chills faster in a bucket of cold water than in the relatively dry air of the freezer.

Distilled water is pure H

2

O. Everything else has been removed by either reverse osmosis or carbon filtering. Since no trace of anything else remains, distilled water tastes freakishly flat, but it is good for cleaning lab equipment and filling irons. Some water bottlers use it as an ingredient for “making” mineral water.

Natural sparkling water is naturally carbonated spring water or spring water that has gone flat and has been recarbonated to the exact level of carbonation it had before it wasn’t flat . . . if that makes any sense.

Club soda, seltzer, and soda water are classified as soft drinks, not bottled waters, because they are essentially tap water that’s been manipulated by man. In most cases sodium bicarbonate has been added along with other flavorings (quinine in the case of tonic water) and salts. Since it contains soda, these waters are often used in baking and in certain batters, such as tempura. If you have a recipe that calls for club soda or soda water, do not replace it with naturally sparkling mineral water or you’ll be sorry.

Now, say you go into a store and pick up a bottle of water that bears a three-color graphic of crystal-clear water gushing from a pristine mountain crag. Looks good, right? Okay, now look for the words “purified water” or simply “drinking water.” Find them? That water came from a municipal source—the tap—and has been purified and possibly fortified with minerals. So skip the pictures and go for the small type. “Glacial water” must by law come from a glacier. “Naturally sparkling” water must come straight from a spring, with bubbles.

HARD AND SOFT WATER

Hard water happens when water absorbs CO

2

(thus becoming acidic like acid rain), then comes in contact with limestone or rocks or soil containing calcium, magnesium salts, bicarbonates, chlorides, and the like. Since it’s a great solvent, the acidic water dissolves and absorbs large amounts of these solids. They remain in the solution until the water is either heated (in your hot water heater or tea kettle) or has its pressure rapidly reduced (your kitchen faucet or dishwasher sprayers). Then they become rocklike deposits that stick readily to things we don’t want them to stick to. Hard water is also terrible at washing things. That’s because it’s already got its molecular mitts full of minerals and can’t get a grip on soap or dirt.

Soft water is the opposite of hard water. It’s relatively free of dissolved solids so it’s a great solvent and soap’s best friend. However, when it come to drinking or cooking water there is such a thing as too soft. Very soft water is flat tasting (like distilled water) and since it lacks minerals, not as good for you as harder water. Super-soft water also tends to brew lackluster coffee, tea, and beer.

As more heat is added, the action on the dance floor gets frantic. Add enough heat, and the water will eventually come to a boil. Hydrogen bonds break down, the atmospheric pressure holding the water in the pot will be overcome, and the liquid will begin to move into the vapor state we call steam. When that happens, the water expands radically, like disco dancers who suddenly decide to break into a Viennese waltz. Food placed in this environment may not bump into many molecules, but those that are encountered contain considerable energy. While this is bad news, for say, your hand, it’s good news for delicate foods that would otherwise be torn to shreds in the boiling water discotheque.

Since most of us can open up a tap and take as much of the planet’s water as we want, we tend to think of water as a constant rather than an ingredient. I’ve seen cooks spend all morning at the farmers’ market, hand picking the finest designer-organic-heirloom vegetables, only to chuck them straight into a pot of tap water that smells like the kiddie pool at the Y. If your municipal

agua

leaves something to be desired, you should either filter it or give up and start from scratch. (If you’re curious about what’s coming out of your taps, request a water quality report from your local water company.)